[ad_1]

It’s hard to believe that in the middle of summer, I write about the stars and winter constellations. But there is a good reason.

If you’ve ever been outside on a winter night, you’ve undoubtedly enjoyed the sight of the brightest stars and constellations of the year. But you probably also cut your viewing session short for a good reason: the cold temperatures. Many astronomers have been affected by freezing, sometimes freezing, conditions. Too bad, because there are so many glorious views that the winter sky offers us. As I have often wished to be able to enjoy the wonders of the winter sky in a warmer climate.

Indeed, it would be good to contemplate the winter wonders from a place in the Caribbean or south of the equator. But for those of us who just can’t afford to experience such mild localities in January or February, I offer a simple fix: this week, set your alarm clock for 4:30 a.m.

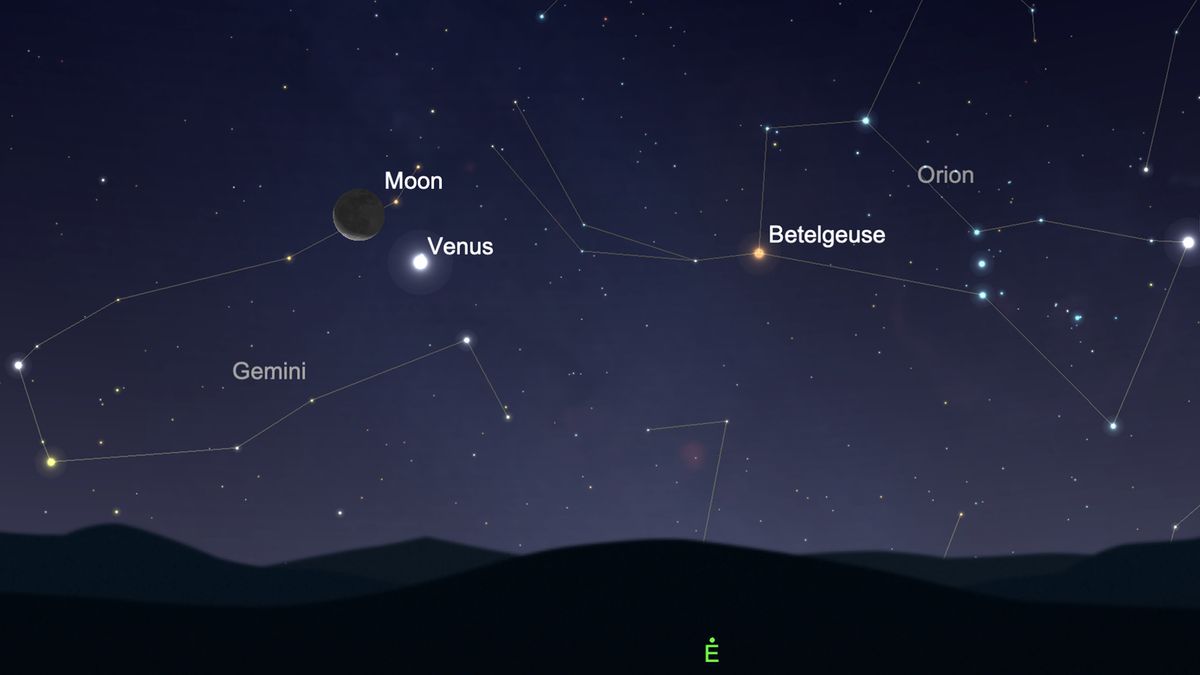

And here’s something to get you out of bed; call it a bonus if you will. Early on Saturday morning (August 15), the dazzling planet Venus will shine within 4 degrees at the bottom right of a thin crescent moon, an eye-catching celestial scene!

Related: Best Night Sky Events for August 2020 (Stargazing Maps)

Venus will be in conjunction with the moon – meaning the two objects share the same celestial longitude while coming close together – on Saturday at 9:01 a.m. EDT (1301 GMT), according to NASA.

