[ad_1]

Rising sea levels are an unequivocal consequence of climate change. The warmer water expands as the melted land ice flows into the sea. But what fun would it be if the natural world didn’t complicate matters a bit? A number of processes can cause trends observed on different coasts to vary, from ocean circulation to rising or falling land elevation. While we want to quantify each contributor to sea level rise, it’s no surprise that the numbers don’t always add up perfectly.

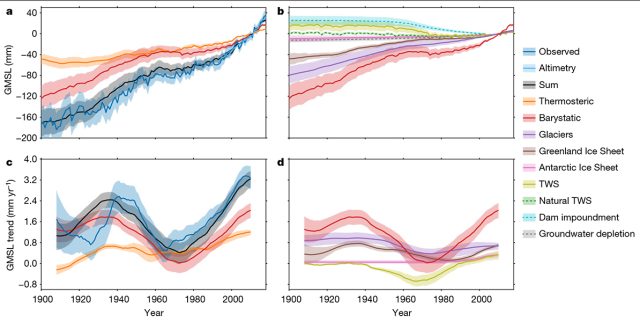

So the researchers turned to a process called ‘budget closing’ – working on adding estimates of ice mass loss, thermal expansion of seawater, and change in storage. water on land and then comparing that to the estimated sea level trends from tide gauges and satellites. . Research has closed the budget for decades, including the era of good satellite data starting around 1990 and going back to around 1960. But in the first half of the 20th century, tide gauges were more sparse, as were observations of glaciers and ocean temperatures. As a result, a lag remained between what we would expect based on the estimated causes of the sea level rise and what we think we saw, based on the estimated sea level rise. There was apparently more sea level rise than we could explain during this time.

Try, try again

Researchers worked on these issues from all angles, solving dataset problems and tackling complications like changes in land elevations. So a team led by Thomas Frederikse at Caltech’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory decided it was time to try again. Frederikse and his colleagues find that the estimates are now consistent since 1900. And that includes a few periods of time when the rates of sea level rise are higher or lower along the way.

By combining all the datasets they could get their hands on, these researchers calculated global and regional estimates from 1900 to 2018. They preserve all error bars by generating 5,000 realizations with possible values selected at random (known under the name of Monte Carlo analysis).

They separate the effect of temperature on the expansion of ocean water volume (“thermosteric” sea level rise) from the factors that add water to the oceans (“barystatic” sea level rise. ). These include the melting of mountain and leaf glaciers in Greenland and Antarctica, as well as the depletion of groundwater resources. In return, there is the construction of dams, which create a storage of surface water on land that did not exist before.

Their estimated average rate of sea level rise for the period 1900-2018 is 1.56 ± 0.33 millimeters per year. The sum of all the sea level change factors is 1.52 ± 0.33 millimeters per year, which is comfortable.

The estimates also agree in the error bars for 1957-2018 and 1993-2018, but these periods see the acceleration of sea level rise, with rates increasing to about 1.78 millimeters per year, then 3 , 35 millimeters per year.

What comes from where

For the first half of the 20th century, water added to the oceans accounts for more than 80% of the total sea level rise, although the construction of dams erodes this number in the second half of the century. Here’s a simpler comparison: Since 1900, melting glacial ice has caused twice as much sea level rise as expansion due to warming.

The two biggest deviations of the 20th century are in the 1940s, when sea level rose a little faster, and the 1970s, when sea level rose a little more slowly. Interestingly, the global temperature trend has varied a bit in the same way, but thermal expansion is not what caused these sea level variations.

In the 1940s, the rise appears to be due to greater ice loss from mountain glaciers and Greenland. The slowdown in the 1970s, on the other hand, corresponded to a peak in the construction of dams on land that “stole” water from the oceans by filling new reservoirs.

When zooming in on individual ocean basins, there are even more factors to consider. Although things like the effects of salinity on seawater volume dissipate around the world average, they become important in a region. There is not enough data on salinity in the early 1900s to go this far anywhere. But even though the number of tide gauge and land rise records varies, the researchers found that the sea level rise budget for each ocean basin matched observations dating back to 1960.

All pools are not the same

There are interesting differences between the basins, with a slower sea level rise in the eastern Pacific than in the South Atlantic, for example. Oddly enough, the sea level trend in the North Atlantic matches the world average despite a strange situation in which competing factors roughly offset each other. The ice caps actually exert a gravitational pull on the surrounding seawater, drawing more water and raising the local sea level. Melting glacial ice, therefore, relaxes this attraction, lowering the local sea level even as the meltwater is discharged into the ocean. The effect reduced the rate of sea level rise in the North Atlantic. But at the same time, the downward movement of the seabed (a relic of the Ice Age) had the opposite effect, bringing in water to fill the deep basin.

Overall, the researchers write: “The closure of the 20th century sea level budget, as demonstrated here, implies that no additional unknown processes, such as large-scale thermal expansion of the deep seabed or loss. of the additional mass of the Antarctic ice sheet, is not needed to explain the observed changes in global sea level. These additional processes had been speculated to explain the non-closure observed in previous studies of the global sea level budget. sea. “

And if we have a good grasp of events so far, it adds some confidence that we understand where and how quickly the water is going to accumulate as the oceans warm and more glacial ice. disappears from the earth.

Nature, 2020. DOI: 10.1038 / s41586-020-2591-3 (About DOIs).

[ad_2]

Source link