[ad_1]

Scientists have used a form of non-invasive electrostimulation to improve the working memory of the elderly, giving the 70-year-old the thinking skills of their 20-year-old self, at least temporarily.

Working memory is the cognitive resource responsible for decision-making at all times. It allows us to keep and access useful and relevant information, such as names, phone numbers and where we have placed things.

Unfortunately, this resource decreases with age, and not only in people with significant cognitive impairment, such as dementia, but also in healthy people who also experience the normal neurocognitive effects of aging.

The good news is that this decline in working memory does not seem to be permanent.

"Age-related changes are not immutable," said neuroscientist Robert Reinhart of Boston University. The Guardian.

"We can bring back the higher memory function you had when you were much younger."

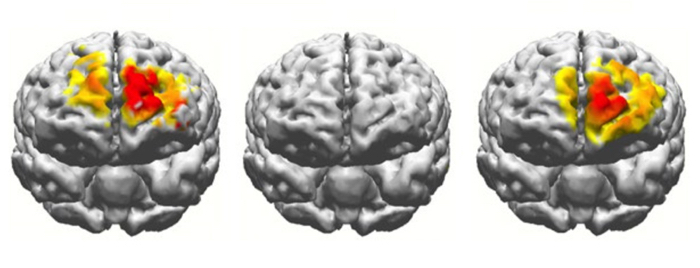

(Reinhart Lab / Boston University)

(Reinhart Lab / Boston University)

Above: EEG representations of working memory (from left to right) in a 20-year-old without stimulation, elderly without stimulation, elderly with stimulation.

In his new research, Reinhart administered a non-invasive electric current to elderly and young people to determine its impact on the performance of their working memory.

As part of the experiment, 42 young participants (aged 20 to 29 years) and 42 older adults (60 to 76 years) had a memory task in which they had to identify the differences between the images presented.

Predictably, given what we know about work memory deficits that accumulate with age, older participants were significantly slower and less accurate than younger adults. Age is only one way of explaining this contrast.

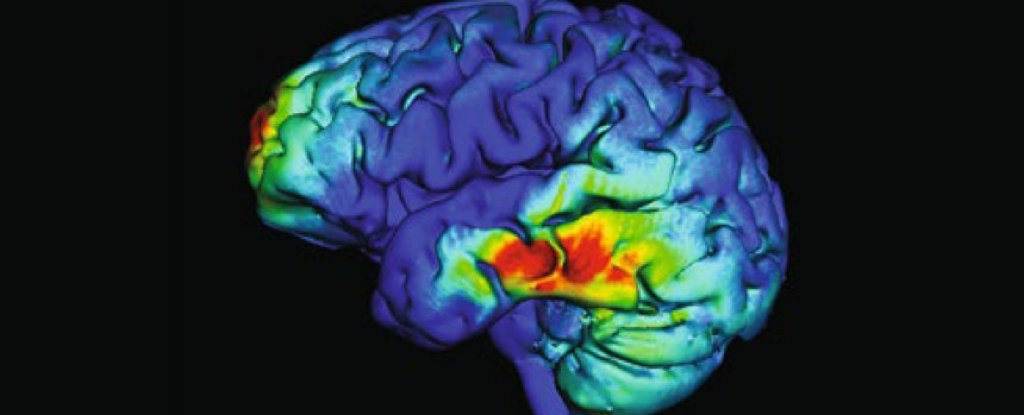

Another is that some of our brain's rhythms fail to coordinate successfully with older people; these rhythms help different parts of the brain relay information and memories.

Neuroscientists currently believe that slow, low-frequency rhythms called theta must synchronize with faster, higher frequency gamma rhythms located between the prefrontal and temporal areas of the brain for our working memory to work effectively.

This synchronization is called phase-amplitude coupling (PAC), but if it seems to decrease with age, a form of electrostimulation called transcranial AC stimulation (tACS) seems to resynchronize these uncoupled brain circuits.

In the study, electroencephalographic (EEG) measurements of brain activity of participants showed greater synchronization in young adults.

"The results suggest that theta-gamma PAC in young adults is behaviorally significant, predictive of the subsequent success of working memory," the authors explain in their article.

But that's not all. When researchers used a targeted form of tACS stimulation called HD-tACS on the participants, these synchronization problems disappeared.

"HD-tACS seemed to eliminate age-related alterations in working memory accuracy," the researchers write.

"This behavioral improvement was sufficient to eliminate the initial group difference in terms of accuracy of working memory, with older adults after stimulation having an average level of precision statistically indistinguishable from that of younger adults at baseline."

With only 25 minutes of stimulation technique, this technique improved the performance of older participants in the memory task at the younger adult level, and the effects lasted up to 50 minutes after the end of the stimulation.

The researchers said these improvements were a reflection of the restored theta-gamma coupling in the EEG readings of older participants, and that the benefits should also extend to young people, not just older people.

In another test, young adult participants who performed poorly during the working memory exercise received HD-tACS stimulation, which also improved their results.

"We have shown that the underperforming, much younger and in their twenties, could also benefit from the same kind of stimulation," Reinhart said in a statement.

"We could improve their working memory even if they were not in their sixties or sixties."

Although much research is needed before understanding the mechanisms involved – let alone being able to develop research-based treatment – the results could be a major step forward in reducing the working memory deficits of the world's population. aging.

"The results of the study raise interesting questions about brain activity that supports working memory and its mechanism of action," says neuroscientist Nir Grossman of Imperial College London, who did not participate in the research.

"Regardless of the brain activity and mechanism involved, the continuous improvement in working memory observed after the short stimulation period can potentially evade potential future research and rehabilitation."

For Reinhart, the next steps are to examine how repeated doses of stimulation can affect people and to try to determine how the mechanisms work in animal models.

With time and other positive results, the researchers say that it is possible that we examine a whole new spectrum of research and treatment options.

"It is wild to think that we can target the electricity of a brain circuit in the same way that we would target a chemical neurotransmitter in the brain," said Reinhart.

The results are reported in Nature Neuroscience.

[ad_2]

Source link