[ad_1]

A Stanford scientist has developed what could be the first simple blood test for chronic fatigue syndrome, a confusing and often debilitating disease that can take years to diagnose and is still largely misunderstood by traditional medicine.

The diagnostic test is based on Stanford Biochemist Ron Davis' discovery of a biological marker that distinguishes people with chronic fatigue syndrome from those who are healthy. A description of the biomarker and how it could be used was published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Assuming its results are verified, the biomarker would be a breakthrough in disease research. This could facilitate the diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome and help scientists develop treatments for this condition. And perhaps just as important, the biomarker provides additional validation for a disease that has long been dismissed or even described as imaginary.

"There are doctors around who say that there is no biomarker, the disease does not exist, as far as it's concerned," Davis said. "So there was a real effort to find a biomarker. I hope this will help the medical community to accept the fact that it is a real illness. "

The original Davis study was small and involved only 40 people. He will then have to reproduce his results in much larger trials before he can widely disseminate the blood test. Patients and scientists in the field expressed enthusiasm for the work they have done so far.

"It's a major step. If this holds up in greater numbers, it could be a transformative step forward, "said Robert Naviaux, a professor of genetics at UC San Diego, who knows Stanford's work but did not participate in biomarker research.

Chronic fatigue syndrome is thought to affect several million people in the United States, although some reports suggest that 90% of people with it have not been diagnosed. The disease can cause great fatigue, to the point that many people spend years without being able to leave their beds and many others are unable to work or have a normal social life.

In addition to fatigue, symptoms may include chronic pain, memory and concentration problems, gastrointestinal problems, and extreme sensitivity to light, sound, and smell. Several organ systems can be assigned at a time. One of the most common effects is post-exercise discomfort, in which people suffer from a severe worsening of symptoms after physical activity.

The disease is officially called myalgic encephalomyelitis / chronic fatigue syndrome (ME / CFS); the first half is a reference to muscle pain associated with inflammation of the nervous system. Although the name chronic fatigue syndrome is most often associated with the disease, many patients, doctors and scientists avoid it because they say it alleviates the debilitating nature of the symptoms.

There is no medical treatment for chronic fatigue syndrome. Indeed, Davis hopes that his diagnostic test could help scientists to look for drugs that can ease the symptoms or cure the disease. It would also be easier for physicians to identify participants in clinical trials, which could speed up research on the cause of the disease and the best ways to treat it.

But the biggest benefit of a diagnostic tool would be for patients, many of whom endure years of frustration and misdiagnosis before discovering what's wrong with them. Davis' findings would allow doctors and other providers to diagnose patients in a matter of hours on the basis of a blood test, instead of sifting through a subjective range of symptoms.

Jaime Seltzer, who works with the ME Action Patient Advocacy Group, was diagnosed with the syndrome fairly quickly about five years ago because she knew other people with the disease and that she recognized the symptoms. symptoms. But she said that many people wait not only years before getting a diagnosis, but are told in the meantime that their symptoms are in their head or that they can improve with it. # 39; exercise.

"And it's literally the worst advice you can give to anyone with ME," said Seltzer, since post-exercise discomfort is such a common symptom of the disease.

"It's absolutely breathtaking," she said. "But a biomarker can and will change that."

Chronic fatigue syndrome is currently diagnosed through a symptom checklist. The diagnosis is not difficult, said Maureen Hanson, a professor of molecular biology and genetics at Cornell University, who helped develop the list. But many primary care physicians do not know the symptoms or are not yet convinced of the reality of the syndrome.

"Most people with this disease consult four or five doctors before the diagnosis," Hanson said. "If there was a simple blood test to discover, to provide objective data rather than a list of symptoms, it would be helpful to obtain an accurate diagnosis."

The biomarker discovered by Davis is based on the reaction of immune cells to stress. In his studies, Davis collected the participants' blood and then filtered it into a sample containing only immune cells and plasma. He exposed the salt sample, which is stressful for the cells, forcing them to use energy to maintain an appropriate sodium balance.

