[ad_1]

Imagine the United States struggling to deal with a deadly pandemic.

National and local authorities are adopting a series of social distancing measures, collecting bans, closure orders and masked warrants in an attempt to stem the tide of cases and deaths.

The audience responds with widespread conformity mixed with more than a hint of growls, repulses, and even outright defiance. As days turn into weeks turn into months, the restrictions become more difficult to tolerate.

The owners of theaters and dance halls complain about their financial losses.

The clergy deplore the closings of churches while offices, factories and in some cases even saloons are allowed to remain open.

Officials wonder if children are safer in classrooms or at home.

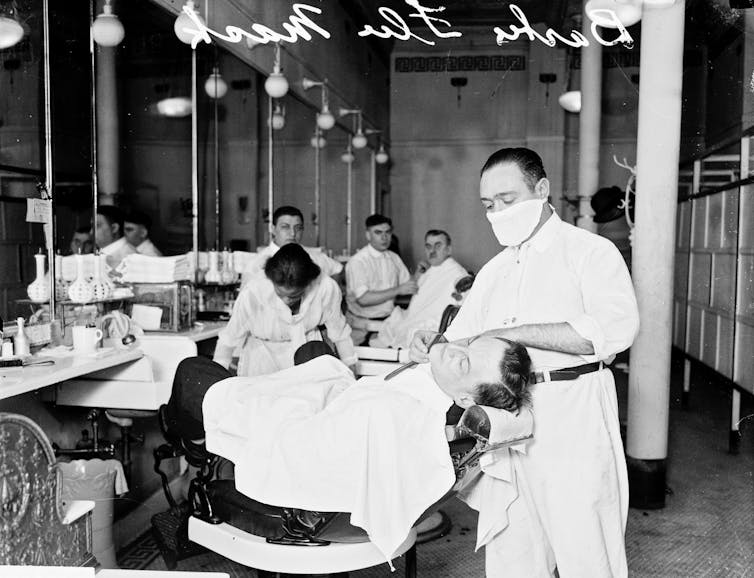

Universal History Archive / Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Many citizens refuse to wear a face mask when in public, with some complaining of being uncomfortable and others arguing that the government has no right to infringe on their civil liberties.

As familiar as it sounds in 2021, these are true descriptions of America during the deadly influenza pandemic of 1918. In my research as a medical historian, I have seen time and time again the many ways in which our current pandemic mirrored that experienced by our ancestors a century ago.

As the COVID-19 pandemic enters its second year, many people want to know when life will return to what it was before the coronavirus. History, of course, is not an exact model of what the future holds. But the way Americans came out of the previous pandemic might suggest what post-pandemic life will be like this time around.

Sick and tired, ready for the end of the pandemic

Like COVID-19, the 1918 influenza pandemic struck hard and quickly, going from a handful of cases reported in a few cities to a nationwide epidemic within weeks. Many communities have issued multiple rounds of shutdown orders – matching the ebb and flow of their epidemics – in an attempt to bring the disease under control.

These social distancing orders have helped reduce cases and deaths. Just like today, however, they have often proven difficult to maintain. In late fall, just weeks after the social distancing orders went into effect, the pandemic appeared to be coming to an end as the number of new infections declined.

PhotoQuest / Archive photos via Getty Images

People demanded to get back to their normal lives. The companies pressured officials to be allowed to reopen. Believing that the pandemic was over, state and local authorities began to reverse public health decrees. The nation has focused its efforts on the devastation caused by the flu.

For friends, families and colleagues of the hundreds of thousands of Americans who have died, post-pandemic life was filled with sadness and grief. Many of those who were still recovering from their episodes of illness needed support and care during their recovery.

In an era when there was no federal or state safety net, charities mobilized to provide resources to families who had lost their breadwinner or to welcome the countless children orphaned by disease.

For the vast majority of Americans, however, life after the pandemic seemed like a headlong rush to normalcy. Hungry for weeks on end of their nights on the town, sporting events, church services, classroom interactions and family reunions, many were eager to return to their old lives.

Drawing inspiration from authorities who had – somewhat prematurely – declared the end of the pandemic, Americans have rushed in mass to return to their pre-pandemic routines. They gathered in cinemas and dance halls, crowded into shops and stores, and gathered with friends and family.

Officials had warned the country that the cases and deaths would likely continue for months. However, the burden of public health is no longer on politics but rather on individual responsibility.

Predictably, the pandemic continued, extending into a deadly third wave that lasted until the spring of 1919, with a fourth wave striking in the winter of 1920. Some officials blamed the resurgence on Careless Americans. Others downplayed new cases or turned to more common public health issues, including other illnesses, restaurant inspections and sanitary facilities.

Despite the persistence of the pandemic, the flu quickly became old news. Once characteristic of the front pages, the report quickly reduced to sporadic small clippings buried in the backs of newspapers across the country. The nation continued, hardened by the toll of the pandemic and the deaths to come. People were largely reluctant to revert to socially and economically disruptive public health measures.

Chicago History Museum / Archive photos via Getty Images

It’s hard to stay in there

Our predecessors could be forgiven for not staying the course longer. First, the nation was eager to celebrate the recent end of World War I, an event that was perhaps more important in the lives of Americans than even the pandemic.

Second, death from disease was a much more important part of life in the early 20th century, and plagues such as diphtheria, measles, tuberculosis, typhoid, whooping cough, scarlet fever, and pneumonia each regularly killed people. tens of thousands of Americans every year. Moreover, neither the cause nor the epidemiology of the flu was well understood and many experts were still not convinced that social distancing measures had a measurable impact.

Finally, there were no effective influenza vaccines to save the world from the ravages of disease. In fact, the influenza virus would not be discovered for 15 years, and a safe and effective vaccine was not available to the general population until 1945. Given the limited information and tools available to them, Americans may have endured public health. restrictions as long as they reasonably could.

A century later, and a year after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s understandable that people are now too anxious to return to their old lives. The end of this pandemic will inevitably come, as it is with all the previous ones that humanity has known.

If we have anything to learn from the history of the 1918 influenza pandemic, as well as our experience to date with COVID-19, it is that an early return to pre-pandemic life is more likely to be. cases and deaths.

And Americans today have significant advantages over those of a century ago. We have a much better understanding of virology and epidemiology. We know that social distancing and masking helps save lives. More importantly, we have several safe and effective vaccines being rolled out, with the pace of vaccinations being increasingly weekly.

Sticking to or mitigating all of these coronavirus-fighting factors could mean the difference between another outbreak of the disease and an earlier end to the pandemic. COVID-19 is much more transmissible than the flu, and several disturbing variants of SARS-CoV-2 are already spreading around the world. The third fatal wave of influenza in 1919 shows what can happen when people let go of their guard prematurely.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

[ad_2]

Source link