[ad_1]

California scientists have discovered a local strain of coronavirus that appears to be spreading faster than any other variant roaming free in the Golden State.

Two independent research groups said they came across the new strain while looking for signs that a highly transmissible variant from the UK had established itself here. Instead, they found a new branch of the virus’s family tree – whose sudden rise and distinctive mutations made it a prime suspect in California’s vicious vacation wave.

As they looked at the genetic sequencing data in late December and early January, both teams saw evidence of the prolific spread of the new strain emerging from their spreadsheets. While focused on different parts of the state, they revealed trends that were both remarkably similar and deeply disturbing.

Researchers at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles found that while the strain was barely detectable in early October, it accounted for 24% of about 4,500 viral samples collected from across California in the last weeks of 2020.

In a separate analysis of 332 virus samples taken primarily from northern California in late November and December, 25% were of the same type.

“There was a local variant under our noses,” said Dr. Charles Chiu, a laboratory medicine specialist at UC San Francisco, who examined the samples from the northern part of the state with collaborators from the Department of. California Public Health. If they weren’t looking for the British strain and other viral variants, he said, “we could have missed this on every level.”

The new strain, which scientists have named B.1.426, carries five mutations in its genetic code. One of them, known as L452R, modifies the virus spike protein, the tool it uses to infiltrate human cells and turn them into virus-making factories.

Over several generations, even a small improvement in this ability will help a virus spread more easily in a population, causing infections, hospitalizations, and death.

Uneven surveillance efforts that use genetic sequencing to track changes in the virus had detected a single instance of B.1.426 in California in July. As far as scientists can tell, it remains low for the next three months.

Then he got busy.

The Cedars-Sinai team collected 192 viral samples from patients at the medical center between November 22 and December 28. At 11 p.m. on New Years Eve, they uploaded these samples to their genetic sequencer, which began spitting out the data on the first weekend of the New Year. The stump’s sudden prominence elicited both wonder and pain.

“We said, ‘Wow! There is something different, something we didn’t expect to find, ”said Dr. Eric Vail, a pathologist who typically sequences genes for cancer factors. “All of a sudden your brain starts doing a mile a minute.”

