[ad_1]

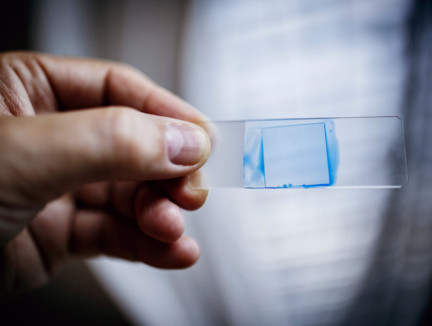

Dr. Shawn Lockhart, a fungal disease expert with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is holding a microscope slide with Candida auris inactive from an American patient.

Image credit: NYT

Last May, an elderly man was admitted to the Brooklyn Branch of Mount Sinai Hospital for abdominal surgery. A blood test revealed that he was infected with an uncovered germ, both deadly and mysterious. The doctors quickly isolated him in the intensive care unit.

The germ, a fungus called Candida auris, attacks people whose immune systems are weakened and spread unobtrusively around the world. Over the past five years, he has struck a neonatal unit in Venezuela, swept a hospital in Spain, forced a prestigious British medical center to close his intensive care unit and took root in India, Pakistan and South Africa .

Recently, C. auris went to New York, New Jersey and Illinois, where he was instructed by the Federal Center for Disease Control and Prevention to add him to a list of germs considered as "urgent threats".

Everything was positive – the walls, the bed, the doors, the curtains, the phones, the sink, the white board, the poles, the pump. The mattress, the sides of the bed, the holes in the box, the blinds, the ceiling, everything in the room was positive.

– Dr. Scott Lorin, on C. auris

The man of Mount Sinai died after 90 days of hospitalization, but not C. auris. Tests have shown that it was everywhere in his room, so overwhelming that the hospital needed special cleaning equipment and had to rip some of the ceiling and floor tile for the first time. ;eradicate.

"Everything was positive: the walls, the bed, the doors, the curtains, the telephones, the sink, the whiteboard, the poles, the pump," said Dr. Scott Lorin, president of the hospital. "The mattress, the bed rails, the box holes, the blinds, the ceiling, everything in the room was positive."

C. auris is so persistent, in part, because it is insensitive to major antifungal medications, making it another example of one of the most insurmountable health threats in the world: the resurgence of drug-resistant infections .

For decades, public health experts have warned that overconsumption of antibiotics reduced the effectiveness of drugs that prolonged life by curing bacterial infections, which were often fatal. But recently, there has also been an explosion of resistant fungi, adding a frightening new dimension to a phenomenon that undermines one of the pillars of modern medicine.

"It's a huge problem," said Matthew Fisher, professor of fungal epidemiology at Imperial College London, co-author of a recent scientific study on the rise of resistant fungi. "We depend on being able to treat these patients with antifungals."

A new breed of mushrooms

In simple terms, fungi, just like bacteria, develop defenses to survive modern drugs.

Yet even though global health leaders have called for more restraint in the prescription of antimicrobial drugs to fight bacteria and fungi – the UN General Assembly convened in 2016 to handle an emerging crisis – overuse greedy in hospitals, clinics and agriculture continued.

Resistant germs are often called "superbugs", but this is simplistic because they usually do not kill everyone. They are quite deadly for people whose immune systems are immature or compromised, including newborns and the elderly, smokers, diabetics and people with autoimmune disorders who take steroids that inhibit the defenses of the body.

Cancer versus superbug

Scientists say that unless new, more effective drugs are developed and the unnecessary use of antimicrobials is greatly reduced, the risk will spread to healthier populations. A UK government study funded projects that, in the absence of a policy to slow drug resistance, 10 million people worldwide would have died from all these infections in 2050, eclipsing the 8 million people expected from cancer that year.

In the United States, two million people become infected each year and 23,000 die, according to official CDC estimates. This number was based on 2010 figures; More recent estimates from researchers at the University of Washington's School of Medicine report 162,000 deaths. The number of deaths from resistant infections worldwide is estimated at 700,000.

Antibiotics and antifungals are essential for fighting infections in humans, but antibiotics are also widely used to prevent disease in farm animals and antifungals are also used to prevent rotting of agricultural plants. Some scientists cite evidence that the widespread use of fungicides on crops contributes to the recrudescence of drug-resistant fungi that infect humans.

However, as the problem grows, the public misunderstands it – in part because the very existence of resistant infections is often hidden in secrecy.

With bacteria and fungi, hospitals and local governments are reluctant to disclose outbreaks for fear of being considered as outbreaks of infection. Even the CDC, under its agreement with states, is not allowed to make public the location or name of hospitals involved in outbreaks. State governments have in many cases refused to publicly share information beyond simple case recognition.

During all this time, germs spread easily – carried by hands and equipment in hospitals; ferries on vegetables fertilized with meat and manure from farms; transported across borders by travelers and on exports and imports; and transferred by patients from the retirement home to the hospital.

C. auris, which infected the man of Mount Sinai, is one of dozens of dangerous bacteria and fungi that have developed resistance. Yet, like most of them, it is a threat virtually unknown to the public.

