[ad_1]

The butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa) and thousands of other species of plants and insects are associated with the long-leafed savannah. Credit: Ellen Damschen

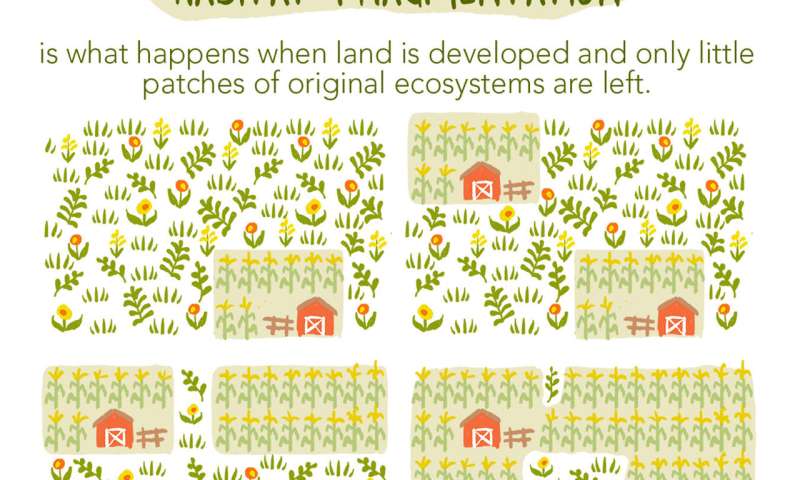

Before the arrival of Europeans in America, the long – leafed pine savannas spread over 90 million acres, from current Florida to Texas and to Virginia. Today, thanks to human impacts, less than 3% of this area remains and what remains exists in fragmented plots, largely isolated from each other.

Yet, hundreds of plant and animal species depend on these savannas, from understory grasses to the gopher turtle, to the endangered red rooster.

Habitat fragmentation is a major threat to biodiversity, not only in the savannas of longleaf pines, but also in the habitats of the planet. A new study published this week [Sept. 27, 2019] in Science demonstrates a promising new strategy in conservation efforts for plant and animal species facing fragmented and declining habitats globally.

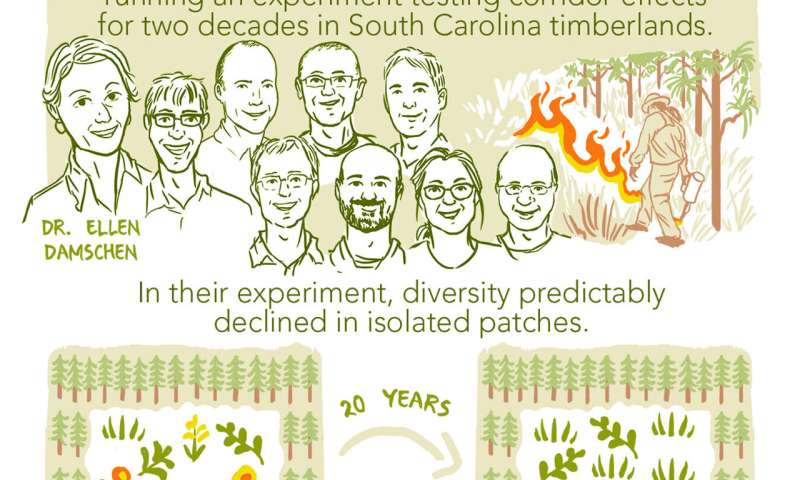

By connecting small patches of restored savannah through habitat corridors in an experimental landscape of the Savannah River site in South Carolina, this nearly 20-year study has shown an annual increase in the number of 39 plant species among fragments over time. and a drop in the number of species that disappear entirely.

"We know that fragmentation and habitat loss are the leading factor in the extinction of species in the United States and around the world," said the senior author of the report. study, Ellen Damschen, professor of integrative biology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. "We need conservation solutions that can protect existing species and restore lost habitat."

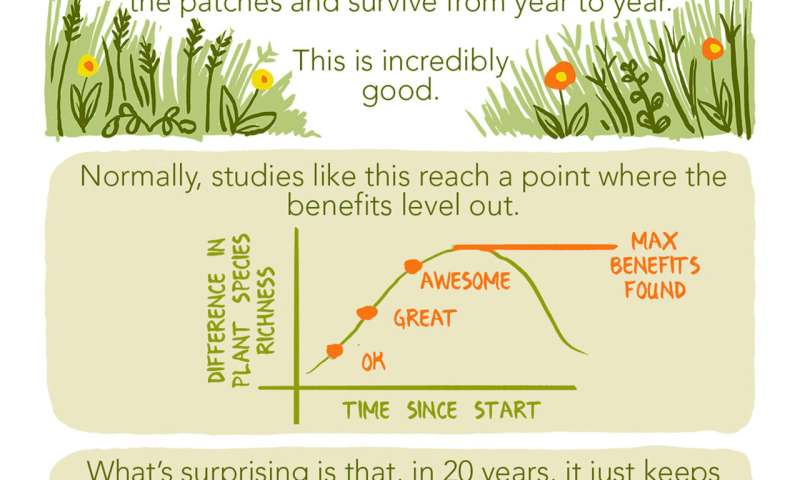

She and her co-author John Orrock, also a professor of integrative biology at UW-Madison, compare the results to an unexpected area: finance. The research team was surprised to see an annual increase of five percent in the number of new species arriving or colonizing longleaf pine fragments connected by a corridor, as well as an annual decline of two to hundred of the number of endangered species.

