[ad_1]

Five public research institutions in France announced a three-month moratorium on prion research this week, following a newly identified case of prion disease in a retired laboratory worker.

If the case turns out to be linked to laboratory exposure, it would be the second case identified in France. In 2019, another lab worker in the country died of prion disease at the age of 33. His death came about nine years after accidentally pricking his thumb with forceps used to manipulate frozen slices of humanized mouse brains infected with prions.

Let’s pray and sickness

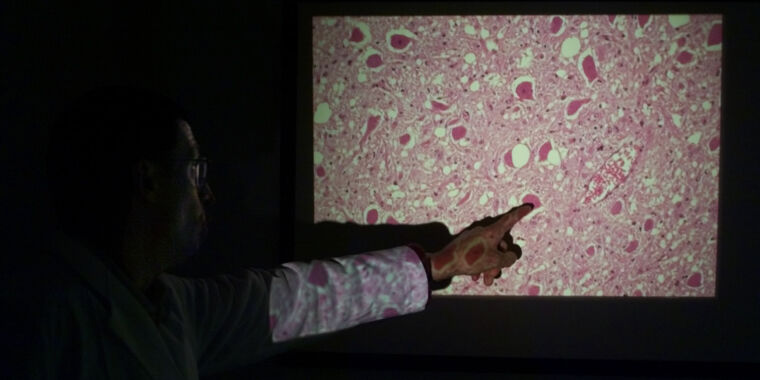

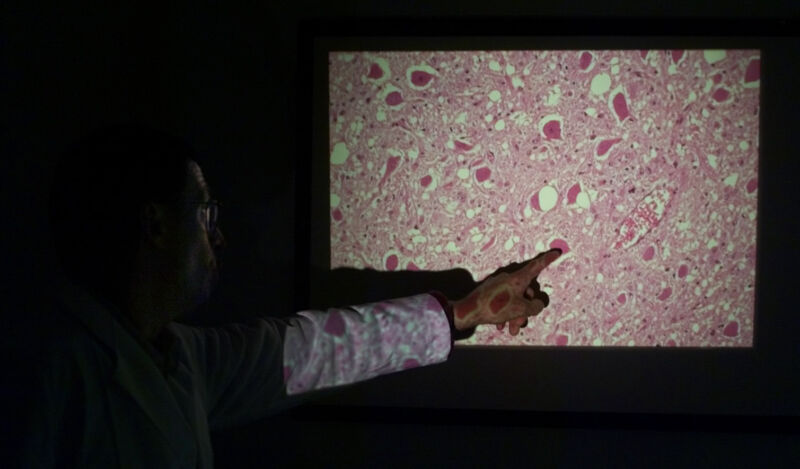

Prions are misfolded and distorted forms of normal proteins, called prion proteins, that are commonly found in human cells and other animal cells. It is not yet clear what prion proteins normally do, but they are readily found in the human brain. When a misfolded prion enters the mix, it can corrupt the normal prion proteins around them, causing them to fold too, clump together, and corrupt others. As the corruption spreads through the brain, it causes damage to brain tissue, eventually causing small holes to form. This makes the brain appear spongy and is the reason why prion diseases are also called transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs).

Outward symptoms of TSEs can include rapidly developing dementia, painful nerve damage, confusion, psychiatric symptoms, difficulty moving and / or speaking, and hallucinations. There is no vaccine or treatment for TSEs. They often progress rapidly and are always fatal.

The most common type of TSE in humans is Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), which comes in two forms: “classic” and “variant”. The classic form strikes about one in a million people in the United States and other countries, and patients typically die within a year of onset of symptoms. In about 85% of patients with classical CJD, the disease is sporadic. That is, there is no clear explanation of what triggered the protein misfolding. In about 5% to 15% of cases, the disease is considered inherited, related to a family history of CJD or a prion protein mutation related to misfolding. In extremely rare cases, classical CJD can also be acquired, usually through medical procedures contaminated with prions, such as a corneal transplant.

