[ad_1]

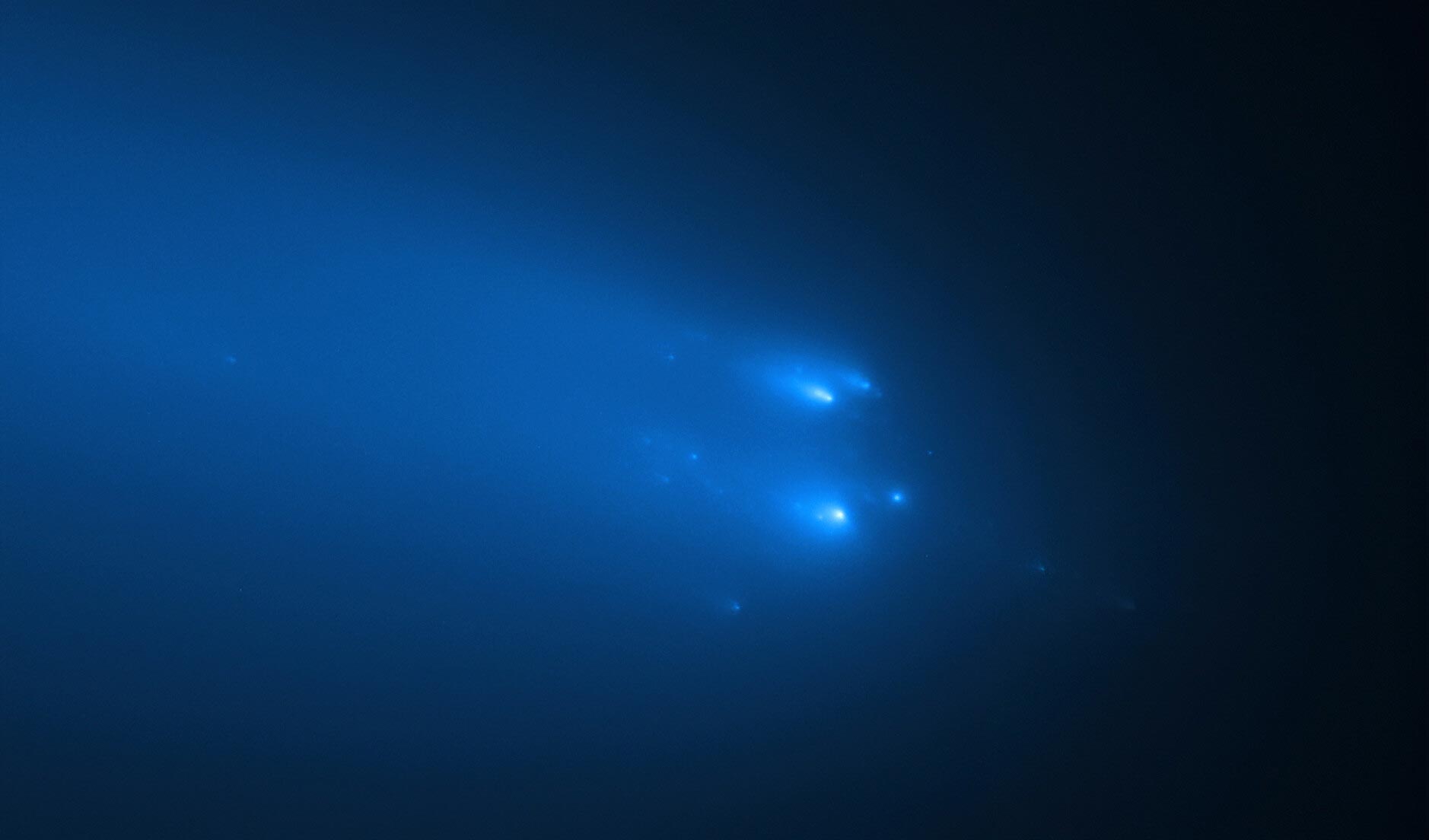

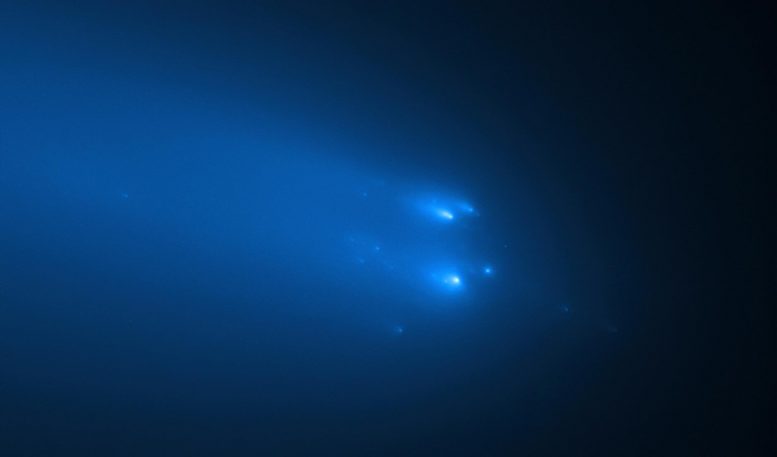

Image from the Hubble Space Telescope of Comet C / 2019 Y4 (ATLAS), taken on April 20, 2020, providing the sharpest view to date of the comet’s solid core rupture. The Hubble Eagle’s Sight identifies up to 30 distinct fragments and distinguishes rooms that are roughly the size of a house. Before the rupture, the entire nucleus of the comet could have been the length of one or two football fields. The comet was approximately 91 million miles (146 million kilometers) from Earth when the image was taken. Credit: NASA / ESA / STScI / D. Jewitt (UCLA)

A chance flyby of the tail of a disintegrated comet gave scientists a unique opportunity to study these remarkable structures, as part of new research presented today at the National Astronomy Meeting 2021.

Comet ATLAS fragmented just before its closest approach to the Sun last year, leaving its old tail trailing through space in the form of wispy clouds of dust and charged particles. The decay was observed by the Hubble Space Telescope in April 2020, but more recently the ESA Solar Orbiter spacecraft flew near the remains of the tail during its current mission.

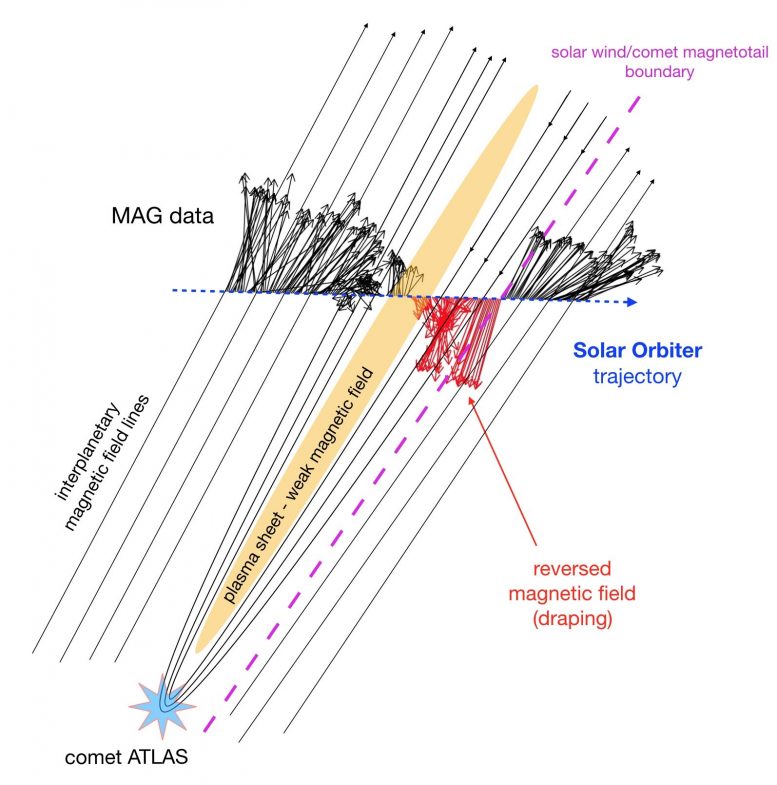

This lucky encounter offered researchers a unique opportunity to study the structure of an isolated cometary tail. Using the combined measurements from all of Solar Orbiter’s in-situ instruments, the scientists reconstructed the encounter with the ATLAS tail. The resulting model indicates that the ambient interplanetary magnetic field carried by the solar wind “rotates” around the comet and surrounds a central tail region with a weaker magnetic field.

Comets are generally characterized by two distinct tails; one is the well-known shiny, curved dust tail, the other – usually weaker – is the ion tail. The ion tail comes from the interaction between cometary gas and the surrounding solar wind, the hot gas of charged particles that constantly blows from the Sun and permeates the entire solar system.

When the solar wind interacts with a solid obstacle, such as a comet, its magnetic field is believed to bend and “drape” around it. The simultaneous presence of magnetic field draping and cometary ions released by the melting of the ice core then produces the characteristic second ion tail, which can extend great distances downstream from the comet’s nucleus.

Lorenzo Matteini, solar physicist at Imperial College London and responsible for the work, said: “This is quite a unique event and an exciting opportunity for us to study the composition and structure of comet tails in uncompromising detail. previous. Hopefully, with the Parker Solar Probe and Solar Orbiter now orbiting the Sun closer than ever, these events could become much more frequent in the future!

This is the first comet tail detection to occur so close to the Sun, well within the orbit of Venus. It is also one of the very few cases where scientists have been able to take direct measurements from a fragmented comet. The data from this encounter should contribute greatly to our understanding of the interaction of comets with the solar wind and the structure and formation of their ionic tails.

Meeting: National Astronomical Meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society

[ad_2]

Source link