"Like compound interest in a bank, the number of species increases at a constant rate each year, resulting in a much larger net result over time in habitats connected by a corridor." compared to those who are not, "said Damschen.

During the 18-year study period, this equates to an average of 24 additional species in each connected fragment compared to study control fragments, which were not related by corridors. Each fragment is about the size of two football fields and the corridors that connect them extend over an area of about 500 feet by 80 feet.

-

How corridors affect plant diversity in the long term A four panel cartoon explains the findings of Damschen et al. 2019, Science. Credit: Liz Anna Kozik

-

How corridors affect plant diversity in the long term A four panel cartoon explains the findings of Damschen et al. 2019, Science. Credit: Liz Anna Kozik

-

How corridors affect plant diversity in the long term A four panel cartoon explains the findings of Damschen et al. 2019, Science. Credit: Liz Anna Kozik

-

How corridors affect plant diversity in the long term A four panel cartoon explains the findings of Damschen et al. 2019, Science. Credit: Liz Anna Kozik

"Like any good long-term investment, it builds over time," says Orrock. Neither he, nor Damschen, nor the research team, expected to find an annual rate of increase without any signs of slowing down.

The long-term conservation and restoration study, which is still ongoing, is rare in the ecological world, in part because it controls the area and connectivity of fragmented habitats. Most studies focused only on the size of the habitat.

"From the biodiversity point of view, we know that the habitat zone is important," said Damschen. "But we also need to think about the remaining habitat network and the reconnection of small plots."

For, adds Orrock, "it's not always possible to create more habitat, so the existing habitat connection is another tool in the conservation toolbox".

This study is also unique in its longevity, made possible through funding from the National Science Foundation's (NSF) long-term research program in environmental biology. Most ecological studies focus on one to five years, or on the life cycle of a typical research grant, but the results show that the accumulation of significant results takes time.

"The strength of this long-term study is that small differences in species accumulation rates have a significant long-term impact," said Betsy von Holle, program director at the NSF. "This has major implications for the science of restoration and conservation."

The study also relied on collaboration with the US-Savannah River Forest Service, under the authority of the Department of Energy's Savannah River Operations Office, where fragments and corridors are being restored in the United States. the savanna with long pines. The habitat of the longleaf pine tree has been contracted since the colonial era, as the trees were exploited for timber, tar and turpentine, and lost to the trees. ;urbanization.

"As land managers," says DeVela Clark, Forest Manager at US Forest Service – Savannah River, "we are integrating these long-term studies into our daily savanna restoration work." Ellen and the team research share our belief that research and restoration require a long-term perspective. "

Efforts are also underway in Virginia, the northern limit of the species' historical range, to restore the long-leafed pine savannas, led by The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and the Division of Wildlife. natural heritage of the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation. The UW-Madison study provides results that are at a key point in conservation decisions.

"Restoring plant biodiversity is a race against the clock, especially in the face of accelerating climate change and fragmentation of the landscape," said Brian van Eerden, director of TNC program Virginia Pinelands. "We need the best scientific data from long-term, large-scale studies like this to explain how to connect and manage our conserved lands to ensure that native species have the best chance of survival and prosperity."

The ecosystem of longleaf pines once extended from Texas to Virginia and is home to thousands of plant and animal species. Only 3% of the original habitat remains in isolated fragments today. Credit: Liz Anna Kozik

The restoration of the habitat is now a key priority worldwide. Earlier this year, the United Nations declared 2021 to 2030 United Nations Decade for the Restoration of Ecosystems, in the hope of eliminating excess greenhouse gas trapping heat; improve food security and freshwater supply; and protect critical human and animal habitats.

"Experimenting on the consequences of habitat loss and fragmentation at realistic scales is incredibly difficult because, when you look at a real landscape, so much happens at the same time," says Damschen. "You need a solid experience that isolates these independent factors – such as size, connectivity, proximity to a habitat – on a scale relevant to conservation and on a significant time scale.

"We have this opportunity for 20 years."

Landscape-level habitat connectivity is essential for species that depend on longleaf pine

E.I. Damschen el al., "Continuous accumulation of plant diversity through habitat connectivity during an 18-year experience" Science (2019). science.sciencemag.org/lookup/… 1126 / science.aax8992

Quote:

Scientists have connected fragments of pine savanna and new species that continue to appear (September 26, 2019)

recovered on September 26, 2019

from https://phys.org/news/2019-09-scientists-fragments-savanna-species.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair use for study or private research purposes, no

part may be reproduced without written permission. Content is provided for information only.

[ad_2]

Source link