The question at hand

Of the other important strains of Candida fungus – one of the most common causes of blood infections in hospitals – have not developed significant drug resistance, but more than 90% of C. auris infections are resistant to at least one drug and 30% are resistant to two or more drugs, the CDC said.

Dr. Lynn Sosa, Connecticut's associate epidemiologist, said she now sees C. auris as the main threat among resistant infections. "It's pretty unbeatable and difficult to identify," she said.

According to the CDC, nearly half of patients who contract C. auris die within 90 days. Yet, the world experts have not specified where he came from.

"It's a black lagoon creature," said Dr. Tom Chiller, head of the mushroom branch at CDC, which spearheads a global detective effort to find treatments and stop the spread . "He's bubbling and now he's everywhere."

"No need" to tell the public

In late 2015, Dr. Johanna Rhodes, an infectious disease expert at Imperial College London, had a panicked call from the Royal Brompton Hospital, a British medical center located outside of London. C. auris had taken root there months earlier and the hospital could not clean it.

"We have no idea where it comes from. We have never heard of it. It's a real spread, it's like wildfire, "said Dr. Rhodes. She agreed to help the hospital identify the genetic profile of the fungus and clean the rooms.

Under his leadership, hospital employees used a special device to spray aerosol hydrogen peroxide around a room used for a patient with C. auris, the theory being that the Steam would foam every corner. They left the camera for a week. Then they placed a "fixation plate" in the middle of the room with a bottom gel that would serve as a breeding ground for the surviving microbes, Dr. Rhodes said.

Only one organism has rejected. C. auris.

It spread, but nothing says it. The hospital, a specialized lung and heart center that attracts wealthy patients from the Middle East and Europe, alerted the British government and informed infected patients, but made no public announcements.

"It was not necessary to issue a press release during the outbreak," said Oliver Wilkinson, spokesman for the hospital.

This muffled panic is taking place in hospitals around the world. Individual institutions and national, state and local governments have been reluctant to announce epidemics of resistant infections, saying there is no point in scaring patients – or potential patients.

Dr. Silke Schelenz, infectious disease specialist at Royal Brompton, said the lack of urgency of the government and the hospital at the very beginning of the epidemic was "very, very frustrating".

"They obviously did not want to lose their reputation," said Dr. Schelenz. "It did not have an impact on our surgical results."

At the end of June 2016, a scientific article reported "an ongoing epidemic of 50 cases of C. auris" at Royal Brompton, and the hospital has taken an extraordinary step: it closed its I.C.U. for 11 days, intensive care patients were transferred to another floor without prior notice.

A few days later, the hospital finally admitted to a newspaper that he had a problem. In the Daily Telegraph, the Daily Telegraph warned, "The intensive care unit is closed after the appearance of a new deadly Superbug bacteria in the UK."

However, the problem remained little known at the international level, while an even more serious epidemic had begun in Valencia, Spain, at the university hospital of 992 political beds. There, without the knowledge of the public and unaffected patients, 372 people were colonized – which means they had the germ on their body but were not sick – and 85 developed blood infections. An article in the journal Mycoses reported that 41% of infected patients had died within 30 days.

A statement from the hospital indicates that it is not necessarily C. auris who killed them. "It is very difficult to determine if patients are dying from the pathogen because they are patients with many underlying diseases and the general condition is very serious," the statement said.

As with Royal Brompton, the Spanish Hospital has made no public announcement. He still has not.

An author of the article Mycoses, a hospital doctor, said in an email that the hospital did not want him to talk to reporters because he "worries about the public image of the hospital".

The secret irritates the advocates of patients' rights, saying that people have the right to know if there is an outbreak in order to decide whether or not they should go to the hospital, especially if it is about a non-urgent case, such as elective surgery.

"Why the hell are we talking about an outbreak nearly a year and a half later – and we do not have it on the front page the next day?" Said Dr. Kevin Kavanagh, physician in Kentucky and chairman of the Health Watch USA board of directors. a nonprofit patient advocacy group. "You would not tolerate that in a restaurant where there was food poisoning."

Health officials say the revelation of the outbreaks scares patients of a situation they can not do anything about, especially when the risks are unclear.

"It's hard enough, with these organizations, that health care providers surround themselves," said Dr. Anna Yaffee, former CDC. epidemic investigator who has had to cope with outbreaks of resistant Kentucky infections in which hospitals have not been publicly disclosed. "It's really impossible to get a message out to the public."

Officials in London alerted the CDC of the Royal Brompton outbreak during its appearance. And the C.D.C. realized that the message had to be passed on to American hospitals. On June 24, 2016, the C.D.C. issued a national warning to hospitals and medical groups and created an email address ([email protected]) to respond to inquiries. Dr. Snigdha Vallabhaneni, a key member of the fungal team, was waiting to receive a net – "maybe a message every month".

Instead, after a few weeks, his inbox exploded.

Coming to America

In the United States, 587 cases of persons with C. auris have been reported, including 309 in New York, 104 in New Jersey and 144 in Illinois, according to C.D.C.

The symptoms – fever, body aches and fatigue – are apparently ordinary, but when a person is infected, especially someone already in poor health, such common symptoms can be fatal.

[ad_2]

Source link