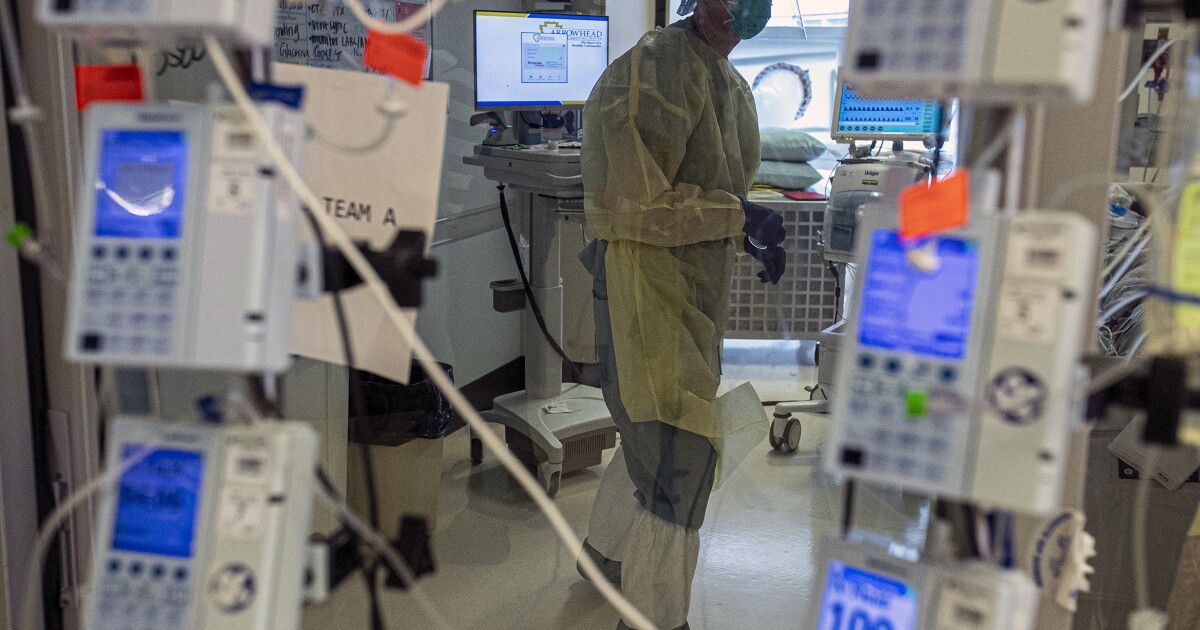

All thoughts quickly turned to the state’s calamitous COVID-19 outbreak – a rise in disease and death that has stressed hospitals to their limits, killed more than 18,000 Californians and doubled the total death toll. state in less than three months.

Had they found the culprit?

The preliminary evidence seemed overwhelming. He was certainly found at the scene of the crime. Baffled health officials working to contain the outbreak had speculated they were facing a new strain of coronavirus with improved transmission abilities.

But there were several other suspects to consider as well, including cold weather, restaurant meals, holiday gatherings and a growing disregard for public health measures.

To clarify the role of B.1.426 in the outbreak, investigators will need to determine how much devastation it is capable of producing. This investigation will focus on its transmissibility as well as its ability to bypass tools – including masks, drugs and vaccines – that can be used to bring the pandemic under control.

For now, the two groups of researchers doubt they have found a single actor. But they may have caught an accomplice.

Chiu said her skepticism stems in part from the fact that the surge in cases statewide appears to have started before the new strain experienced its strongest growth. “It may have contributed to that surge, or just accompanied the trip,” he says.

In addition, the strain’s sudden prominence among viral samples from Northern California may be due in part to its role in an unusually large outbreak at Kaiser Permanente San Jose Medical Center that has infected at least 77 staff and 15 patients. , and resulted in the death of an employee. Officials are investigating whether an infected but asymptomatic employee was able to widely spread the virus using a battery-powered ventilator that is part of an inflatable Christmas tree costume.

“It seemed to be spreading pretty quickly,” said Dr Sara Cody, health official for Santa Clara County, where the hospital is located. “We are trying to understand whether the characteristics of this epidemic are due to this variant – does this variant of the virus behave in a different way – or is it related to other factors present in the hospital?”

In southern California, where the time frames for the surge and the emergence of B.1.426 seem better aligned, researchers are more inclined to blame the virus.

“It probably helped speed up the number of cases over the holiday season,” Vail said. “But human behavior is the predominant factor in the spread of a virus, and the fact that it happened when the weather turned colder and in the middle of the holidays when people are gathering is no accident.”

Scientists in Chiu’s lab have already started cultivating armies of the new strain, derived from four recently infected patients. Creating large batches under controlled conditions is a first step in testing whether any of its mutations improve its ability to attach, invade, and hijack human cells.

These early efforts have raised concerns.

“It grows quite vigorously,” Chiu said.

Adding to his concern, the findings of other researchers at Howard University who designed and tested a version of the coronavirus with the L452R mutation, which rose to prominence in a strain that surfaced in Denmark in March. The Howard team found that the mutation helped the virus attach more firmly to human cells, potentially improving its transmission.

In Chiu’s lab, as well as at Cedars-Sinai, scientists will test the new strain for signs that the B.1.426 mutations improved its performance.

Other experiments will explore whether the antibodies generated by the immune system of people infected or vaccinated against the coronavirus will recognize this new strain.

Overwhelming evidence has already emerged. State health officials reported this week that a patient from Monterey County who tested positive for infection in April and recovered has now been infected with B.1.426.

This suggests that the new strain may be able to hide its presence of antibodies created after exposure to other versions of the virus – a phenomenon known as ‘immune leakage’. If so, it could affect the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines and antibody-based treatments.

“The bottom line is that this is a variation that is becoming more and more prevalent and we need to look into it and understand more,” said Cody.

[ad_2]

Source link