[ad_1]

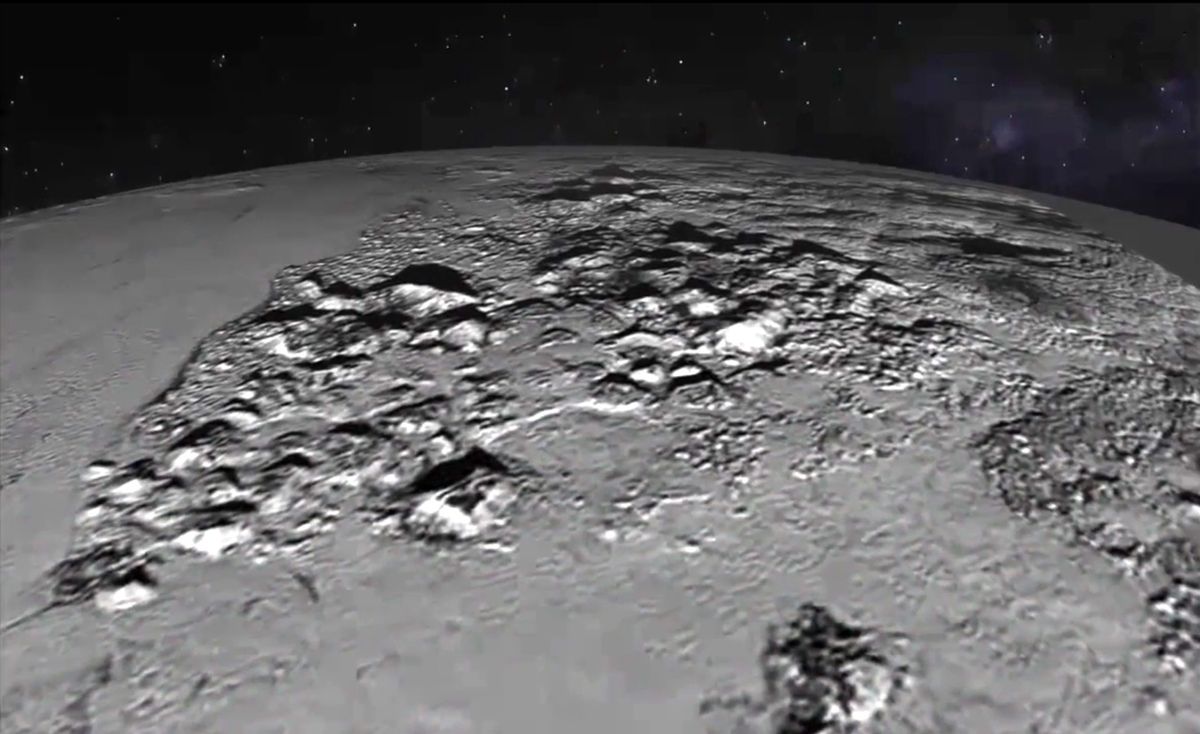

The debate has raged on the opportunity to consider Pluto as a planet since it was dubbed a dwarf planet in 2006. World views from NASA's New Horizons spacecraft in 2015 complicated things. Here, New Horizons imagined ice mountains 3 km high on Pluto during its flight over the dwarf planet in July 2015.

(Image: © NASA / JHUAPL / SWRI)

A friendly debate on Pluto's planning yesterday (29 April) ended with an informal vote in favor of restoring the status of the dwarf planet.

Early in the morning, Eastern Time, Alan Stern – the lead investigator of the New Horizons mission, flown by Pluto – followed a lively discussion of the Washington Philosophical Society earlier in the evening. tweeted that his argument won the vote, which was open to anyone who could access the PSW website, even those who were not members. The results showed that 130 people voted for the transformation of Pluto into a planet and 30 against. During the debate, Stern argued for the use of a geophysical definition define planethood. Briefly, this suggests that the planets must be bodies massive enough to adopt an almost round shape, but not enough to have nuclear fusion inside (like a star).

Related: Destination Pluto: NASA's new mission: Horizons in pictures

But since 2006, the International Astronomical Union, represented in the debate by former IAU President Ron Ekers, has used another definition of planethood, which excludes Pluto. This definition says that a planet must gravitate around the sun, must have an almost round shape and must have "cleared the neighborhood around its orbit"Historically, it is this third point that has caused the most controversy among the defenders of Pluto's planet, given the number of asteroids gravitating around the larger planets.

Pluto's global status debate intensified after the New Horizons The mission flew over the dwarf planet in 2015. New Horizons revealed a world of surprises: big mountains, a possible internal ocean and a thin "exosphere" or a very thin atmosphere. Given the complex geology of Pluto, Stern and some other members of the astronomical community began to argue that Pluto should be re-designated a planet.

