[ad_1]

Bone plates called osteoderms (orange in color) cover the skull of an adult Komodo dragon. Credit: University of Texas at Austin.

Just under their scales, Komodo dragons wear armor made of tiny bones. These bones cover the dragons from head to toe, creating a "coat of mail" that protects giant predators. However, armor raises a question: what does the world's largest lizard – the dominant predator in its natural habitat – need protection?

After scanning Komodo dragon specimens with powerful X-rays, researchers at the University of Texas at Austin think they have an answer: Other Komodo dragons.

Jessica Maisano, a scientist at the UT Jackson School of Geosciences, led the research, published on September 10, 2019, in the journal The anatomical file. His co-authors are Christopher Bell, professor at the Jackson School; Travis Laduc, Assistant Professor at the College of Natural Sciences of UT; and Diane Barber, curator of cold-blooded animals at Fort Worth Zoo.

Scientists have come to their conclusion using Computerized Tomography (CT) technology to examine inward and digitally reconstruct the skeletons of two dead dragon specimens – an adult and a baby. The adult was well equipped with armor, but she was completely absent in the baby. This is a finding that suggests that bone plates do not appear before adulthood. And the only thing that adult dragons need to be protected is the other dragons.

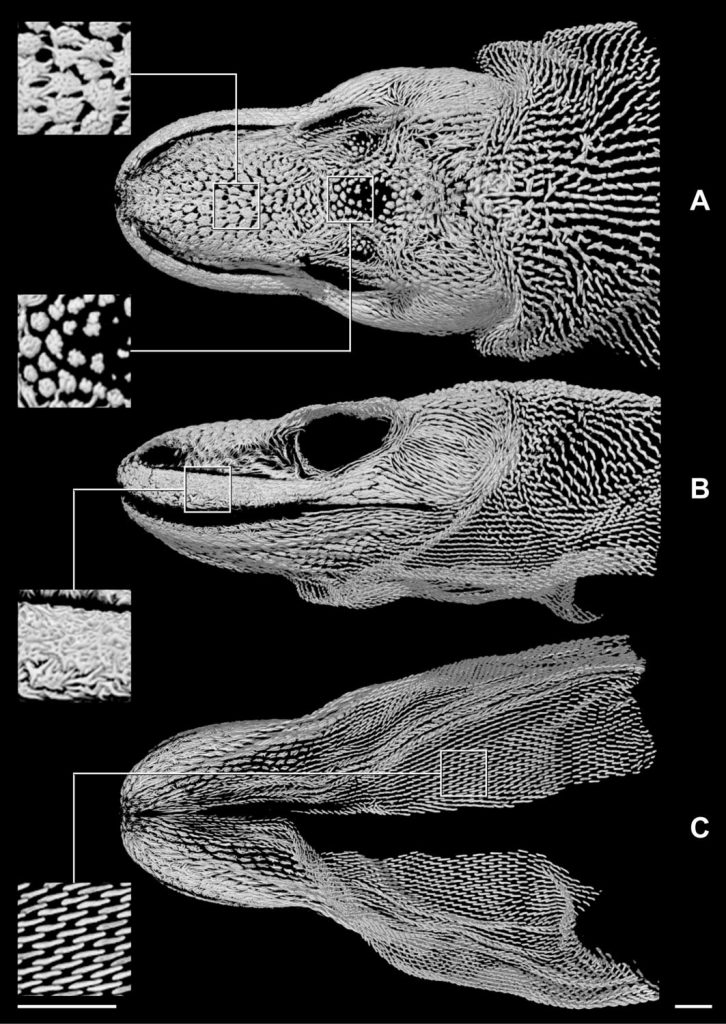

Osteoderms of the Komodo dragon. The inserts show the four basic osteodermal forms found on the adult specimen. From top to bottom: rosette; platy; dendritic; and vermiform. Credit: University of Texas at Austin.

"The young komodo dragons spend a lot of time in the trees, and when they're old enough to get out of the tree, that's when they start arguing with members of their own kind," said Bell. "It would be a moment when extra armor could help."

Many groups of lizards have bones embedded in their skin called osteoderms. Scientists know the existence of osteoderms in Komodo dragons since at least the 1920s, when naturalist William D. Burden emphasized their presence as an impediment to mass production of leather of dragon. But as the skin is the first organ harvested during the manufacture of a skeleton, scientists do not have much information on how they are shaped or disposed within. the skin.

The researchers were able to overcome this problem by examining the dragons from UT's high-resolution X-ray tomography facility managed by Maïsano. The CTs in the lab are similar to clinical CT scanners, but they use high energy X-rays and finer detectors to reveal the inside of the samples in detail.

