[ad_1]

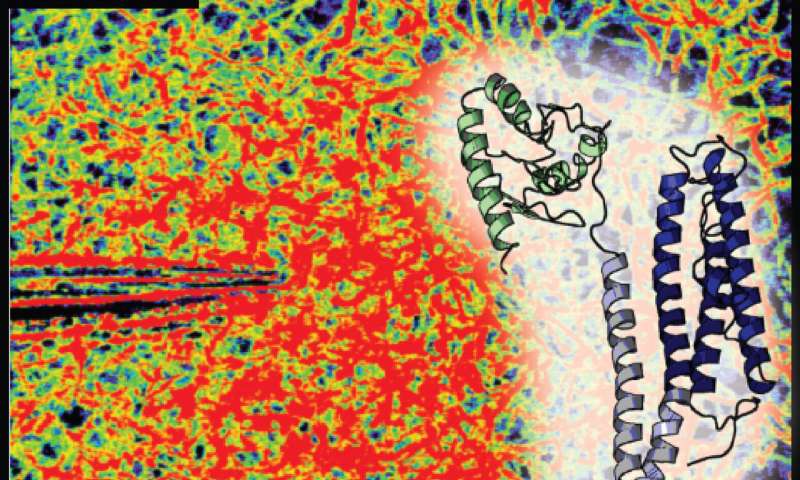

At the top, a thermal map showing H. pylori swarming towards a source of bleach. The TlpD protein that detects bleach is indicated in the box. Credit: Arden Perkins

Researchers at the University of Oregon have discovered a molecular mechanism by which the pathogen of the human stomach Helicobacter pylori is attracted to bleach, also known as hypochlorous acid or HOCI. The study revealed that H. pylori uses a protein called TlpD to detect bleach and swim towards it, and that Salmonella enterica and Escherichia coli bacteria can use TlpD type proteins to detect bleach in the environment .

The researchers propose H. pylori uses TlpD protein to detect tissue inflammation sites, which could help bacteria to colonize the stomach and possibly locate damaged tissues and nutrients. The paper, "Helicobacter pylori detects bleach (HOCI) as a chemoattractant using a cytosolic chemoreceptor ", was published August 29 in the newspaper PLOS Biology.

The health burden caused by H. pylori Researchers say it is particularly important because it infects nearly half of the world's population with nearly 100% infection in some developing regions. The bacterium resides in small pockets in the stomach, called gastric glands, believed to shelter it from the hostile gastric environment.

H. pylori causes chronic inflammation and stomach ulcers. It is a major risk factor for stomach cancer, one of the most prevalent forms of cancer in the world.

"Part of the reason for studying this particular protein is that we know the navigation system that Helicobacter pylori Arden Perkins, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oregon, said: "If we come to learn what is the function of this protein, it is possible that the bacterium is able to infect and cause disease." we may be able to disrupt its function with a new drug. "

H. pylori, like most bacteria, use special proteins to detect chemicals in their environment. The process, known as chemotaxis, allows them to regulate their flagella to swim towards or away from the compounds they encounter.

The research team is committed to determining how bacteria respond to the presence of bleach, produced by white blood cells in the body and playing a key role in how the immune system fights bacteria.

"It's important that we understand the protein mechanism of bleach detection," said Karen Guillemin, co-author of the study, a professor of biology and a member of the Institute of Biological Sciences. Molecular biology of UO. "It turns out that it's not a machine that's exclusive to Helicobacter pylori and this allows us to better understand other bacteria with similar proteins. "

Work began two and a half years ago to determine the molecular function of the TlpD protein, which researchers knew was involved in regulating the flagella of the bacterium. They knew that TlpD was a sensor molecule, but they did not know what they might feel. In order to fully understand the function of the uncharacterized protein, Perkins isolated the TlpD protein and two other proteins involved in the signaling of the molecular signal to the flagella.

"Isolating the components of the molecular signaling system allowed us to better understand what was happening," said Guillemin.

Previous research had revealed that reactive oxygen species could be the compounds detected by the TlpD protein. Perkins has therefore tested different compounds, including hydrogen peroxide, superoxide and bleach. Surprising results showed that TlpD produced an attractive signal when exposed to bleach.

