[ad_1]

The oceans of the world are preparing to spray all that 1980s hair spray all over our faces. Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), the aerosolized chemicals that tore a hole in the Earth’s protective ozone layer in the years after their mass production, are expected to make a comeback at the end of the 21st century, in an accelerated process by climate change, say the researchers.

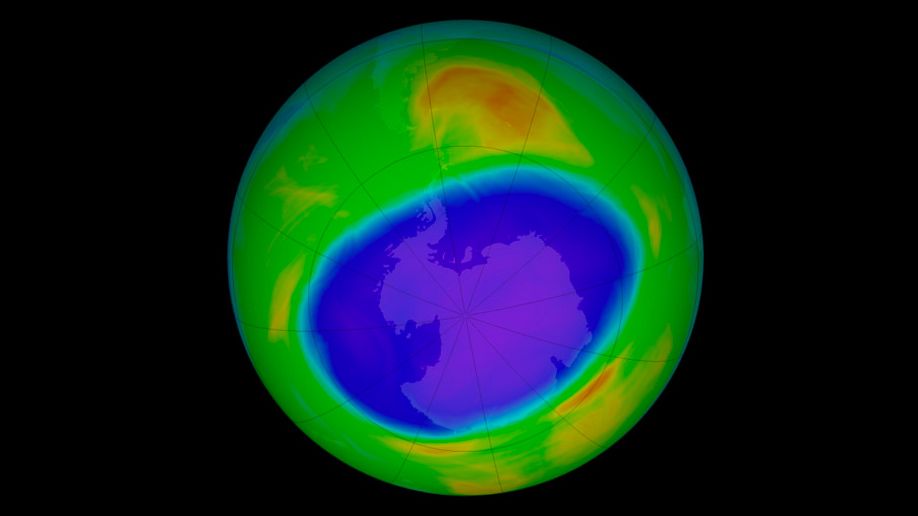

The Montreal Protocol banned the use of CFCs worldwide in 1987, after researchers discovered that CFCs had damaged the ozone layer that protects life on Earth from harmful ultraviolet rays. And the Montreal Protocol mostly worked – levels of CFCs in the atmosphere have dropped sharply over the past few decades, and the ozone layer has started to repair itself. Live Science reported. But all those CFCs already released into the atmosphere had to go somewhere. And for many of these molecules, it was somewhere in the oceans of the world.

Now, a new study projects that when CFC levels in the atmosphere drop and the oceans warmer, some of these latent ozone gobblers will end up in the air – almost as if a country decides to start emitting them again. .

This is because the ocean and the atmosphere tend to stay in balance. When the atmosphere contains a lot of water soluble molecules, such as a CFC, the oceans absorb some of them. And when the oceans contain a lot of this same molecule, but the atmosphere does not, they tend to release it into the air. As the world has stopped producing CFCs, atmospheric levels of CFCs have dropped and the oceans are absorbing less and less air. Eventually, the balance will shift and the oceans will become net emitters of CFCs. Climate change is warming the oceans, reducing the amount of CFCs a gallon of ocean water can hold, speeding up the process. This new study shows when all of these factors are expected to come together and transform the oceans of CFC sponges into CFC emitters.

“By the time you get to the first half of the 22nd century, you will have enough flow coming out of the ocean to make it look like someone is cheating on the Montreal Protocol, but instead it could just be what’s coming. out of the ocean, ”study co-author and MIT environmental scientist Susan Solomon said in a press release.

Related: 10 climate myths shattered

CFCs are synthetic compounds made up of carbon atoms bonded with chlorine and fluorine atoms. Because they are inert, non-flammable, and non-toxic, CFCs were used in refrigerants, spray cans, and other household and industrial goods in the second half of the 20th century, such as Previously reported Live Science. When introduced, CFCs appeared to be a safe alternative to toxic ammonia and flammable butane. But researchers have found that CFCs tend to break down after they are released into the atmosphere, emitting chlorine that reacts with ozone molecules – each made up of three oxygen atoms – causing the degradation of ozone.

The slow repair of the ozone layer is one of the greatest global environmental success stories of all time, environmentalists often say. But researchers in the new study showed that such great success led to a drop in atmospheric CFCs that could soon prompt the oceans to release the CFCs they have absorbed.

When the atmosphere fills with a water soluble chemical, like CFCs or even carbon dioxide, to levels much higher than those found in the ocean, the seas tend to absorb this chemical. until the marine and atmospheric concentrations reach equilibrium. (The details of this balance vary from compound to compound.)

The authors of the new article focused on CFC-11, one of the many types of CFCs covered by the Montreal Protocol. The authors estimated that about 5-10% of all CFC-11 ever manufactured and released ends up in the oceans. And because atmospheric levels of CFC-11 have remained so much higher than oceanic levels of CFC-11 so far, despite reductions due to the Montreal Protocol, most of what has been absorbed has remained unchanged.

But using careful models of ocean behavior and CFC production (actual and expected) between 1930 and 2300, researchers have shown that by 2075, atmospheric levels of CFC-11 will drop so much that the oceans will release more than they can. ‘they don’t absorb it. . And by 2145, the oceans will be releasing so much CFC-11 that – if monitors didn’t know better – it could appear that someone was in violation of the Montreal Protocol.

Climate change will accelerate this process. Assuming an average global warming of 9 degrees Fahrenheit (5 degrees Celsius) by 2100, the study authors wrote, the oceans could go from absorption to emission of CFC-11 a decade earlier than planned. (Five degrees of warming would be higher than targets set in international planning like the Paris Agreement, but more is less in line with the trajectory the planet seems to be heading towards.)

“In general, a colder ocean will absorb more CFCs,” said Peidong Wang, senior author and researcher at MIT. “When climate change warms the ocean, it becomes a weaker reservoir and will also degas a little faster.”

There is room for improvement on this model, the researchers wrote. More powerful and higher-resolution models should provide a more accurate picture of exactly how much oceanic CFC emissions can be expected and when to expect them. CFC-11 hidden in the ocean alone is not enough to destroy the ozone layer, but it could prolong its repair.

The study was published on March 15 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Originally posted on Live Science.

[ad_2]

Source link