[ad_1]

Researchers have announced the discovery of bone tools in a cave in Morocco that appear to have been used to carefully remove skin and fur from the bodies of dead animals. The skins thus recovered were apparently used to make clothes.

Such a discovery would normally not be considered remarkable. But these particular tools are around 120,000 years old, pushing the calendar of garment-making practices further into the past than scientists might have thought possible.

“These bone tools have shaping and use marks which indicate that they were used to scrape hides to make leather and to scrape hides to make fur,” explained the anthropologist and research team leader, Dr. Emily Hallett, in a press release from science journal publisher Cell Press.

“At the same time, I found a pattern of cut marks on the bones of carnivores in the Smugglers Cave which suggested that humans did not process carnivores for meat but rather skin them for their fur.”

The ancient makers of fur and leather were the first Homo Sapiens (modern humans), who at this point had not yet left Africa to explore and colonize the rest of the planet. Even before the original great migration that dispersed their populations across the world, early humans exhibited a surprisingly sophisticated range of behaviors.

“Our study adds another element to the long list of characteristic human behaviors that began to appear in the archaeological records of Africa around 100,000 years ago,” said Dr Hallett, who, with most of the scientists involved in this research project, is affiliated with the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany.

The site of the Smugglers’ Cave, Morocco ( The Guardian )

Researchers do not expect to find actual samples of clothing during the smuggling cave excavation. Leather and fur clothing is said to be too delicate to be stored for over 100,000 years.

But fascinating studies of the DNA of clothing lice have shown that they likely evolved from human head lice between 83,000 and 170,000 years ago. This dates back to the days when modern humans still lived exclusively in Africa, providing further evidence that people have been making clothes for a very long time.

Tools tell the story

As they explain in an article detailing their findings in the journal iScience, Dr Hallett and his colleagues took a close look at the remains of animal bones excavated over several decades in the Smugglers Cave on Morocco’s Atlantic coast. These bones had been unearthed in layers dating back to between 120,000 and 90,000 BC.

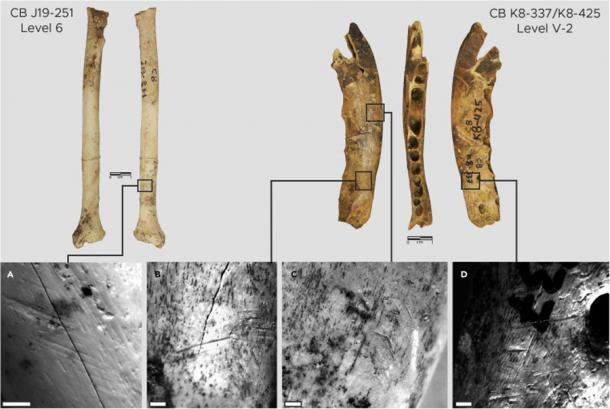

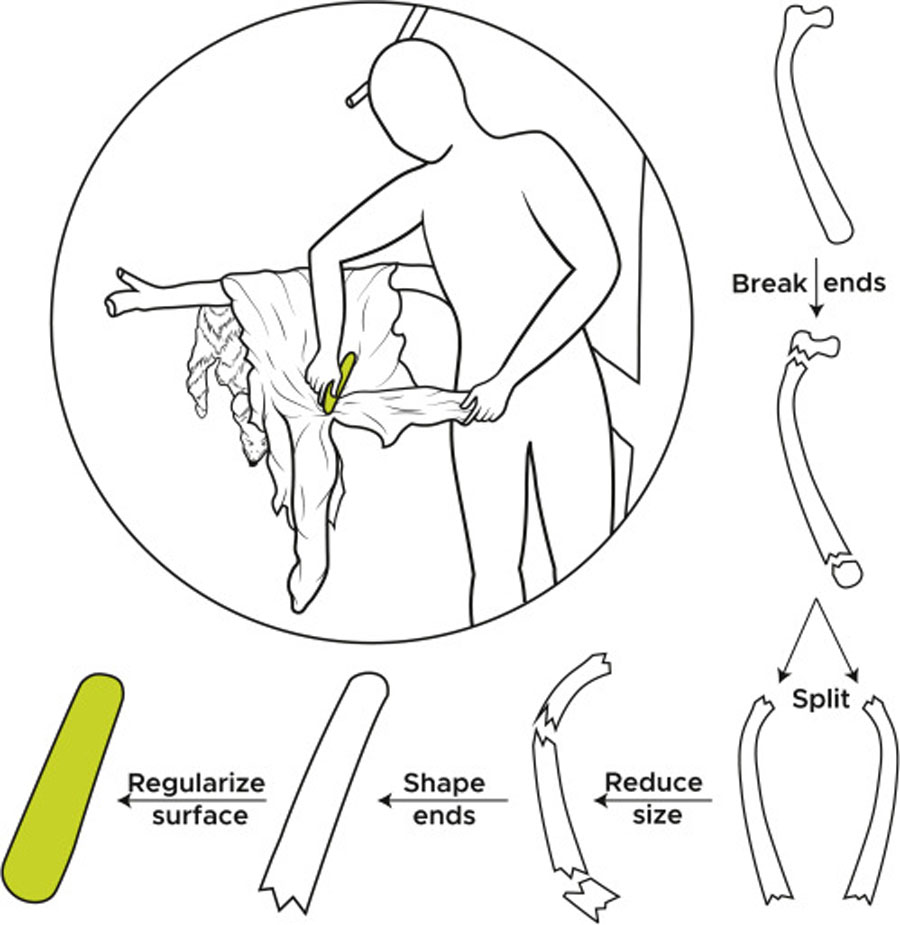

Some of the animal bones (62 to be exact) had obviously been fashioned into tools of various kinds, and one type of tool in particular caught their attention. These sturdy objects were made from cattle rib bones and had been rounded into a spatula shape at one end.