On the naming of things

The debate focused on the points in detail for and against Pluto as a planet. The presentation of Ekers focused on the history of IAU, created in 1919 to coordinate clocks and issue telegram reports on discoveries relating to astronomy.

"The coordination of all the clocks that exist in the world is not a science in itself, but if we do not, it makes scientific research difficult, it's a practical function, that these unions internationals must do, "said Ekers.

In the same order of ideas, he explained, assigning categories to planets is also not a science, but a means of describing objects so that scientists can communicate. Other examples of this type of decision include agreement on names and boundaries of constellations, or description of species (such as man or homo sapiens) by their gender and a specific name.

Pluto was discovered in 1930 while we were looking for a planet that would cause irregularities in the orbit of Neptune, Ekers said. Pluto was too small to cause these disturbances, and subsequent calculations showed that the first calculations of Neptune 's orbit were incorrect. But it was still a find. The diminutive Pluto was closer to the sun at this point in its orbit than today and easier to spot in the telescopes available at that time.

It was only six decades later that other objects close to Pluto's size were discovered in the Kuiper Belt, a region of icy objects beyond Neptune. Then Mike Brown, an astronomer from the California Institute of Technology, led the discovery of an object called 2003 UB313 that would have been larger than Pluto. "No name can be assigned [by the IAU] because there was no definition of the planet, "said Ekers. (Today, we know this world by name Eris.)

IAU has twice asked the Planetary Systems Division to propose a definition of the planet; As experts are stranded, IAU has set up a nominating committee consisting of both an international representation and people working within or outside of global science (such as historians and educators ).

The committee asked that their discussions not be made public, which Ekers admitted may have been a mistake, but added that the media were invited (and present) to the decision to make Pluto a dwarf planet.

The vote took place at the August 2012 IAU meeting in Prague, which included 424 voting members (out of a total of 9,000 members). The majority vote was for Pluto to be redesignated as a dwarf planet, with a number of other "trans-Neptunian objects" discovered in the few years preceding the vote. A separate resolution, suggesting that dwarf planets should be called planets, has failed by a wide margin, he added.

"This is not a vote on science," said Ekers. "The vote at IAU is about an agreement on how you name things, and that was a big difference."

Pluto appears in color when New Horizons scientists combined four long-range reconnaissance (LORRI) spacecraft imagery images of the spacecraft with Ralph's instrument color data to create this global view in color improved. The probe obtained the images at a distance of 450,000 kilometers (280,000 miles).

(Image: © NASA / JHUAPL / SwRI)

Defend the expertise

Stern then took the stage, describing what he saw as problems with the vote of the IAU. He raised the question of the competence of the committee of the definition of the planet of IAU, saying that it should have been composed of planetary scientists: "If, God forbid, a neurological problem has been diagnosed in someone, I hope you will go to a neurologist and not a podiatrist, or some other form of doctor, because expertise is important. "

He gave a brief historical overview of three "game changers" who played a fundamental role in what he called the "dwarf planet revolution": the discovery that the oceans are common to all the "dwarf planets". other bodies of our solar system, the discovery of the Kuiper Belt of frozen objects show what the solar system looked like at the beginning of its history and the discovery of small worlds such as Pluto – most of which did not were discovered before the beginning of the 21st century.

Visitors – perhaps aboard the USS Enterprise's "Star Trek" – would look at Pluto and say that they gravitate around a planet, Stern said. "There is an atmosphere made of the same things we breathe," he said. He cited mountain ranges, glaciers, avalanches and "all the characteristics of planetary processes" visible on the surface.

Related: The dramatic journey from New Horizons to Pluto is revealed in a new book

He also interviewed Ekers on two points concerning the IAU. Stern argued that the IAU had deliberately designed the definition of planet to facilitate the memorization of the number of planets in the solar system – Ekers replied that if Stern heard that, he would probably act d & # 39; a joke at the time of the decision. Stern also said that no planet can fully clean its orbit of debris by circling the sun, while Ekers claimed that the asteroids and comets we see are resonating (in orbit together) with orbits planetary.

Stern also argued that further into the solar system, it is more difficult to eliminate small objects as they rotate much more slowly around the sun than objects closer together because of the way they work. This means that the planets must be more and more massive in the confines of the solar system to eliminate small objects. Even the Earth would not be called a planet if you moved it away from the sun between the Sun and the Earth: "It just creates confusion," Stern said.

Stern and Ekers shook hands after the debate and shared with the audience a question and answer period during which they clarified their positions. Although Pluto's status with respect to the plan has not changed as a result of the debate, be part of a larger set of studies and issues that continue – even nearly 13 years after Pluto was designated a dwarf planet.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

[ad_2]

Source link