[ad_1]

To ward off the effects of aging, one can use retinol creams or play Sudoku.

But maybe we should focus on something completely different.

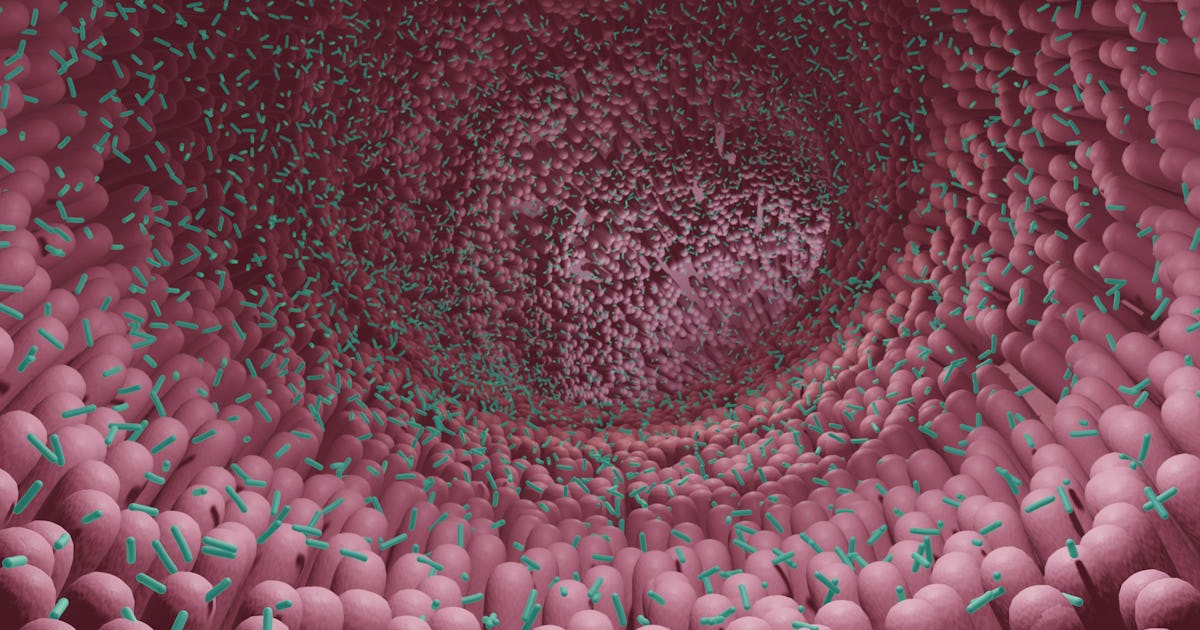

Scientists have known for two decades that the metropolis that is home to billions of bacteria in your womb – the gut microbiome – is also central to mental health, the immune system, and more.

One of the latest gut health studies examines how our microbiome affects aging in mice, using a surprising transplant.

The research, published Monday in the journal Natural aging, reveals that older mice that received gut microbiota transplants from young mice show improved brain function and behavior. This mouse model offers powerful insight into how eating and what populates our stomachs affect the appearance of our brains in old age.

What’s up – The researchers found that when they transplant the microbiota from young mice into the intestines of older mice, the older mice exhibit improved cognitive function. This is the first study to show the correlation between transplantation of a gut microbiome from a younger mouse into an older mouse with improved brain capacity in older mice.

“It was quite mind-blowing.”

In an interview with Reverse, Marcus Böhme, neuroscientist at University College Cork and one of the authors, responded enthusiastically to the research.

“It was really great to see that a complete change in their microbiomes can really excel at such effects on cognitive behavior, like almost resembling the learning performance of young mice, it was quite mind-blowing,” Böhme said.

“Maintaining our gut health is really important for many aspects of normal physiology, especially with age,” says Neil Mabbott, immunopathologist at the University of Edinburgh. (Mabbott did not participate in the study.)

How they did it – Do the words “faecal microbiota transplant” mean anything to you?

