[ad_1]

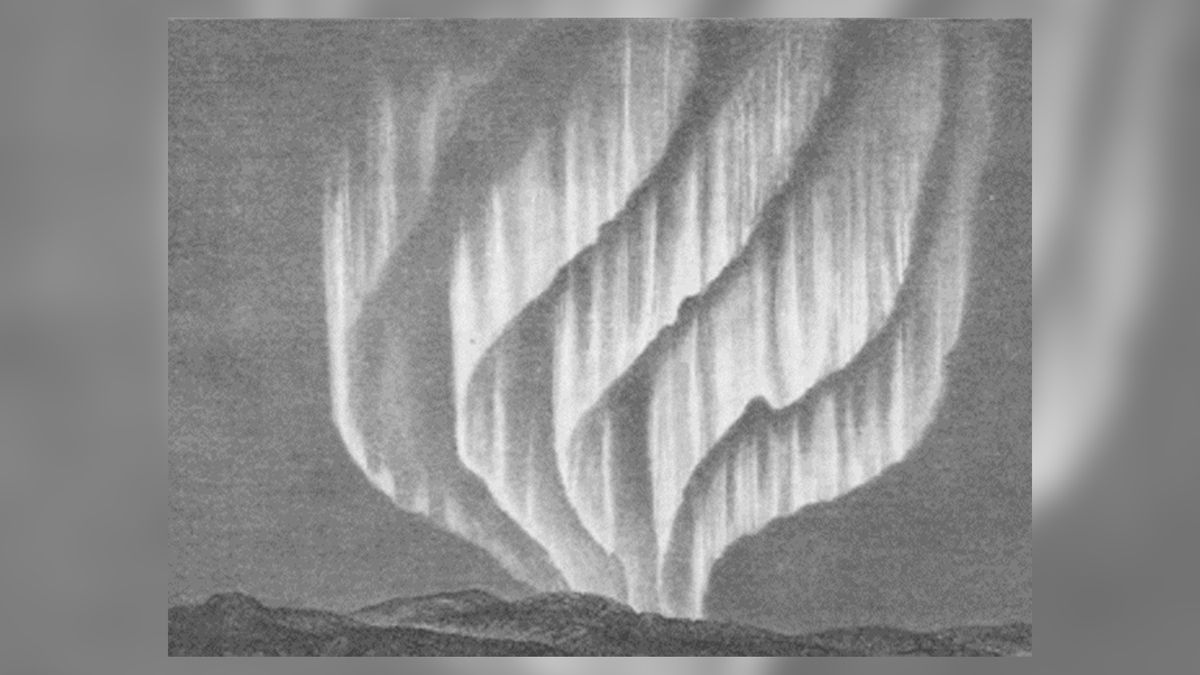

It is a question that has bewildered observers for centuries: Do the fantastic green and crimson lights of the Northern Lights produce a noticeable sound?

Summoned by the interaction of solar particles with gas molecules in Earth’s atmosphere, aurora usually occurs near the earth’s poles, where the magnetic field is strongest. Reports of aurora making noise, however, are rare – and have historically been dismissed by scientists.

But one Finnish study in 2016, claimed to have finally confirmed that the Northern Lights really do produce sound audible to the human ear. A recording carried out by one of the researchers involved in the study even claimed to have captured the sound emitted by the captivating lights 70 meters above ground level.

Related: Photos: Recording mysterious sounds of the Northern Lights

Still, the mechanism behind the sound remains somewhat mysterious, as are the conditions that must be met in order for the sound to be heard. My recent research examines historical reports of his auroral to understand methods of investigating this elusive phenomenon and the process of establishing whether the reported sounds were objective, illusory, or imaginary.

Historical claims

Auroral noise was the subject of particularly heated debate during the first decades of the 20th century, when accounts from settlements across northern latitudes reported that sound sometimes accompanied the fascinating light shows in their skies.

Witnesses reported an almost imperceptible crackling, hissing or silent hissing noise during particularly violent northern lights exposures. In the early 1930s, for example, personal testimonials started pouring in The Shetland News, the weekly from the subarctic Shetland Islands, comparing the sound of the Northern Lights to “rustling silk” or “two planks meeting on flat paths”.