For sky watchers in New York, the sun will rise at 6:06 a.m. local time, so the pair can be difficult to see at the time of conjunction. However, early risers and night owls can still observe the close approach for a few hours before daylight. The moon rises over New York at 2:06 a.m., followed by Venus at 2:33 a.m. local time.

Winter stars, without the cold

If you step outside at a rather unholy hour, you will be transported to heaven welcoming you on a typical early January evening. Direct your attention west-northwest and you’ll see the Summer Triangle prepare to leave the scene; around the time when the night started, he appeared almost directly above.

Hovering over Polaris, the Northern Stars are the five bright stars that form a zigzag row, somewhat resembling the letter “M” – the constellation Cassiopeia, Queen of Ethiopia. But when darkness had just started to fall about eight hours earlier, it looked like a letter “W” hovering low above the northeast horizon.

But the real spectacle can be seen towards the southeast, where the sky is dotted with the bright lights of winter: the constellations of Orion, Taurus and Gemini; the shining stars Betelgeuse, Rigel and Capella; the magnificent star clusters of the Pleiades and Hyades as well as the great Orion nebula. They all said goodbye to our evening skies in April, as the last winter cold wore off and was replaced by milder spring temperatures.

And now they’re all back to enjoy them again – and this time you probably won’t need much more than a light jacket or sweater to avoid the morning chill. Now you can pull out your binoculars or telescope and enjoy these prominent star patterns without having to worry about the possibility of getting frostbite or weak wind chill factor.

Vying for your attention

Even for a casual observer, these bright stars and constellations are hard to miss. I remember I was a very young boy who spent the summers with my aunt and uncle on Long Island. In August, one day of each year, a great fishing trip was planned on a boat that left the city of Babylon at dawn. My dad took me with him, where I joined other uncles and cousins on a day-long adventure at sea.

But for me the most memorable part of the trip was always at the start when we loaded the station wagon with our gear in the dark before dawn. I couldn’t help but notice how dazzling and bright the stars were at this early hour. I didn’t know much about constellations at the time, but there’s no doubt in my mind that without knowing it I was probably admiring Orion and his sequel.

A signal that cooler days are on the way

Another object making its first appearance since it was last seen disappearing under the glare of the sun last spring is the brightest star in the night sky, Sirius. In July and early August, Sirius glows invisibly during the day. Legend has it that the sunlight combined with the light of the night’s brightest star is what caused the extreme heat often felt at this time of year.

Since Sirius is the brightest star in the constellation Canis Major the Big Dog, and hence was known as the “Dog Star”, the spell of oppressive summer weather has come to be known as the “Days of dog”. Dog days officially end on August 11 with Sirius’ “heliacal rise” – his first appearance in the twilight morning sky, just before sunrise.

So no matter what the temperature is in your area, this appearance of Sirius – a star we most associate with the winter season – now rising just before the sun, is a subtle reminder that the hottest time of the year. is now behind us and the promise that a change to cooler weather will only be a matter of a few weeks.

Four minutes make it all possible

The reason we can see stars associated with the winter season in August is because the Earth does a full rotation on its axis not in 24 hours, but rather four minutes away: in 23 hours 56 minutes. As a result, the stars rise four minutes earlier each day than the day before.

And those four minutes can quickly add up.

After 30 days, a star rises two hours earlier. When this schedule is expanded to cover an entire year, it represents 24 hours. So this cycle repeats after one year. Five months from now, in mid-January, the night sky that we now see at 4:30 a.m. will be visible at 5:30 p.m. (in places where daylight saving time is observed falling, that’s actually a difference of 11 hours and not 10 hours).

Of course, by mid-January the average nighttime ambient air temperatures across the country will be around 40 degrees Fahrenheit (22 degrees Celsius) cooler than they are now, which is why it’s so much cooler. comfortable to enjoy the stars of winter … summer!

Joe Rao is an instructor and guest speaker at the Hayden Planetarium in New York. He writes on astronomy for Natural History magazine, Farmers’ Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

[ad_2]

Source link