[ad_1]

Engineers at the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR) are currently working with a replica of InSight Lander to see if they can understand what is blocking the mole of the LG.

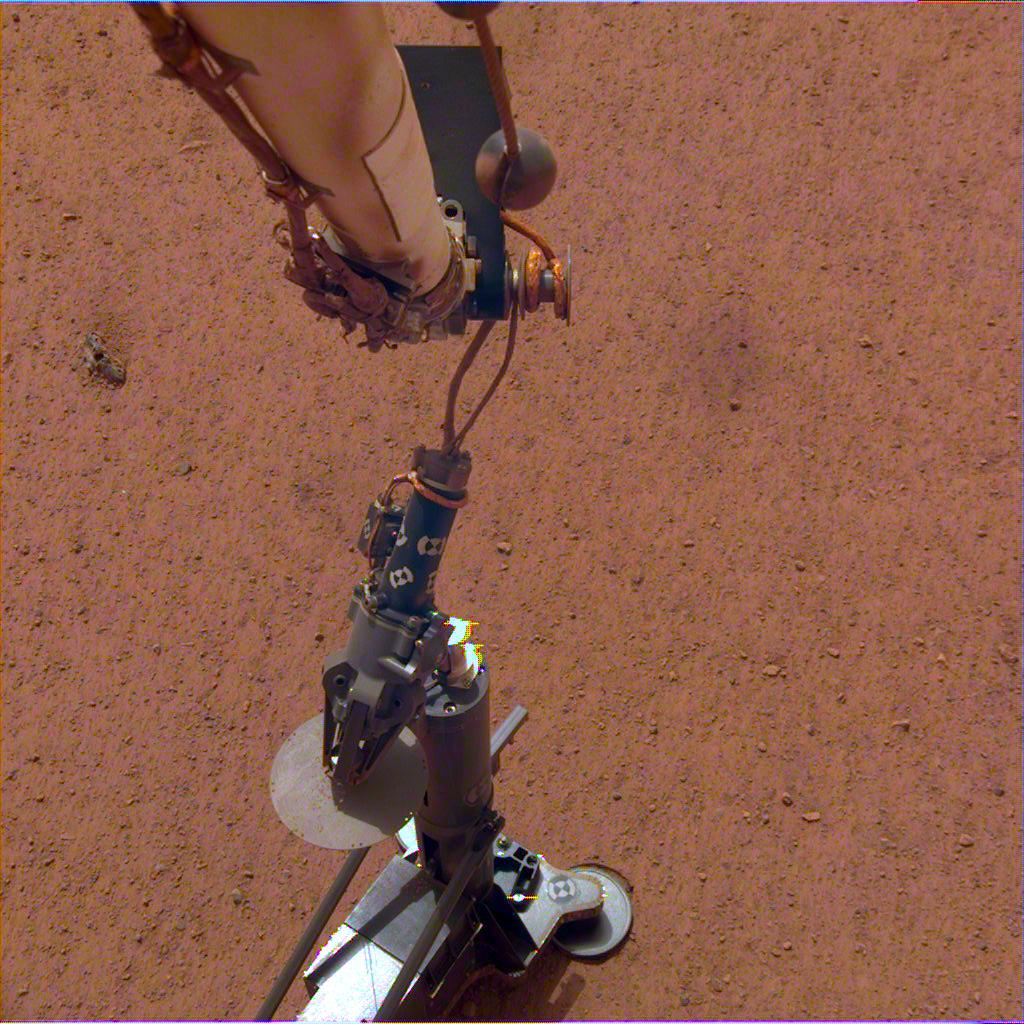

The mole is the abbreviated name of the thermal probe of the lander, which makes its way into the Martian surface. The thermal probe is actually called HP3, or set of physical and thermal properties. It is designed to operate up to 5 meters (16.4 feet) in the ground, where it will measure the heat that flows from the inside of the planet. These measurements will tell scientists a lot about the structure of Mars and the formation of rocky planets.

But as indicated last month, the probe is stuck at about 30 cm (1 ft.)

At first, the engineers thought that the mole had hit a rock. But in a DLR facility in Bremen, they use a probe replica, in a box containing a cubic meter of sand, to study the situation thoroughly. Of course, they hope to find a solution, but it's difficult when you're on Earth and the mole is on Mars.

"There are various possible explanations, to which we will have to react differently."

Matthias Grott, HP3 project manager.

"We are studying and testing various possible scenarios to determine what led to the shutdown of the" mole, "says Torben Wippermann, test manager at the Institute for Space Systems DLR Bremen.