These accounts have been corroborated by similar accounts from northern Canada and Norway. Yet the scientific community was far from convinced, especially since very few Western explorers have claimed to have heard the elusive noises themselves.

The credibility of auroral noise reports from this era was intimately tied to the elevation measurements of the Northern Lights. It was believed that only screens that descended low in Earth’s atmosphere would be able to transmit sound that could be heard by the human ear.

The problem here was that the results recorded during the Second International Polar Year 1932-1933 The aurora discovered most often took place 100 km above the Earth, and very rarely below 80 km. This suggested that it would be impossible for the discernible sound of the lights to be transmitted to the surface of the Earth.

Hearing illusions?

In view of these findings, prominent physicists and meteorologists remained skeptical, dismissing accounts of very low aurora and aurora sounds as folk stories or auditory illusions.

Sir Oliver Lodge, the British physicist involved in the development of radio technology, pointed out that auroral sound could be a psychological phenomenon due to the vividness of aurora appearance – just like meteors sometimes conjure up a whistling sound in the brain. Likewise, meteorologist George Clark Simpson argued that the appearance of low aurora was likely a optical illusion caused by interference from low clouds.

Nevertheless, the main auroral scientist of the 20th century, Carl Størmer, published accounts written by two of his assistants who claimed to have heard the dawn, adding some legitimacy to the large volume of personal reports.

Størmer’s assistant, Hans Jelstrup, said he heard a “very curious, distinctly wavy faint hiss, which seemed to follow exactly the vibrations of the aurora”, while Mr. Tjönn felt a sound like “from burning grass or spray “. As compelling as these last two accounts may be, they still haven’t come up with a mechanism by which auroral sound could work.

Sound and light

The answer to this lingering mystery which subsequently garnered the most support was first suggested in 1923 by Clarence Vocals, a well-known Canadian astronomer. He argued that the movement of the Northern Lights alters the Earth’s magnetic field, inducing changes in the electrification of the atmosphere, even at a significant distance.

This electrification produces a crackling sound much closer to the Earth’s surface when it encounters objects on the ground, much like the sound of static electricity. This could take place on the observer’s clothing or glasses, or possibly in surrounding objects, such as trees or the cladding of buildings.

Chant’s theory correlates well with many accounts of her auroral, and is also supported by occasional reports of the smell of ozone – which is said to have metallic smell similar to an electric spark – during the Northern Lights.

Yet Chant’s article went largely unnoticed in the 1920s, only being recognized in the 1970s when two auroral physicists revisited historical evidence. Chant’s theory is widely accepted by scientists today, although there is still debate as to how exactly the mechanism of sound production works.

What is clear is that the aurora, on rare occasions, makes sounds audible to the human ear. The eerie reports of crackling, hissing, and buzzing accompanying the lights describe an objective audible experience – not something illusory or imaginary.

Sound sampling

If you want to hear the Northern Lights on your own, you may have to spend a considerable amount of time in the polar regions, since the sound phenomenon only occurs in 5% of violent auroral manifestations. It is also heard most often on top of mountains, surrounded by only a few buildings – so it’s not a particularly accessible experience.

In recent years, the sound of the aurora has nevertheless been explored for its aesthetic value, inspiring musical compositions and laying the foundations for new ways of interacting with its electromagnetic signals.

Latvian composer riks Ešenvalds used newspaper excerpts from American explorer Charles Hall and Norwegian statesman Fridjtof Nansen, both of whom claimed to have heard the Northern Lights, in his music. Its composition, Northern Lights, interweaves these reports with the only known Latvian folk song recounting the auroral sound phenomenon, sung by a tenor solo.

Or you can also listen to the Northern Lights radio signals at home. In 2020, a BBC 3 radio program remapped very low frequency radio recordings of aurora on the audible spectrum. While not the same as perceiving the audible noises produced by the Northern Lights in person on top of a snow-capped mountain, these radio frequencies give an awe-inspiring impression of the transient, fleeting and dynamic nature of the Aurora.

This article is republished from The conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read it original article.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]

[ad_2]

Source link