[ad_1]

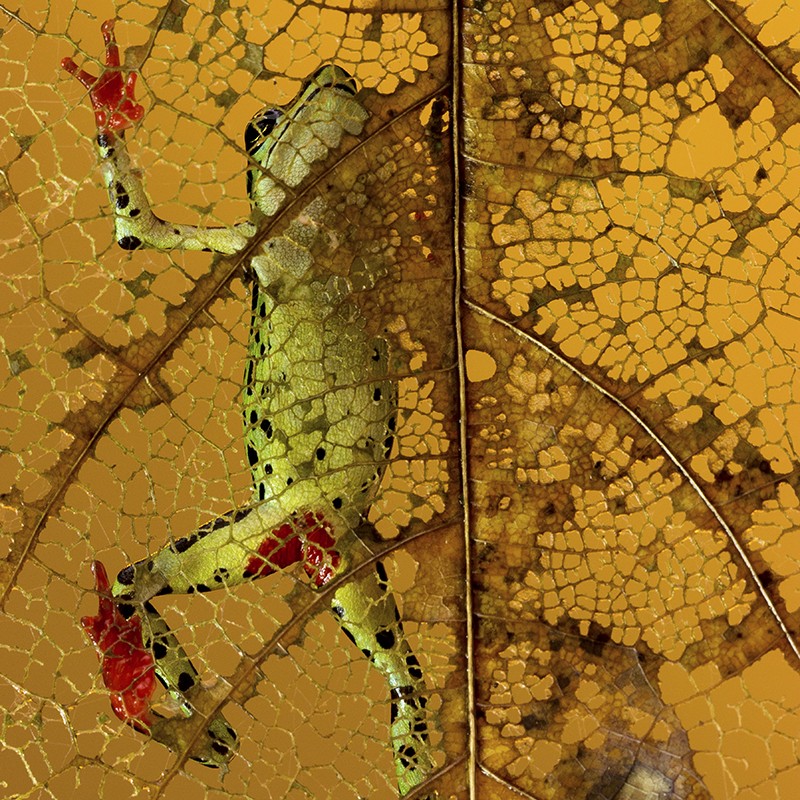

A fungus killing frogs is responsible for the decline of more species than any other registered pathogen, revealed an overall analysis.

The study, published March 28 in Science1, reveals that the chytrid fungus has caused the decline of at least 501 amphibian species worldwide from 1965 to 2015, of which 90 have disappeared.

Other well-known pathogens, such as white nose syndrome of bats disease or West Nile virus, which kills birds, have affected only a fraction of the number d & # 39; species. According to the study, the impact of this fungus on biodiversity is comparable to that of the most destructive invasive species, such as cats and rodents.

Seeing the overall effects of the mushroom summary is striking, says Stephen Price, a disease ecologist at University College London. "It's almost a bit Hollywood," he says. "We love these films about the pathogens that suddenly emerge and wipe out humanity, and we really saw something like that with regard to frogs in the real world."

Deadly mushroom

Chytrid fungi normally live in soil and water, where they decompose dead organic matter. But in 1998, scientists identified the species Batrachochytrium dendrobatidiswhich causes a fatal disease called chytridiomycosis in amphibians. The fungus attacks the skin of toads, frogs and related animals, thus preventing them from properly regulating their salt and water levels; it ends up provoking the hearts of animals.

The researchers understood that this fungus was responsible for mysterious declines in the amphibian populations of South America, Central America and Australia, where it had been introduced in the second half of Twentieth century through the trade of wildlife. But no one had added the effects of the fungus on a global scale. Benjamin Scheele, a population ecologist at the Australian National University in Canberra, has assembled a team of 41 ecologists and other experts from around the world to assess the scale of the problem.

Each researcher has collected evidence on amphibian species affected by the chytrid fungus in their area, browsing scientific literature and unpublished data, as well as interviewing other specialists.

The team found that the fungus had probably been involved in the decline of at least 501 amphibian species between 1965 and 2015. These losses ranged from relatively small losses of less than 20% to 45%. a population with complete extinctions. Atelopus, or toads, were particularly affected, with 30 species of this genus presumed extinct.

The number of species in decline peaked in the 1980s, coinciding with the spread of the fungus in Central America and Australia. A smaller peak in the 2000s seems to be related to the spread of the fungus in South America. But no species has been affected in Asia, where the fungus is native. The researchers suggest that amphibians that have evolved parallel to the fungus have developed ways to fight the infection.

The study found that only a few species from Europe and North America have experienced a decline. According to Dr. Scheele, it is possible that the chytrid fungus reached these areas earlier in the 20th century: these areas experienced a massive decline in amphibians in the 1950s and 1960s. These were attributed to the species. intensification of agriculture, but the fungus could also have been involved.

Protect frogs

Scheele says that the threat posed by pathogens to species – and the trade in wildlife that spreads them – is underestimated. "We really need to think a lot more about biosecurity," he said. And he hopes his data can help. The team found that the species that experienced the largest declines had some characteristics in common: they generally had a small distribution and lived in particularly humid regions, for example. Knowledge of these risk factors may guide attempts to protect other species.

Price sees a glimmer of hope in otherwise dark data. The researchers found that 20% of the surviving species for which data are available show small signs of recovery, suggesting that other species could also bounce back.

Sign up for the everyday Nature Briefing email

Stay informed about what matters in science and why hand-picked from Nature and other publications around the world.

S & # 39; register

[ad_2]

Source link