[ad_1]

In a rare sign of material progress, SpaceX and the FAA have finally released what is called a draft environmental assessment (EA) of the company’s South Texas Starship launch plans.

Planned to be the largest and most powerful rocket in spaceflight history on its first orbital launches, the process of obtaining clearance to launch Starship and its Super Heavy booster out of the coastal wetlands South Texas was never going to be easy. The Boca Chica site where SpaceX eventually settled for its first private launch facilities – initially intended for Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy but later dedicated to BFR (now Starship) – is simultaneously surrounded by sensitive coastal habitats populated by several threatened or endangered species located only miles as the crow flies from a city with a temporary population ranging from a few thousand to several tens of thousands.

Reception and analysis of the project and its schedule have been mixed. On the one hand, SpaceX’s EA project – completed with oversight from the FAA and help from the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) – gives a number of reasons for optimism. As a sign that SpaceX is taking a pragmatic approach to the inevitable hurdles to environmental review and launch license approval ahead of the South Texas Starship’s orbital launches, the company has in fact pursued what is known as an “environmental assessment.” programmatic ”(PEA).

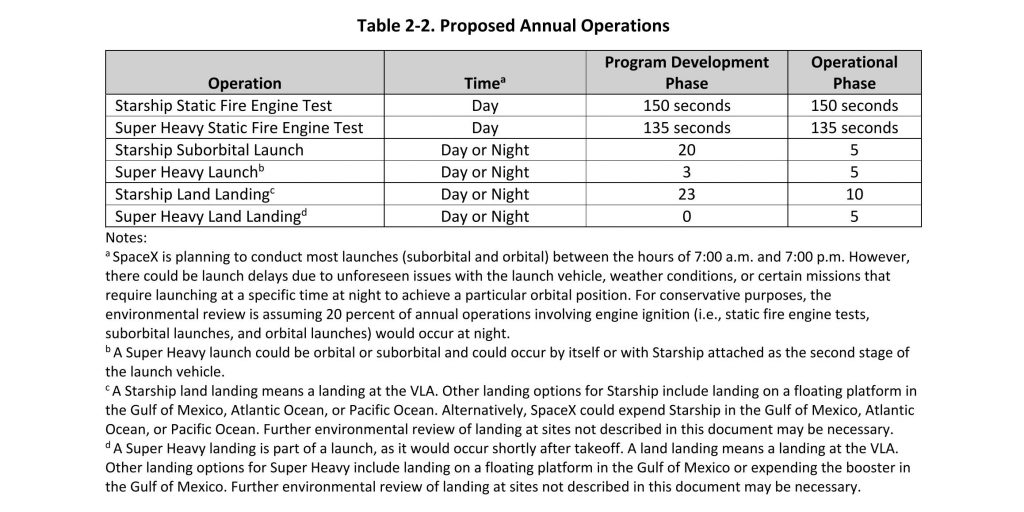

More importantly, this means that SpaceX’s Starbase PEA – if approved – will look more like a foundation or stepping stone that should make it easier to start small and methodically expand the scope and nature of the company’s plans for Boca. Chica. In this sense, as part of Starbase’s first dedicated EA, SpaceX has proposed a maximum of 23 flight operations per year while Starship is still in development, including up to 20 suborbital test flights of Starship and 3 orbital launches (or super heavy hops). Once SpaceX determines enough issues for slightly more confident Starship operations, the company would enter an “operational phase” that would allow up to five suborbital Starship launches and five orbital Starship launches, as well as ship landings. and boosters on earth. after the 10 possible launches.

In other words, SpaceX’s initial PEA project is extremely Conservative, seeking permission for what amounts to a bare minimum concept of operations for Starship’s orbital launches. With a maximum of 3 to 5 orbital launches per year, a PEA and subsequent launch license approved as is would likely give SpaceX just enough headroom to perform basic Earth orbit launches and no more than one or two test runs. orbital filling per year. However, as an example, a maximum of five launches would almost entirely prevent SpaceX from launching Starship to Mars, the Moon, and perhaps even high-energy Earth orbits without using all of its annual launch allowances on a single mission.

Perhaps more importantly, the draft PEA as proposed would unequivocally prevent SpaceX from performing the lunar landings of the NASA Human Landing System (HLS) for which it was awarded a nearly $ 3 billion contract. . Each HLS Starship Moon landing is expected to require between 10 and 16 launches to deliver a depot ship, an HLS lander, and approximately 1,200 tonnes of propellant into orbit. However, when it comes to SpaceX’s prospects of developing Starship as quickly as possible, that’s actually a good thing. First and foremost, SpaceX’s lean PEA project should be far easier to approve by the FAA than a PEA seeking ultimate Starship clearance ambitions – tens to hundreds of launches each year – since the beginning. In theory, with this approved barebone PEA, SpaceX would then be able to build based on additional EAs – like, for example, extending Starship’s maximum launch rate.

Of course, SpaceX first needs the FAA to turn that first draft PEA into a favorable EA (not a guarantee) before any of the above start to matter. Based on the content of the project itself and the associated appendices, SpaceX appears to have a decent chance of receiving a “No Significant Impact Finding (FONSI)” or “FONSI Mitigation” determination. However, SpaceX began the process of creating this project as early as mid-2020, followed by an FAA announcement in November 2020. The implication is that the FAA managed to drag out a project release process that, some say should have taken 3-4 months in a tough 10-15 month ordeal.

Combined with the uphill battle it starts to look like SpaceX will have to fight for a Starship orbital launch license in South Texas, it is increasingly likely that Starship, Super Heavy, and Starbase will be technically ready for testing. orbital launch long before the FAA was ready to approve or authorize them. Barring delay, the public now has until mid-October to read and comment on SpaceX’s draft PEA, after which the FAA and SpaceX will review those comments and hopefully turn the draft into a completed review. Even if the FAA sort of only took two months to fire a FONSI in the best-case scenario, clearing the starbase of environmental hurdles to launch, it’s hard to imagine the agency could then turn around and approve. a spacecraft orbital launch license – or even just one. outside experimental permit – in the last weeks of 2021.

Ultimately, that means that nothing less than a minor miracle is likely to prevent the environmental review and FAA licensing delays from directly delaying the debut of Starship’s orbital launch. There’s at least a chance that the Starship, Super Heavy, and Starbase orbital launch site won’t be ready for orbital launches by the end of the year, but it’s increasingly hard to imagine that the three will not be tested, qualified and ready for action in a month or two from now. For now, we’ll just have to wait and see where the cards fall.

[ad_2]

Source link