[ad_1]

You've heard of moonmoons – that's what scientists want to call the moon's satellite. But are you ready for the ploonets? You'd better be, because we're here to talk about this new hypothetical class of cosmic objects.

That's exactly what it looks like: a kind of cross between a moon and a planet. And the existence of ploonets could help to explain why we have not yet found conclusive exonades.

A new document submitted to the Monthly Notices from the Royal Astronomical Societyand the peer review process is still ongoing: everything is said: Exomoons orbiting a giant, exoplanets the size of Jupiter in other planetary systems could be ejected from their orbit by gravitational interactions .

From that moment, they could become planetary seeds or protoplanets. Or … some ploonets.

"If large exomoonies form around migrating giant planets that are more stable (for example, those of the solar system), the fate of these moons after migration is still the subject of intensive research," the researchers write. .

"This article explores the scenario in which large exomons regular escape after the exchange of angular momentum by the tide with its mother planet, becoming themselves small planets. hypothetical object ploonet. "

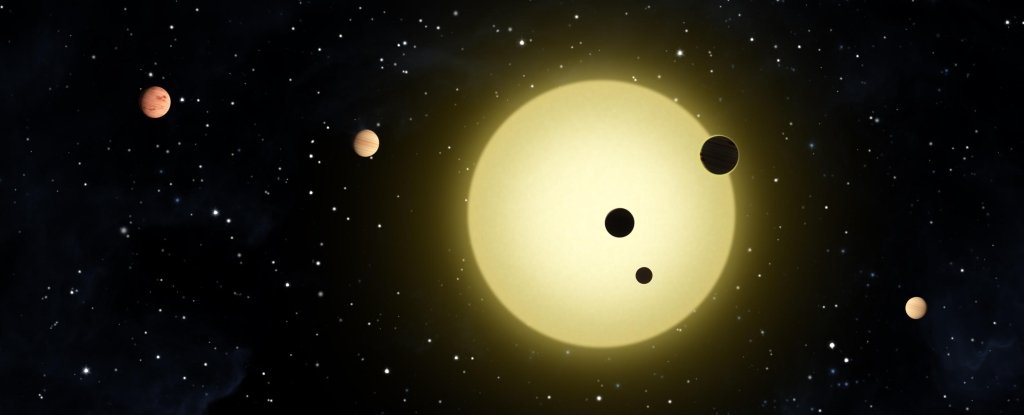

The team ran simulations of a type of planet called Hot Jupiter. These are gas giants of Jupiter that orbit so close to their host star – about the same distance as Mercury – that they are incredibly hot.

Astronomers believe that these planets would have formed much further and migrated inward. Because the conditions close to the star are so hot, most of the gas would have burned instead of growing into a planet.

If they had moons during their migration, this movement towards the interior would generate additional gravitational forces between the moon and the planet.

Mario Sucerquia of the University of Antioquia in Colombia and his colleagues wanted to know what these forces would do. So they conducted a lot of simulations of this migration, where the planet was accompanied by a moon.

They discovered that about 44% of their moons had ended up crushing on their planets and that 6% had been devoured by the star. A very small number – 2% – ended up being completely driven out of the planetary system.

The remaining 48% were separated from their planet, but remained in orbit around the star. These are the ploonets.

Most of the ploonets – about 54% – would be farther away from the star than their parent planet (outer ploonets) and about 14% in an orbit closer to the star (inner ploonets). These may be indistinguishable from a normal planet – so perhaps we have already seen some ploonets without even realizing it.

Many of them – 28% – find themselves in extremely eccentric orbits that cross planets (through planets), and the last 4 percent remain in the same orbit or in an orbit very close to the planet ( neighboring planets). These could interact by gravity with the planet, betraying their presence by playing on the moment when the planet will pass in front of the star.

Moons that end up being destroyed could explain other things we have seen. Debris raised by collision with a planet, for example, could produce interesting ring systems.

If the moon were icy, it could become a swarm of comets evaporating, leaving behind a long tail, like the one we saw orbiting the Kepler-1520 and KIC stars 11026764.

At the end of his life, a board near the star could undergo several simultaneous processes, such as surface sublimation and atmospheric evaporation, blowing the atmosphere so that the planet looks much larger, and projecting materials in space.

Combined with the light curve of the orbit of a planet, it can generate non-periodic and very noisy light curves, like those seen around KIC 8462852, which you may know by the names of Tabby's Star or Boyajian's Star. Pretty wild, huh.

Of course, everything is hypothetical at this point, and the term is not widely used … for the moment.

But it's fascinating the little knowledge we have about the Universe. We could even have ploonets right here in the solar system. We could make one now.

"The force of the Earth's tides is gradually moving the moon away from us at a rate of about 3 centimeters a year," said Sucerquia. New scientist. "Therefore, the moon is effectively a potential planet once it reaches an unstable orbit."

Unbelievable.

The research was submitted to Monthly Notices from the Royal Astronomical Society and is available on arXiv.

[ad_2]

Source link