[ad_1]

Like a bowl of spaghetti noodles overturned on the bottom of the North Sea, a vast array of hidden tunnel valleys meander and meander through what was once an ice-covered landscape.

These valleys are remnants of ancient rivers that once drained water from melting ice caps.

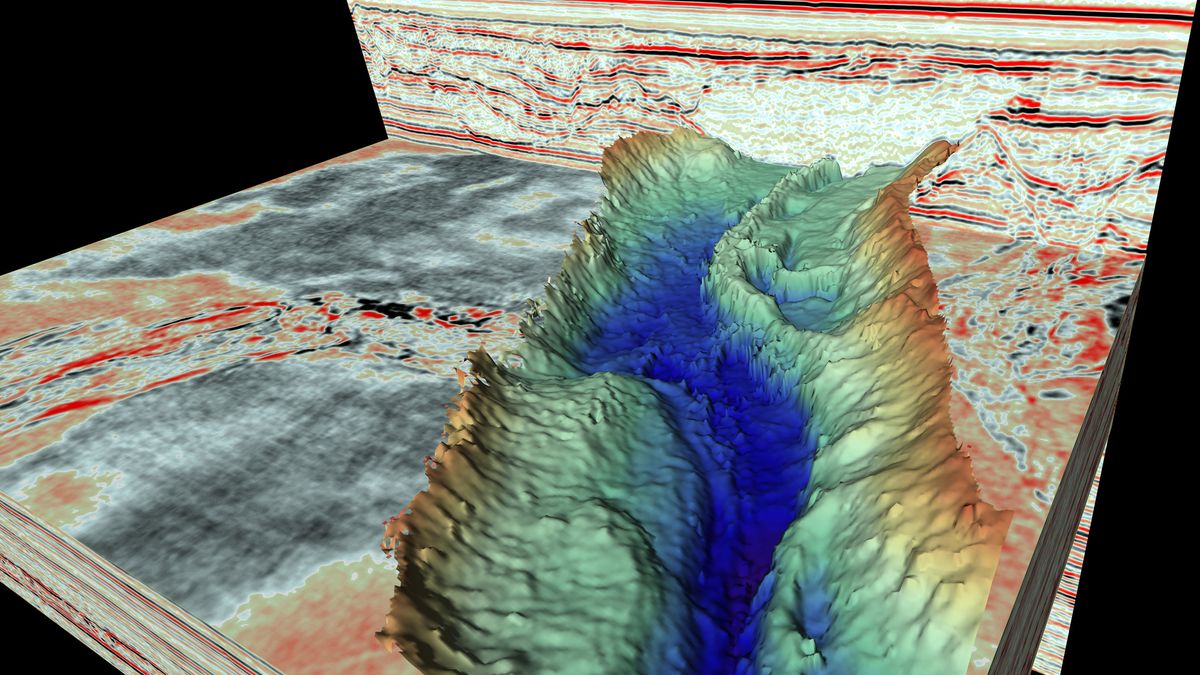

Now scientists have got the clearest view of these channels to date. They are buried hundreds of feet below the seabed, and they are huge, ranging from about 0.6 to 3.7 miles (1 to 6 kilometers) wide.

The new imagery reveals fine detail within these vast features: small, delicate ridges of sediment, larger walls of sediment up to miles long, and craters called kettleholes left by melting chunks of ice.

Related: See photos of the disappearance of the Earth’s ice

“We didn’t expect to find these kinds of ice cap imprints in the channels themselves,” said lead author of the study, James Kirkham, a marine geophysicist with the British Antarctic Survey and the University. from Cambridge. “And that tells us, in fact, that the ice interacted with the channels a lot more than previously assumed.”

These canals are the footprints of glaciers left between 700,000 and 100,000 years ago, when most of the North Sea, as well as the northern two-thirds of the UK and all of Ireland were often buried under huge ice caps. (The ice has moved forward and backward seven or eight times during this period, Kirkham told Live Science.)

During times when the climate warmed and the ice was retreating, these ice caps dumped water through glacial channels hidden under the ice. These canals have left their mark on the sediments below. Other sediment then piled up as the ice disappeared, burying the footprints deep under the seabed.

To view these ancient impressions, geophysicists use a technology called 3D reflection seismic. In this process, scientists project gusts of compressed air towards the seabed. The resulting sound waves pass through layers of rock and sediment beneath the seabed and bounce back, where they are picked up by a receiver on board the ship. Since sound travels at different speeds through different types of rocks and sediments, the data can be reconstructed into an image of the subsoil.

A map of the underwater tunnel valleys looks like a vast array of scribbles, like a scattering of upturned noodles. But when zoomed in, the channels are visible in stunning detail. They meander and snake like rivers (which they once were), bounded by sheer cliffs and rugged slopes. Some dive 310 miles (500 km) deep in the sediment and are tens of miles long.

Water and ice

The landforms in the tunnel valleys paint a complicated picture of the ice retreat, Kirkham said. Sometimes there are signs of fairly slow and steady recoil. For example, eskers are ridges of sediment about 5 meters high that can extend for several kilometers. They are also seen in modern glaciers that move gradually.

Related: Photos: Ancient human remains found under the North Sea

In other places, the channels are punctuated with small, delicate ridges that indicate rapid and dynamic ice flow, Kirkham said. Another sign of rapid ice and water surges are kettle holes, which are places where a large iceberg that has broken away from the main ice cap and has moved to a new location gets stuck and melts.

The canals appear to have been carved out by both water and ice. In some places, braided canals meander through the bottom of the canyons, Kirkham said. These were formed by the flow of water, which appears to have eroded the sediment beneath the ice cap. Once that void formed, however, the underside of the ice sagged into this space, carving a wider path. There are also places where the valley walls appear to have collapsed, likely after the ice that filled the valley had melted, allowing sediment to sag in its place.

These underwater tunnel valleys are an interesting snapshot of the past, but their real value may be in helping predict the future. As the climate warms, the ice caps are retreating again. If the climate gets hot enough, Western antarctica could one day look a lot like the North Sea 100,000 years ago, Kirkham said. The Greenland ice cap too, melts quickly. Studying the remains of the North Sea channels and their formation may reveal more about the dynamics governing the loss of current ice caps. In particular, geological records could indicate how small-scale factors like moving water affect how much ice eventually melts in the sea, and how fast, which could lead to better models of sea level rise. sea level.

“In the future, we would like to explore this idea a bit more by continuing to map, as well as perform computer modeling to determine how we produced these landforms and what should happen at the base of an ice cap. glacial to generate them, ”Kirkham said.

The results appear today (September 8) in the journal Geology.

Originally posted on Live Science

[ad_2]

Source link