The variant CJD, on the other hand, is an infectious type, and it is often associated with bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), a.k.a. ‘mad cow’ disease. People can contract variant CJD by eating meat contaminated with prions, which appeared to be the case during a large outbreak of BSE in cattle and a variant of CJD in people in the Kingdom. United during the 1980s and 1990s. It also seems possible to develop a variant of CJD through wounds infected with prions, and prions could even spread in aerosols – at least the researchers have shown that this is was possible in mice. Once exposure occurs, the variant CJD tends to incubate for about 10 years. That is, symptoms appear about a decade after exposure to the prion.

Emilie Jaumain

It is important to note that the classic and variant forms of CJD have distinct clinical and pathological features. On the one hand, classical CJD tends to affect the elderly (the median age of death is 68 years), while the variant form tends to strike earlier (the median age at death is 28 years old). ). Classic CJD can start with memory problems and confusion, while variant CJD can start with psychiatric symptoms and painful nerve damage.

The variant CJD was the obvious cause of 2019 prion disease in the young lab worker, named Émilie Jaumain. In May 2010, Jaumain, 24, was working in a prion laboratory at the French National Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment (INRAE) when she tragically stabbed her thumb, piercing a double layer of latex gloves and drawing blood. “Emilie started to worry about the accident as soon as it happened and told every doctor she saw about it,” her widower, Armel Houel, told Science Magazine.

According to a case report of his illness and death published in the New England Journal of Medicine last year, Jaumain first developed symptoms in November 2017, about 7.5 years after the accident. Symptoms began as a burning sensation in his right shoulder and neck, which worsened and spread to the right half of his body over the next six months. In January 2019, she became depressed and anxious and suffered from memory impairment and visual hallucinations. The muscles on the right side of his body stiffened. According to an association created on behalf of Jaumain to promote laboratory safety, she was diagnosed with variant CJD in April 2019 and, before her death in June, lost the ability to move and speak. Postmortem analysis included in the NEJM case report confirmed the diagnosis of variant CJD.

Researchers cannot entirely rule out the possibility that Jaumain developed a variant of CJD after eating contaminated meat. However, the authors of the NEJM report noted that the last similar case of variant CJD in France died in 2014. The authors concluded that the risk of developing variant CJD in France in 2019 was “negligible or non-existent. “.

Laboratory safety

The authors also note that occupational cases of variant CJD are not unheard of. “The last known Italian patient with variant CJD, who died in 2016, had occupational contact with brain tissue infected with BSE, although subsequent investigation did not reveal any laboratory accidents,” wrote the authors.

So far, little is known about the new case in France that triggered the moratorium this week. In a joint statement announcing the moratorium, research institutions said it was not yet known whether the retired researcher, who also worked at INRAE, had variant or classic CJD.

“The suspension period put in place from this day on will make it possible to study the possibility of a link between the observed case and the person’s former professional activity and to adapt, if necessary, the preventive measures in force. in research labs, “the joint statement, released Tuesday, reads.

According to a report in Science magazine, Jaumain’s family has filed both criminal proceedings and an administrative legal action against INRAE. The family’s lawyer told the magazine that she was not properly trained to safely handle dangerous prions, that she was not wearing wire mesh or surgical gloves, and that she did not have immediately soaked the thumb in bleach, which the lawyer said should have been done.

Decontamination of prions is notoriously difficult. The World Health Organization recommends decontaminating waste by soaking it in a high concentration of bleach for an hour, then putting it in an autoclave (a steam and pressure sterilization machine) at or at- above 121 ° Celsius (~ 250 ° Fahrenheit) for one hour. That said, for skin punctures, the WHO suggests that people should “gently encourage bleeding” and wash the wound with soap and water.

French investigators have identified 17 other laboratory accidents involving prions over the past decade in the country, five of which involved cuts or stabbing, Science noted. Some labs have said they have improved safety in the light of Jaumain’s death, for example by using plastic tools that are less sharp than metal ones and using cut-resistant gloves.

[ad_2]

Source link