“Spatula-shaped tools are ideal for scraping and thus removing internal connective tissue from leathers and skins during the skin or fur working process, as they do not puncture the skin or skin,” wrote the researchers in their article iScience.

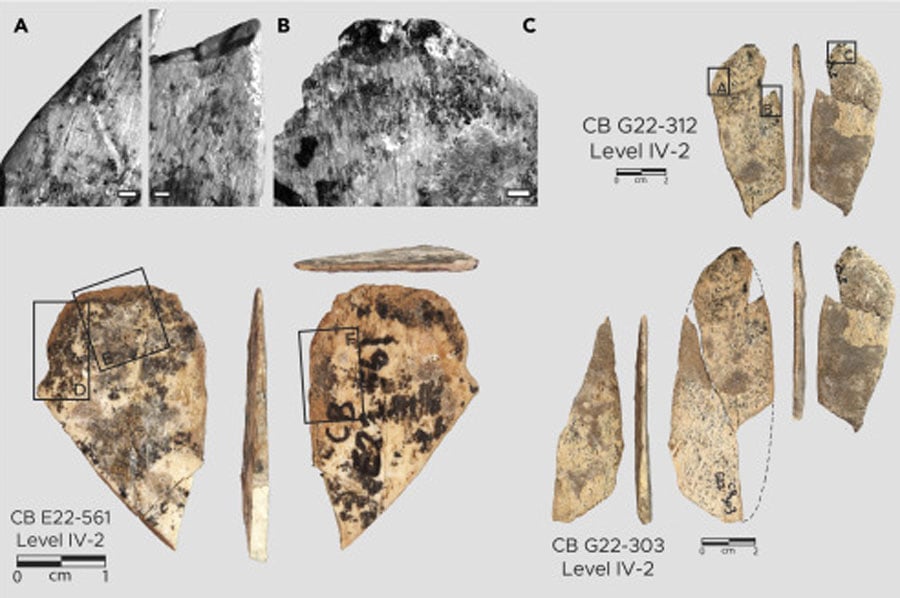

Skinned fox bones with scratch marks ( Cell press )

Some of the bones examined by Dr Hallett and his colleagues had not been turned into tools at all. But they did contain telltale scratch marks showing that the attached skin and fur had been carefully and carefully removed. It is noteworthy that the bones that contained such markings were from species that would likely have possessed thick fur coats, including ancient versions of foxes, feral cats, and jackals.

Dr Hallett found other marked bones from species similar to modern cattle. But in these cases the cuts and scrapings had different characteristics. These marks were of a type that would occur if the meat were boneless, for use as food.

Another intriguing find found in the cave was a whale tooth, which had been partially altered and was probably used to scale stone. Dating from the same period of 120,000 to 90,000 BC. Nothing like this at any time had ever been found in North Africa before, confirmed Dr Hallett.

Prehistoric humans did, and Neanderthals did too

Dr. Hallett doesn’t think modern humans were the only hominid species to discover the benefits of clothing. She believes that European Neanderthals made clothing from animal skins and furs before modern humans arrived in the region, possibly around 40,000 years ago.

Evidence is available that supports this theory. In 2013, archaeologists discovered a special type of leatherworking tool known as a smoother during excavations in two caves (Abri Peyrony and Pech-de-l’Azé) in southwestern France. These caves were once occupied by Neanderthals rather than humans, and the tools in question were apparently made around 50,000 BC.

Commenting on the latest findings in Morocco, Dr Matt Pope, an archaeologist at University College London, told the Guardian that these ancient humans must be accomplished leatherworkers.

“It’s an adaptation that goes beyond just adopting clothes,” he said. “This allows us to imagine clothes that are more waterproof, more fitted and easier to put on than simple scratched skins.

How the tools were shaped and used ( Cell press )

Dr Pope noted that the well-processed leather could also have been used to make containers, windbreaks, shelters and many other useful products. Since Neanderthals used similar sophisticated tools in Europe, he theorized, they also had to be skilled enough to make leather products of various types.

Dr Hallett is curious to see if other archaeologists exploring human-occupied caves elsewhere in Africa will find similar evidence of ancient clothing-making practices. Now that they know such evidence exists, they’ll know what to look for and won’t dismiss findings that push the garment-making timeline even deeper into prehistoric times.

Top image: Spattered tools found on the site of the Smugglers Cave in Morocco. Source: Cell press .

By Nathan Falde

[ad_2]

Source link