Due to the size constraints of the scanner, the researchers only swept the head of the 9-foot-long Komodo adult dragon donated by the Fort Worth Zoo when he died at the age of 19. half. The San Antonio Zoo donated the 2-day-old baby specimen.

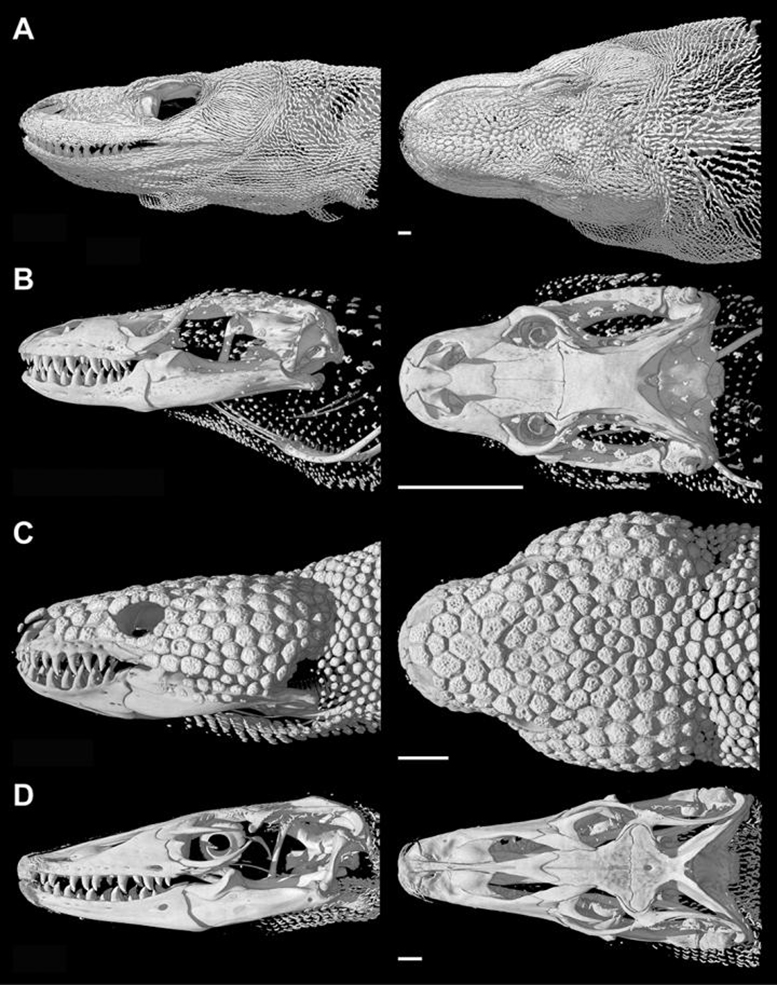

3D reconstructions of different skulls of reptiles and their osteoderms. The left column shows a side view and the right column a top view. The reptiles are: A: Komodo dragon. B: Lizard monitor without ears. C: Monster Gila. D: Asian water monitor. The scale bar is one centimeter. Credit: University of Texas at Austin / Jackson School of Geosciences.

Computed tomography revealed that osteoderms of the adult Komodo dragon were unique among lizards, both in their different forms and in their cover. While the heads of the other lizards examined by the researchers for comparison purposes usually had one or two forms of osteoderms and sometimes large areas, the Komodo had four distinct shapes and a head almost entirely covered with armor. The only areas devoid of osteoderms on the adult Komodo dragon's head are the eye contour, the nostrils, the edge of the mouth and the pineal eye, light sensing organ located on top of the head.

"We were really impressed when we saw it," Maisano said. "Most of the supervising lizards just have these vermiform (worm-shaped) osteoderms, but this type has four very distinct morphologies, which is very unusual in lizards."

The adult dragon that the researchers examined was one of the oldest known Komodo dragons living in captivity at his death. Maïano said that advanced age may partly explain his extreme armor; As lizards get older, their bones can continue to ossify, adding more and more layers of material until death. She added that further research on Komodo dragons of different ages can help understand how their armor develops over time – and could also help identify when Komodos begin to prepare for battle with other dragons.

The National Science Foundation funded the research.

Reference: "Cephalic osteoderms of Varanus komodoensis as revealed by high-resolution X-ray tomography" by Jessica A. Maisano, Travis J. Laduc, Christopher Bell and Diane Barber, June 8, 2019, The anatomical file.

DOI: 10.1002 / ar.24197

[ad_2]

Source link