[ad_1]

Sign up here for our daily coronavirus newsletter on what you need to know, and Subscribe to our Covid-19 podcast for the latest news and analysis.

In Mississippi, an online vaccine registration system has buckled in a sudden surge in traffic. Officials at a local health department in Georgia had to count every dose they received before making appointments. A $ 44 million national vaccine planning and monitoring system goes largely unused by states.

And California, Idaho and North Dakota undercounted vaccinations because workers forgot to click a “submit” button at the end of the day.

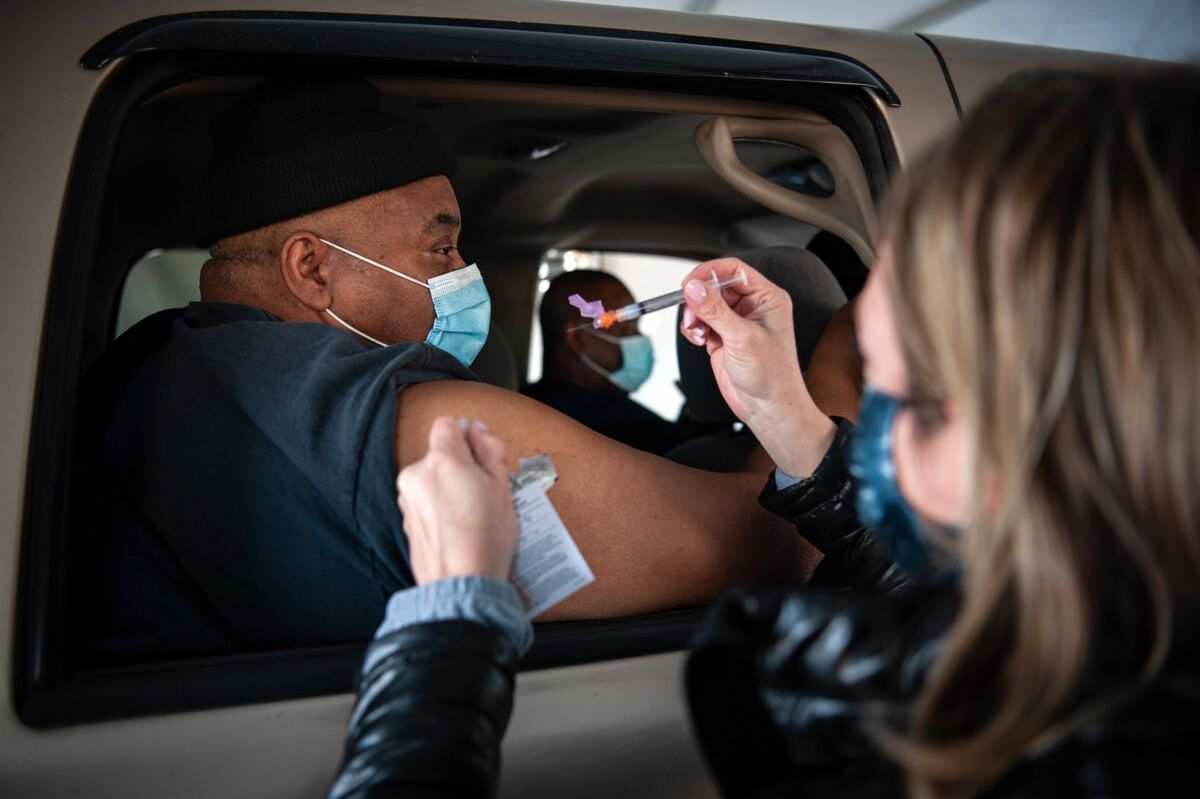

Across the United States, a vaccination campaign meant to turn the tide of the pandemic and boost the country’s economic recovery is mired in technical glitches and software glitches. Cash-strapped public health departments are trying to keep their websites from crumbling while scheduling millions of appointments, tracking an unpredictable inventory and recording how many hits they give.

The situation in the United States, home to tech giants, is frustrating a public hungry for vaccinations. In addition, data gaps could skew the national picture of the effectiveness of vaccine use if a number of administered doses are not counted.

“Our feeling is that this is a substantial amount,” said Marcus Plescia, chief medical officer of the Association of State and Territory Health Officials. “It will become clearer as data systems improve and we get a better idea of what we are missing.”

