[ad_1]

Metals and insulators are the yin and yang of physics, with their respective material properties strictly dictated by the mobility of their electrons – metals must conduct electrons freely, while insulators hold them in place.

So when physicists at Princeton University in the United States found a quantum quirk of metals bouncing inside an insulating compound, they were lost for an explanation.

We’ll have to wait for more studies to find out exactly what’s going on. But an enticing possibility is that an unprecedented particle is at work, a particle that represents neutral ground in the behavior of electrons. They call it a “neutral fermion”.

“It was a total surprise,” says physicist Sanfeng Wu of Princeton University in the United States.

“We asked ourselves, ‘What is going on here? We do not yet fully understand it. “

The phenomenon at the center of the discovery is quantum oscillation. As the term suggests, it involves the back and forth of free-moving particles under certain experimental conditions.

To be a bit more technical, oscillations occur when a material is cooled to levels where quantum behaviors more easily dominate and a magnetic field is applied and varied.

Rising and falling the magnetic field causes unattached charged particles, such as electrons, to slide between bands of energy called Landau levels.

It is a technique commonly used to study the atomic landscape occupied by electrons through a material, especially in those with metallic properties.

It is believed that isolators are a whole different pot of fish. With their electrons following strict stay-at-home orders, quantum oscillations are not a thing. At least they shouldn’t be.

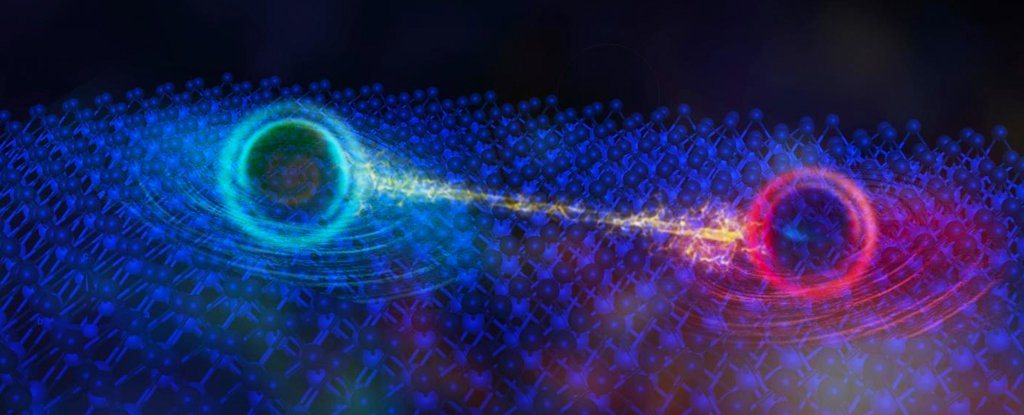

The team looked at tungsten ditelluride, a strange semi-metal that takes on the properties of an insulator when bathed in a magnetic field – and was surprised to see quantum oscillations occur.

Despite the shock, they have some thoughts on what could happen. While a fluid charge would make this insulator a conductor (which is a paradox), having a “ flow ” of neutral particles would suit the bill of the insulator and the quantum oscillator, this which makes more sense.

“Our experimental results are in conflict with all existing theories based on charged fermions, but could be explained in the presence of neutrally charged fermions,” adds his colleague Pengjie Wang.

The only problem is that truly neutral fermions should not exist, according to the Standard Model of particle physics.

Fermions are particles which are much like the “Lego blocks” of matter, while the other type of fundamental particles are bosons – charge-bearing particles.

A truly neutral particle is also its own antiparticle – and this is something we’ve seen in bosons, but never in fermions.

So finding a truly neutral fermion would likely rewrite our understanding of physics, but that’s not what researchers think is going on here – rather they think what they’ve detected is more of a neutral quasi-particle, which is a quantum type of hybrid particle. .

To understand what a quasi-particle is, imagine particle physics as a study of music.

Fundamental particles like quarks and electrons are individual instruments. They form the basis of a variety of larger particles, from three-part rock bands like protons to symphonies like whole atoms.

Bands that play in sync on opposing stages can even be seen as a one-time event – a quasi-item that for all purposes plays as one.

Quantum strangeness can coat the properties of electrons in such a way as to make fractions of their charge through spaces. In other words, some electron quasiparticles will carry bits of the electron, like its spin, but not its charge, thus creating a neutral version of itself.

The exact flavor of the quasi-particle operating here (if any) remains to be determined, but the researchers describe it as completely new territory not only in experimentation, but in theory.

“If our interpretations are correct, we are witnessing a fundamentally new form of quantum matter,” Wu says.

“We now imagine a whole new quantum world hidden in isolators. It is possible that we have simply failed to identify them in recent decades.

Neutral fermions have a potential role in improving the stability of quantum devices, so finding proof of this here would be more than an academic curiosity, with promising practical applications.

It’s still early. But so many scientific discoveries have emerged from these timeless words: “What’s going on here?

This research was published in Nature.

[ad_2]

Source link