[ad_1]

Volta’s electric eels can congregate in groups, working together to lock up smaller fish in shallower waters, according to a new study. Then, smaller groups of about 10 eels attack in unison with high voltage shocks.

Electric eels have long been viewed as solitary predators, preferring to hunt and kill their prey on their own by sneaking up on unsuspecting sleeping fish at night and shocking them into subjugation. But according to a recent article published in the journal Ecology and Evolution, there are rare circumstances in which eels instead use a social hunting strategy. Specifically, the researchers observed more than 100 electric eels in a small lake in the Brazilian Amazon River basin, forming cooperative hunting groups to capture small fish called tetras.

“This is an extraordinary find,” said co-author C. David de Santana, of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. “Nothing like this has ever been documented in electric eels. Group hunting is quite common in mammals, but it is actually quite rare in fish. There are only nine other species of fish known to do that, which makes this discovery really special. “

Electric eels are technically fish with a knife. The eel produces its characteristic electrical discharges – both low and high voltage, depending on the purpose of the discharge – via three pairs of abdominal organs composed of electrocytes, located symmetrically along both sides of the eel. The brain sends a signal to the electrocytes, opening the ion channels and briefly reversing the polarity. The difference in electric potential then generates a current, much like a stacked plate battery.

Douglas Bastos

This is not the first time that researchers have made surprising discoveries about electric eels. For example, 19th century physicist Michael Faraday conducted several experiments with electric eels in 1838. He noted that he only felt light shocks because the water dissipated the shocks so quickly. Vanderbilt University biologist and neuroscientist Kenneth Catania is one of the most prominent scientists studying electric eels today. He discovered that creatures can vary the degree of voltage in their electric shocks, using lower voltages for hunting purposes and higher voltages to stun and kill prey. These higher voltages are also useful for tracking potential prey, such as how bats use echolocation.

And in 2016, Catania reported evidence to support Alexander von Humboldt’s 1800 account of how the Venezuelan natives of the time used wild horses to attract and trap electric eels (“horse fishing” ). The stomping and snorting of horses in shallow water favored by electric eels caused the eels to leap and stun the horses with a series of high voltage electric shocks as a defense mechanism. Once the eels were exhausted, the natives could easily catch them using small harpoons on strings.

For centuries, naturalists rejected Humboldt’s account, because no one since then had noted such behavior – until Catania spotted eels in his lab reacting much like Humboldt’s description to the sight. of the net used to transfer the eels from their cages to the chamber used by Catania for the experiments. He carried out experiments with LEDs mounted on a false alligator head (equipped with a conductive tape to visualize the discharges). The eels aggressively attacked the false alligator head, as described by Humboldt. Catania believes the answer comes in certain conditions, such as when eels are stranded in small bodies of water with the sudden onset of the dry season.

Until 2019, scientists believed that the electric eel was the only species of its particular genus. It was the year of Santana’s publication of an article effectively tripling the number of known species of electric eels. Among these was the subject of the current article: Volta’s Electric Eel (Electrophorus voltai).

“An individual of this species can produce a discharge of up to 860 volts, so in theory, if 10 of them discharged at the same time, they could produce up to 8,600 volts of electricity,” said de Santana. “That’s about the same voltage needed to power 100 light bulbs.” He has been shocked several times in the field and finds that, if it lasts only a fraction of a second, a shock can still cause painful muscle spasms.

DA Bastos et al., 2021

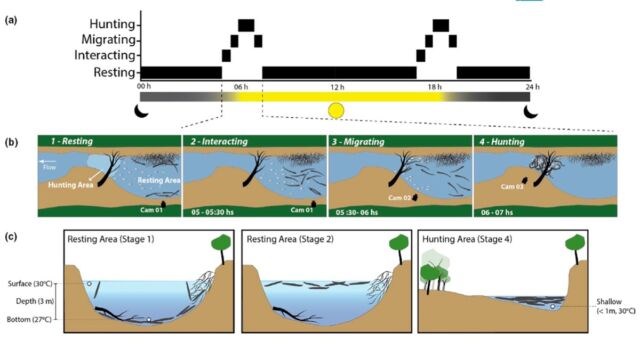

De Santana and his co-authors first noticed the unusual behavior of group hunting during a field expedition in 2012 to explore the diversity of fish in the Iriri River, when the team member ( and co-author) Douglas Bastos found a small lake filled with over 100 electric vehicles. eels. A second expedition in 2014 found a similarly sized group in the same location, and the team eventually logged around 72 hours of continuous observation, recording the behavior of the eels.

Most of the time, the eels were just hanging out at the bottom of the lake, sometimes coming up to the surface to breathe. But the eels became active at dusk and dawn. De Santana’s team noted how eels would work together to gather schools of grouse in densely populated areas in shallow water, swimming in a large circle to create the equivalent of a corral. Then the eels spit in small hunting groups of about 10 eels, circling the grouse ball and stunning the small fish with synchronized high-voltage discharges. This made it very easy to catch the stunned grouse.

“This is the only place where this behavior has been observed, but at the moment we believe that eels probably appear every year,” de Santana said. “Our initial hypothesis is that this is a relatively rare event that only occurs in places with a lot of prey and enough shelter for a large number of adult eels.” If the behavior was trivial, he thought, it would have manifested itself in their conversations with the locals.

De Santana and his team will continue to investigate this unusual behavior; they hope to perform direct measurements of the synchronized discharges on their next expedition. And they started a citizen science program called Project Poraque to track down additional packs of electric eels in the area. The team will also collect eight to ten adult eels and bring them to a laboratory in Germany, to better study them under more controlled conditions.

DOI: Ecology and Evolution, 2021. 10.1002 / ece3.7121 (About DOIs).

Ad image by L. Sousa

[ad_2]

Source link