[ad_1]

Tongue-like chemosensory "taste" type cells have been discovered and develop in the lungs of convalescent mice after severe influenza infection.

The discovery of these cells – also known as clumped cells – that develop in lung tissue after an infection helps us not only understand the purpose of these curious little tasters, but also explain why a single dose of flu can affect our health for life.

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania in the United States were curious about how the lungs can repair themselves as a result of an injury caused by an illness. The way in which the structure of the tissue itself seems to change after infection is particularly interesting.

Most of us heal from a bad case of flu if we have the time, to regain a level of health comparable to the one we had before staying bedridden for a few weeks.

Few unlucky will be literally changed for life, their lungs being permanently marked by a change in tissue structure that we still have trouble understanding. The consequences are a litany of physiological and psychological complications for many years.

Several years ago, researchers found that the change in the composition of lung tissue was accompanied by an inflammation that refused to disappear even after the disappearance of all other signs of infection.

In a follow-up study, the team aimed to discover the cause of this mysterious swelling.

By infecting mice with H1N1 virus and analyzing samples of their lung tissue in the following weeks, the team discovered that the chemical signals they produced were not the usual Type 1 strain associated with invasive viruses. .

Instead, they indicated a type 2 reaction – the immune response that usually helps to combat the types of threats that do not tend to sneak into cells, such as allergens and parasites.

"These distinctive signs of a type 2 immune response after a flu were unexpected and remained largely unnoticed until recently," says biologist Andrew Vaughan.

All the signs indicated the presence of a strange cell with an undisciplined cut.

The cells of the bunch are present throughout our digestive system, nested in the epithelial lining with their mop of microvilli projecting into the cavernous intestine.

Observed for the first time more than half a century ago, they have long confused scientists with their omnipresent presence and mysterious role.

On the one hand, these pear-shaped epithelial cells are very similar to the cells present in the taste buds, with receptors that respond to the presence of the types of chemical compounds that we associate with bitter and sweet flavors.

But they were quickly found not only in the intestine, but in a wide range of liners, from the inner walls of the trachea to those of the urethra.

A logical hypothesis would be that their tasting talent is used in various places, but until recently, their job description was not very clear.

Indices indicated an immune response. A separate study recently published by a team from the College of Life Sciences in China has also provided a better understanding of the protective mechanisms of bunch cells against nematode parasite infestations. Trichinella spiralis.

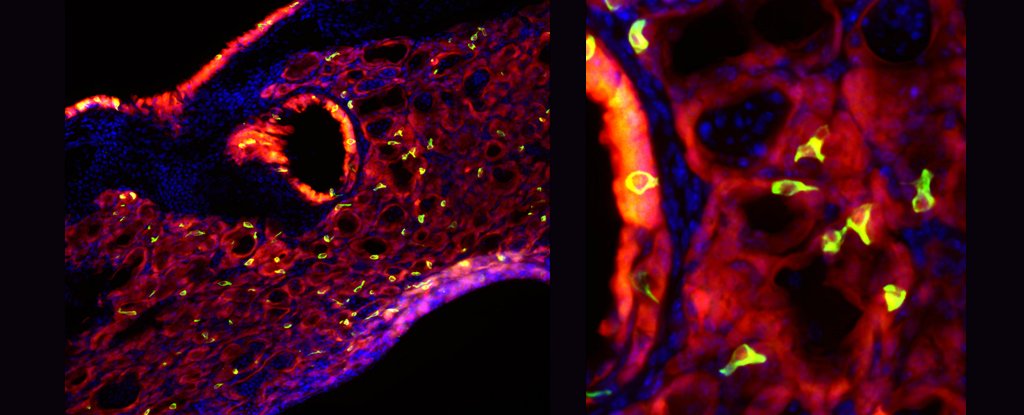

Noticing a red flag type 2, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania searched for these suspicious tuft cells in the air sacs of the alveoli inside the mouse lungs. And they were not disappointed.

"It was really very strange to see, because those cells are not in the lung initially," Vaughan says.

"The closest of them are normally in the trachea.What we did was to show from where they come from and how that same type of rare cell that gives you all that unsuitable lung remodeling after the flu is also the source of these ectopic tufted cells. "

To see if these taste cells reacted chemically, the team tried to activate them with a dose of bitter compounds. Not only did the cells react by dilating, but they also triggered an acute episode of inflammation.

None of this happened in the lungs of mice that had not contracted the flu.

The next steps will be to determine exactly the impact of their presence on the lung's healing capacity after infection and to look for the same spontaneous appearance of clump cells in human lung tissue.

The fact that clump cells have also been observed in the lungs of asthmatics and that nasal polyps can also fill gaps in type 2 immune responses and indicate how an infection can lead to a lifelong disorder.

Much remains to be discovered about these mediators of taste and immunity. But given what has been found so far, they could be the key to preventing, even treating, various health problems in the future.

This research was published in the American Journal of Physiology – Cellular and molecular physiology of the lungs.

Source link