[ad_1]

data-src = "https://scx2.b-cdn.net/ gfx / news / hires / 2019/11-scientiststr.jpg "data-sub-html =" This Rhacophorus bimaculatus The frog, a native of the Philippines who lives in misty areas under waterfalls, is one of many species of frogs threatened by the deadly fungus of the chytrid. Credit: Rafe Brown & amp; Jason Fernandez ">

This Rhacophorus bimaculatus The frog, a native of the Philippines who lives in misty areas under waterfalls, is one of many species of frogs threatened by the deadly fungus of the chytrid. Credit: Rafe Brown & Jason Fernandez

Be it habitat loss or climate change, amphibians around the world face immense threats to their survival. The chytrid fungus, a mysterious pathogen that kills amphibians by disrupting the delicate balance of moisture maintained by their skin, decimates frog populations around the world.

"Amphibians are already one of the most endangered groups on the planet and this fungal disease further threatens their biodiversity," said Erica Bree Rosenblum, associate professor of science, policy and management at the University of California. environment at the University of California at Berkeley.

Thanks to advanced genetic testing and hundreds of frog skin samples, Rosenblum, Berkeley graduate student Allison Byrne, and an international team of collaborators created the most comprehensive map ever made. analogous to different strains of viruses like the flu – have infected frog populations worldwide.

Some of these genetic variants are more lethal than others, too, knowing that their current geographical distribution is essential to prevent the spread of the disease, the researchers said. The investigation also uncovered a brand new genetic lineage of the fungus, which seems to come from Asia and could be the oldest variant ever discovered.

"An invisible aspect of globalization is that when we transport plants and animals, we transmit their diseases, which can have truly devastating consequences," said Rosenblum. "If we know which lines, where, we can better predict the results of conservation, because some of these lineages are really deadly and others less so."

The study appears online the week of September 23 in the newspaper Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

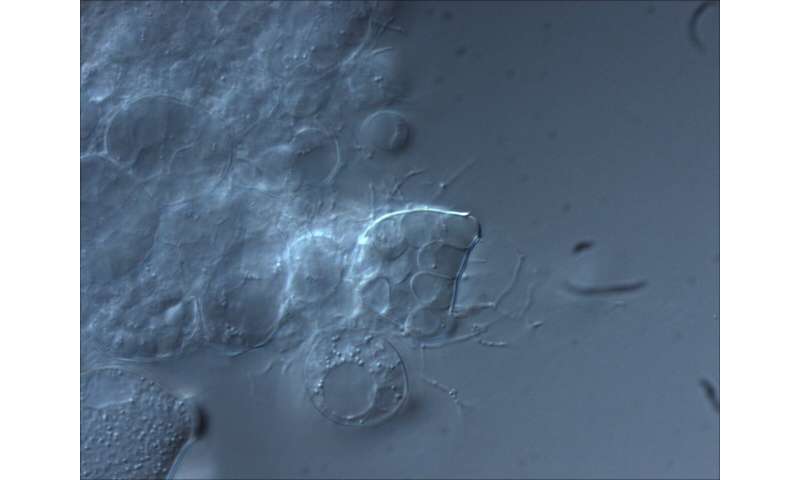

The chytrid fungus, bearing the scientific name Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, infects the skin of frogs and disrupts the ability of the animal to properly maintain moisture and electrolyte balance. Credit: Erica Bree Rosenblum

Tracking an emerging pathogen

"Chytrid" is the name of not one, but about 1000 species of different mushrooms, most of which are harmless detritivores that spend their lives chewing dead and decaying organic matter. The variety that kills frogs, known as Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, was not discovered until the late 1990s, when scientists were desperately searching for the source of the frightening death of frogs that had been growing worldwide since 1970s.

Although researchers now have a culprit, there are still many unknowns about this enigmatic disease: some species of frogs, such as bullfrogs, are not affected by the fungus, while for others, exposure to mushroom causes almost certain death.

Scientists are also unclear about the origins of chytrid species that kill frogs. It may have been hiding in a corner of the planet for thousands of years and has only attracted worldwide attention when the global frog trade for their meat and for experiments in laboratory has exposed new populations to the pathogen. On the other hand, it is possible that a recent genetic mutation of the fungus suddenly made it more virulent, said Rosenblum.

"Not all amphibian species are equally vulnerable, not all strains of the fungus are equally lethal, and many questions remain unanswered about the disease." Do humans move it? the different strains assemble, mix and become even more deadly? "Rosenblum said. "It's like a murder mystery that we are trying to solve."

To find the answers, researchers often turn to genetic testing to "go under the hood" of a disease, using DNA signatures to map the different variants of a pathogen and trace them back to # 39 at their source. However, complete genome sequencing of the chytrid fungus is notoriously difficult because it requires large samples of the fungus that must be grown and grown in the laboratory and sometimes involves killing the infected frog.

In the present study, Byrne borrowed technologies derived from medical research to create a new genetic test to determine the variant of the fungus that a frog uses only a skin buffer. Rather than sequencing the entire genome, the test focuses only on key DNA extracts to distinguish one variant from another. Since it relies only on small extracts, it requires much less DNA.

"People used the Q-tip cotton swab just to check if the pathogen is present or not, but we can now use the same buffers to determine the genetic details of the fungus," said Rosenblum. "There are literally hundreds of thousands of these swabs in freezers all over the world, and now, from these skin swabs, we can not only determine that this frog is infected, but in particular what lineage of the disease is that. Is it the same line that infects the frog living next door, in another country or in the world? "

This delicate tree frog commonly referred to as "Rain Rain" is only found among the understorey tree leaves of the tropical rainforests of the Philippines. This frog species has also been tested positive for the chytrid fungus. Credit: Rafe Brown & Jason Fernandez

Mapping a mushroom through space and time

Rosenblum and Byrne have collaborated with collaborators around the world to analyze 222 mushroom samples from 24 countries. These samples included skin samples collected in the field, as well as samples from preserved museum frogs, the oldest of which was in 1984.

"I think something that most passionates our people is going back in time with these museum specimens," Byrne said. "You can take an amphibian in a jar, collected a hundred years ago, rub it and start now to really give an idea of the spread of these lines."

The analysis revealed the distribution of the four known lineages around the world and brought to light a brand new lineage that seems to be native to Asia. He also showed how, in many places, different lines of the pathogen seem to coexist. This perspective is frightening because recent laboratory work has suggested that, like many human viruses, different lines of the pathogen can mix and become more deadly.

Researchers believe that policies limiting the transport of frogs and other animals across international borders could help prevent the spread of the disease. For example, restrictions on salamander imports from Europe have so far prevented a related species of fungus, Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans, from entering the United States.

"We are finding that political actions can slow down or prevent the spread of these diseases," Byrne said. "I think there may be a little complacency about the fact that this chytrid is basically everywhere, but now we know that they are not all identical, the risks depend on the lineage, lineage, and then lineages, you could have many unintended consequences. "

Allison Q. Byrne et al., "Cryptic diversity of a widespread global pathogen reveals increased threat to amphibian conservation" PNAS (2019). www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1908289116

Quote:

Scientists hunt down frog killer mushroom to curb its spread (23 September 2019)

recovered on September 24, 2019

at https://phys.org/news/2019-09-scientists-track-frog-killing-fungus-curb.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair use for study or private research purposes, no

part may be reproduced without written permission. Content is provided for information only.