Another way to put it is ‘poop transplant’. This is how John Cryan, one of the authors of the article and professor of neuroscience at University College Cork, explains it to Reverse.

They had a group of mice that were three or four months old (similar to the life cycle of a healthy 18-year-old human) and a group of mice that were 19 or 20 months old (similar to a healthy 70-year-old human).

The researchers collected stool samples from the younger mice and transplanted them into the intestines of the older mice to cultivate a similar gut microbiome; bacteria in fecal samples would thrive in their new environment.

And there you have it: the older mice that received the transplant from the younger mice had gut microbiota that resembled that of mice. younger mouse.

And then they administered behavioral tests to the older mice to measure how their brain function might have changed. Notably, they conducted an experiment called the Morris Water Test in which a mouse submerged in a pool of water must walk towards a platform.

Finally, Böhme and his colleagues beheaded their mice and searched their brains, especially the hippocampus which is the seat of spatial learning and memory, to see how their brains had changed in response to the transplant.

Why is this important – FMT won’t become the next anti-aging fad, but this experience tells us more about how taking care of our gut health can help maintain holistic health into old age.

“There are big implications beyond just brain health,” says Catherine guzzetta, a PhD student at University College Cork and author of this article. Guzzetta also artfully notes that knowing the gut health and healthy minds of the elderly can also improve the quality of life of our pets, so that our cats and dogs can continue to enjoy life until old age. advanced.

More immediately, this study could shed light on which aspects of diet are essential for brain health and more so in our golden years.

Dig into the details – In particular, the results of the Morris water maze showed the benefits of this transplant. Older mice that had received the transplant from younger mice performed better in the maze than older mice that had not received the transplant.

Cryan says this behavior is consistent with his team’s findings in the brains of mice. While the transplants gave the older mice the gut microbiomes of the younger mice, in turn parts of their brains appeared younger as well. Specifically, the hippocampus – the region of the brain involved in learning and memory – resembled that of younger mice.

So it seems the gut and the brain are talking to each other, in a way. Cryan says part of this communication comes from the vagus nerve, a “long wandering nerve” that sends signals from throughout the gastrointestinal tract to the brain. But, that is still only part of the bodily cooperation; There remains the question of the mechanism at the origin of these changes.

“I don’t recommend that we do poop transplants.”

And after – Hold on to your gastrointestinal tract: poop transplants are not come to humans in droves quite yet.

“I don’t recommend that we do poop transplants in you and in humans because we have no evidence that it would work in humans,” Cryan explains. (Although FMT is already an effective way to treat infection C. diff in humans.) “But what we have evidence then is that the targeting of microbes, which is in particular or with specific microbes that we can identify with exactly strains, is missing.”

Mabbott agrees that identifying specific bacterial strains that benefit older gut microbiomes is one of the next two crucial steps. “What are the other components of their microbiota that are causing this? And what is the mechanism by which they do this? he says Reverse. “Can we explore specific mechanisms here? This could have very important means of therapeutic intervention here.

“By restoring the microbiome, we target it through this transplantation, we are able to reverse cognition,” says Guzzetta. “It’s mind-blowing.”

Summary: The gut microbiota is increasingly recognized as an important regulator of host immunity and brain health. The aging process causes dramatic alterations in the microbiota, which are linked to poorer health and the fragility of elderly populations. However, there is limited evidence for a mechanistic role of the gut microbiota in brain health and neuroimmunity during aging processes. Therefore, we performed fecal microbiota transplantation from young (3-4 months) or old (19-20 months) donor mice into elderly (19-20 months) recipient mice. Transplantation of microbiota from young donors reversed aging-related differences in peripheral and brain immunity, as well as the metabolome and hippocampal transcriptome of aging recipient mice. Finally, the young donor-derived microbiota alleviated the selective impairments in cognitive behavior associated with age when transplanted into an elderly host. Our results reveal that the microbiome may be an appropriate therapeutic target to promote healthy aging.

[ad_2]

Source link