[ad_1]

One day, humans will pull themselves together and dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But – so as not to check your daydreams too strictly here – how exactly are global temperatures going to react on this day? This is a question that climate science has long sought to answer, although the devils in the details have led to some confusion.

A new study conducted by Chen Zhou of Nanjing University tracks down another devil and exposes him. Research has increasingly shown that it is not only the average temperature of the planet’s surface that matters in tracking warming, but also the spatial pattern of these temperatures. This may be important for calculating things like the sensitivity of the climate to greenhouse gases, but it has not been taken into account in some methods of estimating the impact of emission reductions on warming.

See a model

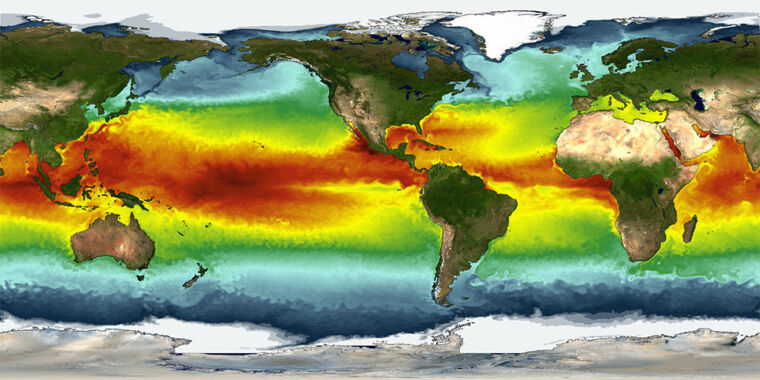

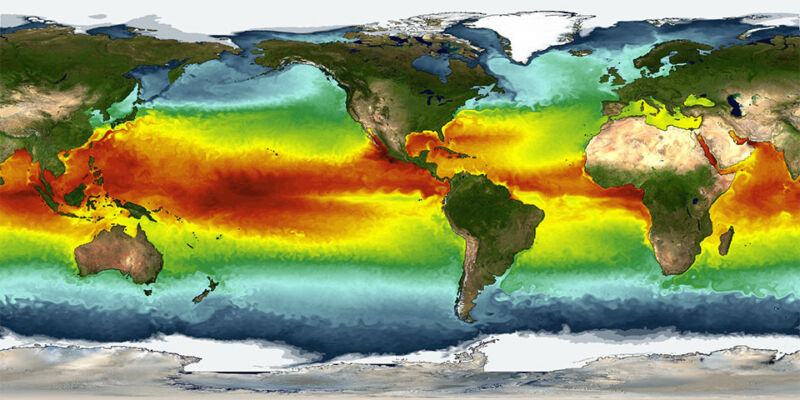

This “pattern effect” of warming in different regions of the globe influences the way the planet rejects heat back into space. For example, if the warming is a bit stronger in the Western Equatorial Pacific Ocean – which it has been – this region is more apt to produce cloud cover reflecting sunlight and releasing heat upward. . If you assume that warming is happening evenly around the world, you will miss this slightly compensating behavior.

Building on previous work, the researchers calculated the influence of the model effect on the world today by comparing historical observations to climate model simulations of a pre-industrial revolution climate. They then tested the numbers of model effects using satellite measurements of the Earth’s overall energy balance over the past decades. In the absence of a model effect, the estimated accumulation of energy in Earth’s climate is somewhat higher than satellite measurements. But the mixture of their numbers of model effects gives predictions that match the measures well, including oscillations from year to year.

What does this mean for a low emissions future? One way to calculate this was to use the enhancement of the man-made greenhouse effect and the past temperature change. Based on this calculation of Earth’s climate sensitivity, you could then ask how much warming is expected to occur once greenhouse gases stop increasing. Because the climate (mainly the oceans) cannot instantly equilibrate to a stronger greenhouse effect, temperatures take some time to fully catch up.

But where will he be once he catches up? If the model effect dampened Earth’s past response, there could be more warming in the pipeline and a warmer end result.

Fear of commitment

The calculations of warming we’ve already committed to also critically depend on assumptions about what our future emissions will look like – a major source of confusion. The scenario used in this article is one where we reduce emissions enough to simply maintain current concentrations of greenhouse gases. They don’t go up any more, but they don’t go down either. In this simple scenario, the climate system has the opportunity to catch up and achieve a new equilibrium. However, it is not a zero Emissions scenario, in which we stop all emissions and the concentrations of greenhouse gases slowly begin to decrease as the Earth absorbs them.

With this in mind, the results show that taking into account the model effect should increase the warming initiated. For concentrations stabilizing at 2020 levels, if we wait centuries for temperatures to equilibrate, the total warming since pre-industrial times goes from about 1.3 ° C to 2.3 ° C. (We have until ‘now experienced a warming of about 1.1 ° C.)

Another version of this scenario allows gases and short-lived particles to disappear; here, the ultimate warming goes from 1.6 ° C to 2.8 ° C. By limiting this very long-term view to only the year 2100, the warming goes from 1.3 ° C to 1.8 ° C in taking into account the model effect.

The exact numbers aren’t really the point here – the researchers note that using a different data set for past ocean temperatures decreases the differences. It is the general finding – the existence of the model effect implies a more committed warming – which is potentially important. This could mean that if you really want to permanently limit warming to a certain target, like 1.5 ° C or 2 ° C, you have to err on the side of even lower emissions (or plan to actively remove more CO2 later).

But that shouldn’t trigger fears that global warming is suddenly inevitable. A future of constant concentration is different from a future with zero emissions, and final temperatures only arrive after long enough horizons. The real contribution of the study is to fill a gap in certain methods of calculating our committed warming. And we need to show our commitment to stop warming first if we want any of those scenarios – or better scenarios – to become a future we can choose from.

Nature Climate Change, 2020. DOI: 10.1038 / s41558-020-00955-x (About DOIs).

[ad_2]

Source link