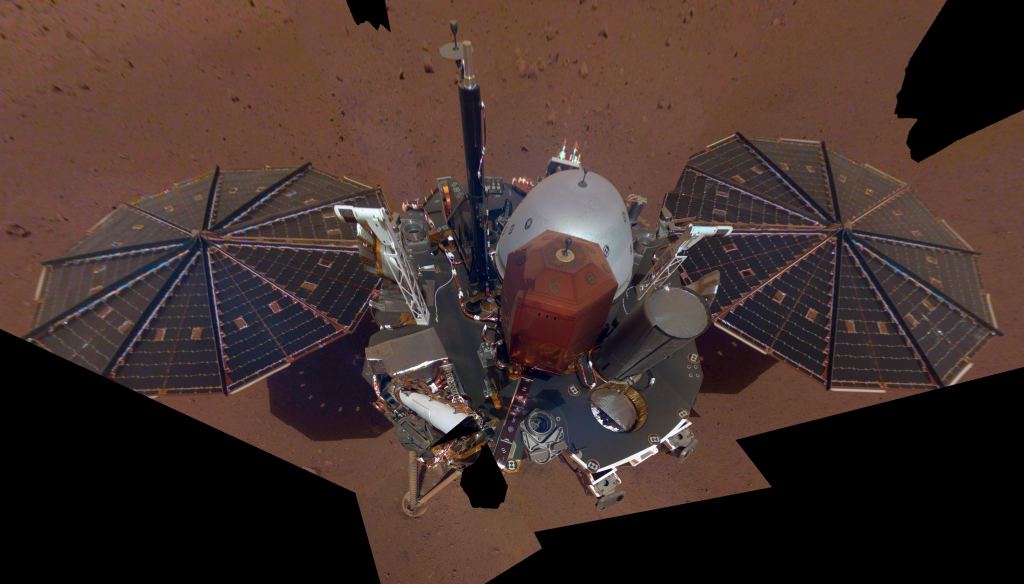

The InSight Lander mission was going well at first. There were surface rocks near the landing site, but the site itself appeared to be free of rocks. The seismometer of the lander, SEIS (seismic experiment for inner structure), was placed on the surface without any problem. But when the mole was placed and began its first hammering operation towards the end of February, problems arose.

At first, the mole was making progress. But then, he hit his first rock. He managed to make his way beyond this rock, but eventually stopped and will not exceed 30 cm deep.

Engineers try to understand what happened, but they do not have much data to continue. They performed a short pounding test with the mole on March 26, and they use the data from this test to better understand the mole's difficult situation. They have at their disposal images, temperature data, radiometer data and recordings made by SEIS during the hammering test.

The central question is, what caused the mole to make such progress in the beginning, then stop in his tracks? A rock is the obvious answer, but maybe not the right one. "There are different possible explanations to which we will have to react differently," says Matthias Grott, a planet scientist and research scientist at HP³.

One possibility concerns the very nature of sand, rather than obstructive rocks. To clear a path to the surface, the mole requires a rub between it and the sand in which it pummels. The engineers think that it is possible that the mole has created a cavity around itself, depriving itself of the necessary friction.

When the mole was tested on Earth, it was tested in a Martian sand analogue and was able to strike up to the ideal depth of 5 meters without a problem. "Until now, our tests have been done with Mars-type sand that is not very cohesive," explains Wippermann. Now they are testing the replica in the Bremen laboratory in a different type of sand.

This type of sand is much more compact, and they want to see if the mole has somehow "dug its own grave" by creating a cavity around it. They will also place 10 cm rocks in a part of the sand to see if this can replicate what the Mars data tells them. When they perform various tests, they record the seismic data and see if certain results match the SEIS data.

"Ideally, we will be able to reconstruct processes on Mars as precisely as possible," Wippermann said in a press release.

Once scientists and engineers discover what is preventing the mole, they can try to find solutions. This is where NASA will be more involved.

The DLR designed and built the HP3 for the InSight Lander mission, but the LG itself was designed and built by NASA. And only NASA has a replica of an InSight lander at a JPL test facility in Pasadena, California. DLR sent a replica of the HP3, or mole, to the JPL. Here, potential solutions involving the undercarriage, the mole, the support structure and the robotic arm of the undercarriage can be tested. It may be that the mole or its supporting structure may be raised, or partially lifted, to solve the problem.

In any case, do not expect a quick fix.

"I think it will take a few weeks before new actions are carried out on Mars," Grott said.

[ad_2]

Source link