[ad_1]

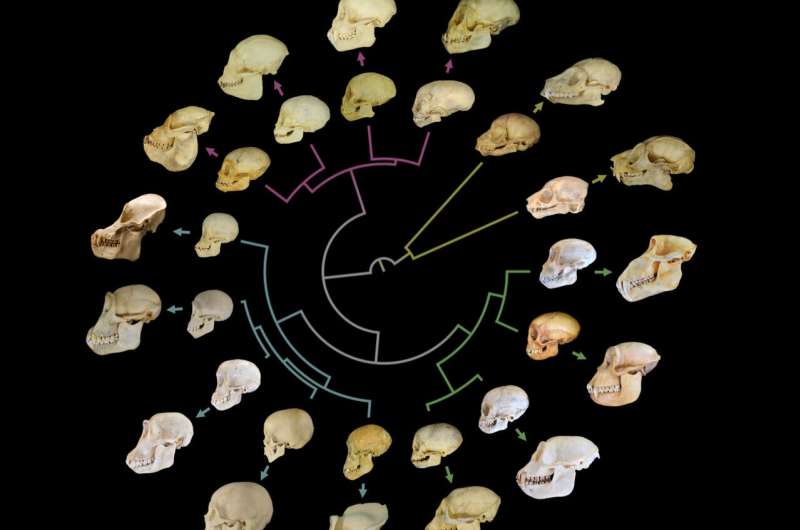

Circular evolutionary tree showing skull growth and associated changes in the chewing apparatus in juvenile (inner ring) and adult (outer ring) primate skulls. The study includes species of monkeys and humans (blue arrows), Central and South American monkeys (pink arrows), Asian and African monkeys (green arrows), and lemurs and lorises (yellow arrows). . Credit: H. Glowacka and GT Schwartz

Six, 12 and 18 years old. These are the ages at which most people have their adult third molars or large chewing teeth towards the back of the mouth. These teeth come at a much older age than our closest living relative, the chimpanzee, who gets those same adult molars around the age of three, six and 12. Paleoanthropologists have long wondered how and why humans developed molars that emerge in the mouth at these specific ages, and why these ages are so late compared to living apes. Scientists at the University of Arizona and Arizona State University unveil study on Scientists progress this week they think they’ve finally solved the case.

Humans are unusual primates. We are very intelligent learners, extremely social, remarkably resourceful, capable, qualified teachers and, therefore, remarkably successful evolutionary. A key aspect of our biology enabling these components of human experience to evolve is our unique ‘life story’, or the overall pace of life, including how fast we grow, how long we depend on mothers for nutritional support, how long it takes us to reach sexual maturity, and how long we live. Surprisingly, the clues to most of these components of our human biology are linked to our teeth.

The only dental characteristic intimately associated with the rate of growth and the history of life is the age at which our adult molars cut the gum tissue. For many decades, evolutionary anthropologists have taken advantage of the very close relationship – which exists in all primates – between the rate at which these adult molars emerge in the mouth and the general rate of life. Modern humans, for example, grow incredibly slowly, have a very long and prolonged life history, and emerge their adult molars very late in life, later than any other living or extinct primate.

“One of the mysteries of human biological development is how the precise synchronization between molar emergence and the history of life occurred and how it is regulated,” said Halszka Glowacka, lead author and assistant professor. at the University of Arizona, College of Medicine-Phoenix.

Glowacka and paleoanthropologist Gary Schwartz, a researcher at the Institute of Human Origins and professor at the School of Human Evolution and Social Change, published their study this week which provides the first clear answer: it is the coordination between facial growth and the mechanics of chewing muscles which not only determines or corn when adult molars emerge. This delicate dance results in the entry of the molars only when a “mechanically safe” space is created. Molars that emerge “ahead of schedule” would do so in a space that, when chewed, would disrupt the precise functioning of the entire chewing apparatus by damaging the jaw joint.

For the study, Glowacka and Schwartz created 3D biomechanical models of skulls, including the attachment positions of each major masticator muscle, throughout the growth period in nearly two dozen different species of primates ranging from small lemurs with gorillas. When combined with details of the jawbone growth rates in these species, their integrative models revealed the precise spatial relationship and temporal synchrony of each emerging molar against the backdrop of the growing and changing masticatory system.

The authors note that this research establishes two things: It convincingly demonstrates that it is the precise biomechanical relationship between growing faces and growing masticatory muscles that drives the close and predictive relationship between dental development and the history of tooth development. life, and it reveals that our species’ delayed molar emergence programs are the result of the evolution of slow overall growth associated with short jaws and retracted faces, faces located directly below our brains.

Their study found that the combination of jaw growth rate and jaw length or protrusion in adults determines when molars will emerge. Modern humans are special among primates given our extended growth profiles and retracted faces with short dental arches.

“It turns out that our jaws grow very slowly, possibly due to our overall slow life histories and, in combination with our short faces, delays when a mechanically safe space – or a ‘sweet spot’ if you will – is available, resulting in our very late ages at the emergence of molars, ”said Schwartz.

“This study provides a powerful new lens through which the long-known links between tooth development, skull growth and maturation patterns can be visualized,” said Glowacka.

The researchers plan to apply their model to fossil human skulls to answer questions about when slowed jaw growth and delayed molar emergence first appeared in our fossil ancestors.

They also realize that the approach taken in this study could have implications for clinical dentistry. Because molars only emerge when sufficient facial growth has occurred and the sweet spot appears, “the finer details of the model could be explored in more samples to help understand the phenomenon. impacted wisdom teeth in humans, ”noted Glowacka.

Researchers reconstruct precise bite from early mammal

A biomechanical perspective on molar emergence and the life cycle of primates, Scientists progress (2021). DOI: 10.1126 / sciadv.abj0335

Provided by Arizona State University

Quote: Study of skull growth and tooth emergence reveals timing is everything (2021, October 6) retrieved October 6, 2021 from https://phys.org/news/2021-10-skull -growth-tooth-emergence-reveals.html

This document is subject to copyright. Other than fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.

[ad_2]

Source link