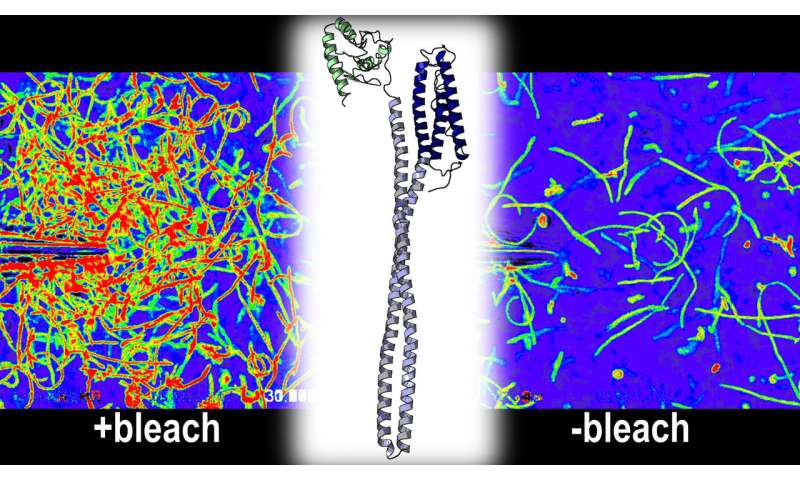

Helicobacter pylori, the pathogen of the stomach, swims to a needle filled with bleach. The bacterium uses a protein called TlpD (center) to detect bleach as an attractant. Credit: Arden Perkins

Although it seemed counterintuitive that bacteria were attracted by a harmful chemical, subsequent studies using live bacteria confirmed that bacteria are not damaged and attracted to bleach sources at concentrations produced by the human body. .

Perkins and his colleagues could not deny what they saw after repeating the experiment and controlled different explanations.

"This project started from this very rigorous molecular idea, and then we started thinking about what it meant for the behavior of the bacteria," said Guillemin. "We were able to proceed with great confidence in the fact that the phenomenon we are studying made sense at the molecular level."

Normally, the bleach produced during the inflammation is effective in killing bacteria. But H. pylori is unusual to settle in inflamed tissue for decades, apparently without being eradicated by bleach. The research team believes H. pylori may be attracted by bleach as a means of localization and persistence within the gastric glands, rich in white blood cells but serving as essential reservoirs for the bacteria.

Surprisingly, the researchers discovered that the toxic compound produced by white blood cells could be interpreted as a signal of attraction by the invading bacterium.

"We know that during its infection, the bacteria is able to live in inflamed tissues for years and years, so this result suggests that some of the way it does it is d & # 39; 39 be attracted to inflamed tissue, "said Perkins. "He has clearly developed enough protections to be able to withstand this environment, even if it contains potentially high concentrations of bleach."

The researchers found that TlpD-like proteins from Salmonella enterica and Escherichia coli are also able to detect bleach, which indicates that bleach detection can be a phenomenon up to the point of bleach. then unrecognized practiced by many types of bacteria.

The research could eventually lead to new treatments to disrupt the ability of harmful bacteria to detect their environment and could have implications for reducing antibiotic resistance.

Typical antibiotics used clinically today kill or prevent bacteria from dividing by targeting elements such as the bacterial cell wall. As a result, bacteria are under selective pressure to develop resistance to these drugs in order to survive.

In the case of Helicobacter pyloriabout 30% of infections are resistant to antibiotics. With a deeper understanding of the mechanisms at work, Guillemin said, researchers could then be able to develop more effective ways of fighting bacteria.

"It may be that bacteria are under less selective pressure to defeat a drug that simply makes them disoriented," said Guillemin. "By 2050, there will be a pandemic of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, so it's really necessary to think about new strategies."

Scientists are discovering the origin of a cellular mask that hides cancer from the stomach

Arden Perkins et al., Helicobacter pylori, detects the bleaching agent (HOCl) as a chemoattractant using a cytosolic chemoreceptor, PLOS Biology (2019). DOI: 10.1371 / journal.pbio.3000395

Quote:

New research reveals that a pathogen of the human stomach is attracted to bleach (August 29, 2019)

recovered on August 29, 2019

from https://phys.org/news/2019-08-reveals-human-stomach-pathogen.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair use for study or private research purposes, no

part may be reproduced without written permission. Content is provided for information only.

[ad_2]

Source link