[ad_1]

Of all the human species that have ever existed, Homo sapiens (modern man) is the only survivor. But that doesn’t make us as special as we thought. A genetic study conducted by researchers at the University of California at Santa Cruz (UC Santa Cruz) found that modern humans have only a small fraction of totally unique human DNA. The vast majority of our collective genetic makeup is something that we shared with other species of ancient men, especially our long extinct “cousins” Neanderthals and Denisovans.

So how much human DNA is ours exclusively and has never been carried by another human species? Only seven percent, the researchers responsible for this research explain in their Scientists progress review of the journal.

“That’s a pretty low percentage,” Nathan Schaefer, computer biologist and co-sponsor of the UC Santa Cruz study, told The Associated Press. “This kind of discovery is the reason why scientists are turning away from thinking that we humans are so different from Neanderthals.”

That seven percent is something we share with all modern humans who have lived and died for the past 200,000 years, the approximate time that has passed since the first evolution of Homo sapiens. Of these seven percent, the majority is present in some people but not in others. Only 1.5% of their DNA is both unique to us and shared by everyone who currently lives on the planet.

Modern humans are not a singular or special creation of evolution. They are mostly a mixture of genetic material from other ancient species, all of which developed long before the appearance of Homo sapiens.

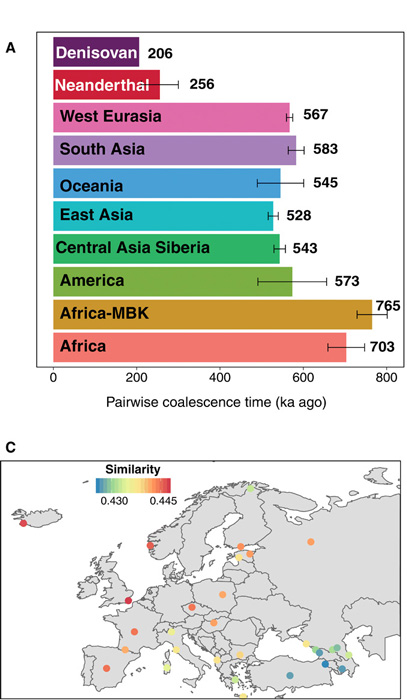

Fig. 2 of the Science Advances study: Performance of SARGE on SGDP and archaic hominin dataset: (A) Pairwise coalescence time for randomly sampled sets of up to 10 pairs of genome haplotypes per phase per population in ka (thousands of years ago). The values are calibrated using a human-chimpanzee divergence time 13 million years ago (13 Ma). (B) Unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean trees calculated using the nucleotide diversity of the SNP data (top and left) versus the similarity matrix of shared recombination events deduced by SARGE ( Speedy Ancestral Recombination Graph Estimator). ( Scientists progress )

Tracking of shared genetic inheritance in human DNA

To complete this study, the UC Santa Cruz team of researchers examined genetic data collected from the fossilized remains of Neanderthals and Denisovans who lived between 40,000 and 50,000 years ago. They compared this ancient DNA to genetic material extracted from 279 people living today, looking for overlaps and differences.

Since ancient genomes taken from human fossils are not always complete, this is a difficult comparison to make. But the researchers developed a method that allowed them to fill in the blanks when information was missing in ancient genomes. As a result, they were able to identify all of the genetic material shared between modern humans and Neanderthals or Denisovans, who made up 93% of the total found in the Homo sapiens genome.

It’s important to point out that Neanderthals and Denisovans are not the direct ancestors of Homo sapiens (we did not evolve from them, in other words). Instead, they share common ancestors with us, which is why they are often referred to as our cousins. The 93 percent of our DNA that we share with Neanderthals and Denisovans was inherited from these ancestors, who lived on earth millions of years ago.

It shows just how close the genetic relationship between these three species was and explains how humans were able to interbreed with each other despite their differences.

Crossbreeds are known to have taken place, as a small part of the human genetic code contains DNA inherited from Neanderthals and Denisovans (crosses with Neanderthals were much more common). Modern humans began to migrate out of Africa and spread across the planet in significant numbers between 100,000 and 70,000 years ago. They would have lived side by side with the other two species for about 50,000 years after that, until the Denisovans and Neanderthals became extinct (the exact dates on which this happened are disputed).

It is possible to see the decision of Neanderthals and Denisovan to crossbreed with modern humans as a kind of survival strategy. In doing so, they ensured that their species would never go extinct. They still exist today, like traces of DNA that still shape our development.

So what is it that makes humans unique? The answer is neural development and brain function. The brain of this modern woman is “wired” differently from the brains of our prehistoric ancestors. ( reason / Adobe Stock)

Human uniqueness? Neural development and brain function!

Some of the most revealing information obtained in this new study emerged from an analysis of 1.5% of modern human DNA that is shared by everyone. Further study of this genetic material could help scientists understand what separates Homo sapiens from other human species, as it never existed in these other species but is universal in us.

“We can say that these regions of the genome are highly enriched in genes related to neural development and brain function,” explained UC Santa Cruz computational biologist Richard Green, co-author of the Scientists progress to study.

The main objective of this study was to find out what genetic factors make modern humans unique. Homo sapiens is the only hominin (the biological group made up of modern humans, extinct humans, and all of our immediate ancestors) that survived into the modern era, meaning it likely possessed qualities that were lacking. to others.

It is presumed that the advantage had something to do with cognitive abilities. This would appear to make the discovery of unique genes in humans that affect mental development and brain function highly significant.

Of course, it’s possible that Homo sapiens survived by luck rather than skill. As populations of the three species increased, Homo sapiens may have been living in the right places at the right times, enjoying a more favorable climate and better access to food and water when resources were available. have started to become scarce.

Most likely, luck and evolutionary benefits both played a role in deciding the end result.

Top image: Neanderthal skull (left) compared to a modern human skull (right). A recent study found that only 7% of human DNA is unique. The remaining 93% of human DNA is shared with our old “cousins” the Neanderthals and Denisovans. Source: procy_ab / Adobe Stock

By Nathan Falde

[ad_2]

Source link