[ad_1]

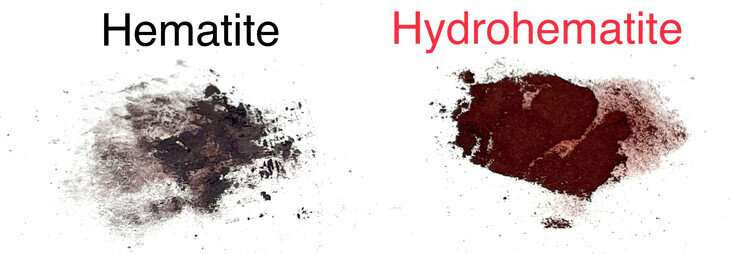

Hydrohematite (right) is a brighter red than anhydrous hematite (left). Credit: Si Athena Chen, State of Pennsylvania

According to a team of geoscientists, the combination of a once-debunked 19th-century identification of a water-carrying iron mineral and the fact that these rocks are extremely common on Earth suggests the existence of a substantial water reservoir. on Mars.

“One of my students’ experiments was to crystallize hematite,” said Peter J. Heaney, professor of geosciences at Penn State. “She found a compound low in iron, so I went to Google Scholar and found two papers from the 1840s where German mineralogists, using wet chemistry, came up with low iron versions of hematite which contained the water.”

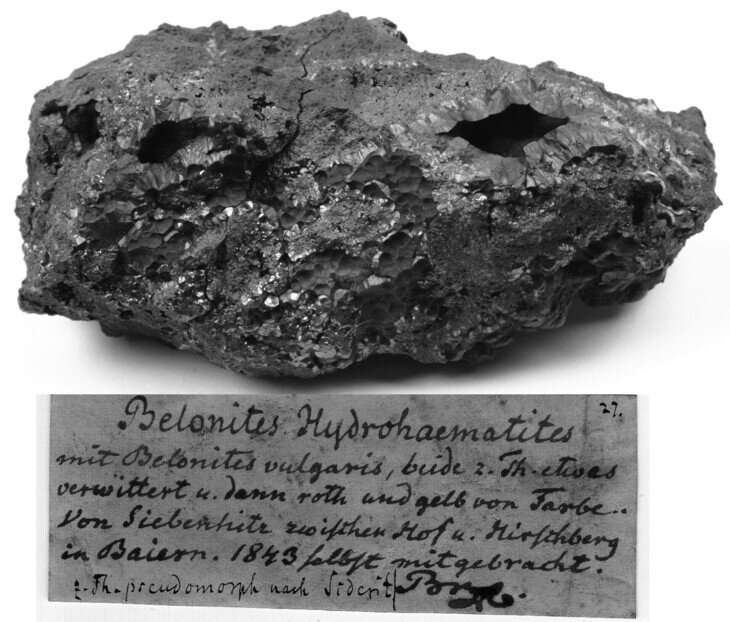

In 1844 Rudolf Hermann named his mineral turgite and in 1847 August Breithaupt named his hydrohematite. According to Heaney, in 1920 other mineralogists, using the then newly developed X-ray diffraction technique, declared these two articles incorrect. But the nascent technique was too primitive to see the difference between hematite and hydrohematite.

Si Athena Chen, a geoscience doctoral student at Heaney, began by acquiring a variety of old samples of what had been labeled as containing water. Heaney and Chen obtained a small piece of the original Breithaupt sample, a sample labeled as turgite from the Smithsonian Institution and, surprisingly, five samples that were in the Frederick Augustus Genth collection at Penn State.

After multiple examinations using a variety of instruments, including infrared spectroscopy and synchrotron X-ray diffraction, a more sensitive and refined method than that used in the mid-19th century, Chen showed that these minerals were indeed light on iron and had hydroxyl – a hydrogen and oxygen group-substituted at some of the iron atoms. The hydroxyl in the mineral is stored water.

The researchers recently proposed in the journal Geology “That hydrohematite is common in low temperature iron oxide occurrences on Earth, and by extension, it can inventory large amounts of water in seemingly arid planetary environments, such as the surface of Mars.”

“I was trying to see what the natural conditions were for forming iron oxides,” Chen said. “What were the temperatures and pH needed to crystallize these hydrated phases and could I find a way to synthesize them.”

She discovered that at temperatures below 300 degrees Fahrenheit, in an aqueous and alkaline environment, hydrohematite can precipitate, forming sedimentary layers.

“Much of the surface of Mars apparently appeared when the surface was wetter and iron oxides precipitated out of that water,” Heaney said. “But the existence of hydrohematite on Mars is still speculative.”

The “blueberries” found in 2004 by NASA’s Opportunity rover are hematite. Although the latest Martian rovers have X-ray diffraction devices to identify hematite, they are not sophisticated enough to differentiate hematite from hydrohematite.

The hydrohematite specimen discovered by German mineralogist August Breithaupt in 1843 with its original label. Credit: Andreas Massanek, TU Bergakademie, Freiberg, Germany

“On Earth, these spherical structures are hydrohematite, so it seems reasonable to me to speculate that the bright red pebbles on Mars are hydrohematite,” Heaney said.

The researchers note that anhydrous hematite – devoid of water – and hydrohematite – containing water – are two different colors, with the hydrohematite being more red or containing dark red streaks.

Chen’s experiments revealed that natural hydrohematite contained 3.6% to 7.8% by weight of water, and goethite contained about 10% by weight of water. Depending on the amount of hydrated iron minerals found on Mars, researchers believe there could be a substantial supply of water there.

Mars is called the red planet because of its color, which comes from the iron compounds contained in Martian dirt. According to the researchers, the presence of hydrohematite on Mars would provide further evidence that Mars was once an aquatic planet and that water is the only compound necessary for all life on Earth.

Glauconitic-type clay found on Mars suggests the planet once had habitable conditions

If Athena Chen et al, Superhydrous hematite and goethite: a potential water reservoir in the red dust of Mars ?, Geology (2021). DOI: 10.1130 / G48929.1

Provided by Pennsylvania State University

Quote: Earth rocks point the way to Hidden Water on Mars (2021, July 29) retrieved July 29, 2021 from https://phys.org/news/2021-07-earthly-hidden-mars.html

This document is subject to copyright. Other than fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.

[ad_2]

Source link