[ad_1]

NASA

Nearly five years ago, NASA had to make a difficult decision. The agency had spent about $ 1.5 billion to help Boeing, SpaceX and Sierra Nevada Corporation design spacecraft that could transport US astronauts to the International Space Station. While it was looking to build flight equipment, NASA is prepared to pick only two vendors to go forward – both to generate healthy competition and to provide access redundant in space.

NASA had a total of $ 7 billion to distribute to winning companies to finalize the development of their spacecraft, integrate their rockets, and perform each up to six missions after NASA certified these vehicles worthy of winning. the place.

Publicly, some Boeing officials denounced SpaceX, highlighting their own legacy of blue blood. Boeing has since 1961 had a successful working relationship with NASA and is the first stage of the Saturn V. Boeing rocket would note instead that Elon Musk seemed more interested in flashy marketing and had never achieved his goals. launch. "We are looking for substance," said John Elbon, head of Boeing's space division. "Not hot."

Behind the scenes, Boeing was pushing hard to win all NASA's commercial crew program funding, and the company encouraged NASA to opt for the safe choice of SpaceX and Sierra Nevada space flight newcomers. "We fought to keep two suppliers, as well as members of Congress, lobbyists, and some NASA members struggling to select the lowest Boeing," a government source told Ars.

In the end, NASA's chief of manned space flight, William Gerstenmaier, selected two suppliers, Boeing and SpaceX. This decision proved wise for reasons of cost and schedule. NASA's director, Jim Bridenstine, is considering new approaches to bring humans back to the moon with a reasonable budget and schedule.

Cost disparity

In terms of costs, NASA gets a better deal from SpaceX. The best way to determine costs may be the "headquarters price", the amount NASA pays to bring one of its astronauts to the International Space Station. In recent years, since the withdrawal of the space shuttle in 2011, NASA has paid Russia up to 81.8 million dollars per seat.

NASA has rarely spoken of the "seat price" for commercial crews. In fact, it was mentioned only during Congressional hearings, when Gerstenmaier announced a figure of 58 million dollars. "Assuming that the 12 missions are bought and flown at a rate of two per year, the average price of a seat is $ 58 million per seat for commercial crews," he said in 2015. .

NASA

However, this number does not reflect what NASA pays Boeing and SpaceX individually. According to the United States Government Accountability Office, the agreement on commercial teams includes three main lines of funding: line item 001 is for development and testing, line item 002 is for service missions, and line item 003 is for special tests, studies and analyzes. To determine the price per seat, we need to know the value of line item 002 and then divide by the number of seats per flight (four) and per flight (up to six).

Neither the agency nor the companies have publicly disclosed the values for line item 001 or line item 002. But we can make a very good estimate. By subtracting line item 003 (up to $ 150 million per company), knowing the total value of the contracts and using the average value of $ 58 million awarded to NASA, we can go back to the total value of line item 002$ 2.784 billion. This is the total amount that NASA paid for 12 operational flights to the space station from 2020 to 2024, for a total of 48 seats of both companies.

Turning now to the last step, NASA awarded Boeing $ 4.2 billion for its commercial crew contract and $ 2.6 billion for SpaceX. If this proportion of funding is valid for line item 002According to a NASA source more or less accurate, the price of seats that NASA pays Boeing and SpaceX is significantly different. According to this analysis, NASA will pay Boeing approximately $ 71.6 million per Starliner seat and $ 44.4 million per SpaceX per Dragon seat.

Why is NASA paying so much more to Boeing? Probably because the company asked for it. As part of this competition, SpaceX has bet on a low price, believing that the space agency would give priority to lower prices. "Knowing that I could have bid more after the fact, I hope to have more," said Gwynne Shotwell, President of SpaceX, about this price gap in 2018. Essentially, competition has grown SpaceX to offer a lower price.

Program

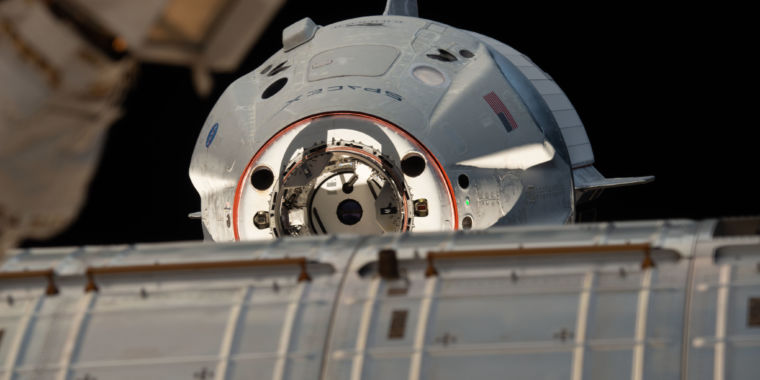

Although NASA receives less money and has less space flight experience, it now seems likely that SpaceX will offer crew capability more quickly. The California company has already completed its demonstration mission for NASA a month ago and is currently working on the final tests that will allow it to conduct its first crewed mission later this year, probably not until October.

On the other hand, Boeing will not perform its first unprepared demonstration mission until at least August, and NASA has acknowledged that this date may well fall back again. A disturbing sign for Boeing is that the company still has not conducted a launch pad abandonment test – during which Starliner's emergency exhaust system is triggered from the launch pad to ensure that the capsule can move away quickly from the rocket if there is a launch problem.

This test was originally scheduled for June 2018, but it was delayed indefinitely as a result of an anomaly that occurred this month during a high-fire test of the engines that interrupted the launch. After this accident, which Boeing did not publicly disclose until a report to Ars nearly a month later, the company states: "We are confident that we have found the cause and we take corrective action. " However, 10 months after the incident, Boeing is only "getting ready to revive" a campaign that will result in a dropping test in the future.

SpaceX has had its own technical challenges with the Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon parachutes, but it now seems likely to provide a finished product to NASA before Boeing for several months, for less money. It seems likely that SpaceX will send its crew into space before Boeing launches a Starliner demonstration mission. If NASA had placed a sole-source contract with Boeing for a commercial crew, not only would the agency have had a single supplier with a higher price, it would probably have had to wait longer for this product.

The implication here for NASA, as it seeks to extend the human space flight from low Earth orbit to deep space, seems clear. If the agency is serious about lunar landings by 2024, it has a lot of contracts to define soon: Gateway modules, lunar landing gear components, space suits and rockets allowing the Set of this material to be put into lunar orbit. The lesson to be learned from the commercial teams is that healthy competition between suppliers is good, that commercial contracts can drive down prices, and that having a long-standing successful business in space flying does not necessarily mean that performance will be better than that of new children. block.

[ad_2]

Source link