Fill gaps

This is a situation that some officials saw coming. Former Center for Disease Control and Prevention director Robert Redfield cited “years of underinvestment” in public health systems in his testimony to Congress in September. He went on to say that the Trump administration planned to help states fill gaps in IT capacity.

“I hope there will be additional resources to start filling these gaps, as it will be very important that we have reports for the surveillance and safety of these vaccines,” he said.

Redfield and groups representing public health officials told lawmakers billions of investments would be needed to help states distribute photos. But Congress didn’t allocate that money until it passed a fundraising bill in late December, after states had already started vaccinating people.

Private companies that administer vaccines have their own problems. Jarred Phillips, his sister, mother and father took turns looking on the website of Walgreens Boots Alliance Inc. to find a vaccination appointment for her mom. The process included creating an account, searching by zip code, then by store, by day, and by three hour time slot.

Nothing came. Phillips, a 36-year-old technician from Wilmington, Delaware, even looked for rural zip codes where demand might be low. Nothing. Hours later, he couldn’t understand why the process was so complicated.

“At some point, these solutions have to meet people where they are,” he said.

Walgreens spokeswoman Kelli Teno said the company has “dedicated teams actively working on these issues to ensure an easy, secure and transparent experience for all eligible people” trying to schedule their vaccinations.

Patchwork systems

Like much of the US response to the coronavirus pandemic, the vaccination effort has been deployed in a patchwork approach. And it has been superimposed on an already fragmented healthcare system. The result is a mishmash of digital systems across the country that has exasperated many who attempt to use them.

“The biggest mistake was that the government was a bit too focused on the first problem: how to get vaccines and ship them to different places,” said Eren Bali, co-founder and CEO of Carbon Health Technologies Inc. “It was definitely an oversight that didn’t start sooner.”

So far, approximately 49 million doses have been distributed across the United States. About 23.5 million people received their first of two injections and 5 million received both, according to Bloomberg Vaccine monitoring. Last month, Trump administration officials predicted that 30 million people could be fully vaccinated by the end of January.

Registration of people in advance is encouraged to avoid crowds in clinics, especially with the virus continuing to rise in many communities. But registrations have been chaotic at times, especially for the elderly who are among the first in line for vaccines, with the websites for dating lottery-like dates.

Before opening appointments, Gwinnett, Newton, and Rockdale County Health Departments in Georgia first count her inventory. The expected supply may change weekly and the amount that actually arrives may differ. The Department of Health relies on Bookly, a web plug-in it started using last year for coronavirus testing.

New appointments open once a week. They are filled in hours.

“It’s difficult to communicate with the public to know when nominations are open,” said Audrey Arona, director. “I know there is a lot of frustration in constantly having to sit on the website for dates opening.”

The Georgia Department of Public Health is working on a centralized planning system. The tool is expected to be ready by mid-February, spokeswoman Nancy Nydam said in an email.

In Florida, several counties turned to the Eventbrite ticketing website when the state expanded eligibility to people 65 and older. Los Angeles scrapped a software called PrepMod because it couldn’t handle the rush to record. Instead, the city turned to Carbon Health, which operates a chain of health clinics. The company set up an online tool for finding testing sites, and it built a vaccine platform from there.

Vaccination monitoring

Christus Health staff spent as much time documenting and reporting vaccinations as they did administering vaccines, said Sam Bagchi, clinical director of the health system based in Irving, Texas. Christus has administered approximately 65,000 doses in Texas, Louisiana and New Mexico.

Injections are reported to states differently depending on who receives them: one electronic health record for employees, one for their patients, and, until recently, paper forms for people who were neither patients nor members of the hospital. staff.

Christus separately counts its vaccine inventory manually and types the data into a web form for the State. Existing systems are not “meant to track minute by minute, hour by hour, day after day, what’s given and what’s not,” Bagchi said.

Public health technology systems are not designed for the precision necessary for the mass vaccination effort, said Joseph Kanter, an official with the Louisiana Department of Health.

“It’s like taking a Yugo and trying to get off 150 on the freeway,” Kanter said. “Sometimes the wing falls.”

[ad_2]

Source link