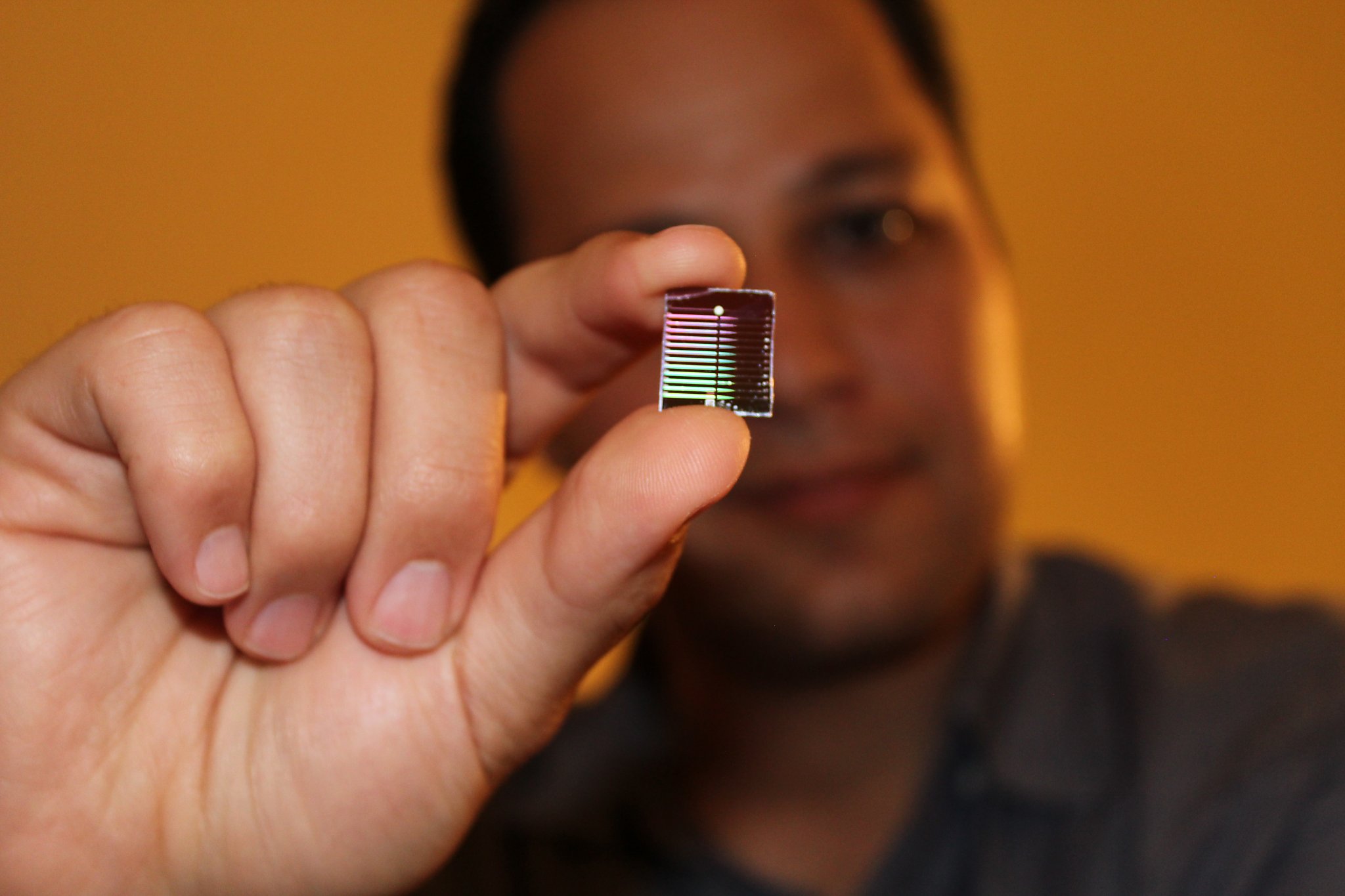

The stressed sample was then passed through a microchip the size of a postage stamp, which used an electric current to indirectly measure the energy stress. Less effort means that cells have little trouble maintaining sodium balance, and more stress means they struggle.

Davis found that the test correctly associated a high energy expenditure to the 20 participants already suffering from chronic fatigue syndrome. Blood samples taken from 20 healthy people showed a significantly reduced energy effort.

His research, which costs about $ 200,000, was funded almost entirely by a patient advocacy foundation. And Davis himself is a patient advocate: his son has had chronic fatigue syndrome for almost 10 years and has been bedridden for most of the time.

"He is 35. He has already lost a good part of his life," said Davis. "The good news is that it does not worsen. But I fear he will come down and I will not find out before he dies. "

As enthusiastic as he may have found a biological marker of the disease, "we still need to know exactly what causes it," Davis said. "Then you can know how to treat it. You can fix it.

Erin Allday is a writer at the San Francisco Chronicle. Email: [email protected] Twitter: @erinallday

[ad_2]

Source link