[ad_1]

Key group fossils used to uncover the Eocene-Oligocene extinction in Africa with primates on the left; the carnivorous hyaenodont, top right; rodent, lower right. These fossils come from the Fayum depression in Egypt and are stored in the fossil primate division of the Duke Lemur Center. Credit: Matt Borths, Duke University Lemur Center

Sixty-three percent. This is the proportion of mammal species that became extinct in Africa and the Arabian Peninsula around 30 million years ago, after Earth’s climate changed from swampy to freezing. But we are only finding out now.

Compiling decades of work, a new study published this week in the journal Communications biology reports on a hitherto undocumented extinction event that followed the transition between geological periods called the Eocene and Oligocene.

This period was marked by dramatic climate change. In an inverted image of what is happening today, the Earth has cooled, ice caps have expanded, sea levels have dropped, forests have started to turn to grasslands, and carbon dioxide is rising. become rare. Almost two-thirds of the species known in Europe and Asia at this time have disappeared.

It was thought that African mammals may have gotten away with it unscathed. Africa’s mild climate and proximity to the equator could have been a buffer against the worst of the cooling trend of this period.

Today, thanks in large part to a large collection of fossils housed at the Duke Lemur Center Division of Fossil Primates (DLCDFP), researchers have shown that despite their relatively mild environment, African mammals were just as affected as those in Europe. and Asia. The collection was the lifelong work of the late Elwyn Simons of Duke, who scoured the Egyptian deserts in search of fossils for decades.

The team, made up of researchers from the United States, England and Egypt, examined the fossils of five groups of mammals: a group of extinct carnivores called hyaenodonts; two groups of rodents, anomalies (scaly-tailed squirrels) and hystricognaths (a group that includes hairless porcupines and mole rats); and two groups of primates, the strepsirrhines (lemurs and lorises) and our own ancestors, the anthropoids (apes and apes).

By gathering data on hundreds of fossils from multiple sites in Africa, the team was able to construct evolutionary trees for these groups, identifying when new lineages branched out and time stamping the first and last known occurrence of each species.

Their results show that all five groups of mammals suffered enormous losses around the Eocene-Oligocene boundary.

“It was a real reset button,” said Dorien de Vries, postdoctoral researcher at the University of Salford and lead author of the article.

After a few million years, these groups start to appear again in the fossil record, but with a new look. The fossil species that reappear later in the Oligocene, after the great extinction event, are not the same as those found before.

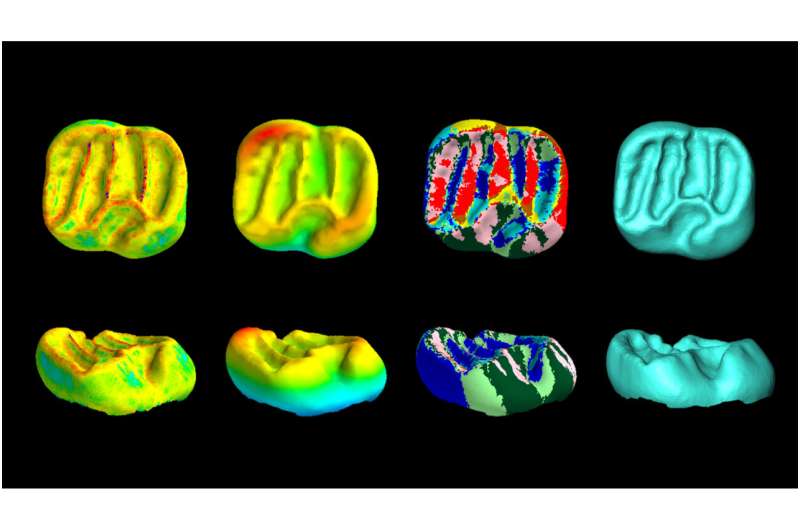

Dental CT scans show that mammalian teeth became less diverse during the early extinction events of the Oligocene. Here is an example of the three-dimensional shape of a tooth from a lower molar from a fossil anomaluroid rodent. Credit: Dorien de Vries, University of Salford

“It’s very clear that there was a huge extinction event and then a recovery period,” said Steven Heritage, researcher and digital preparer at DLCDFP at Duke University and co-author of the article.

The proof is in the teeth of these animals. Molars can say a lot about what a mammal eats, which in turn says a lot about its environment.

Rodents and primates reappeared after a few million years had different teeth. They were new species, which ate different things and had different habitats.

“We see a huge loss of tooth diversity and then a period of recovery with new tooth shapes and new adaptations,” said de Vries.

“Extinction is interesting that way,” said Matt Borths, curator of the DLCDFP at Duke University and co-author of the article. “It kills things, but it also opens up new ecological opportunities for the lines that survive in this new world.”

This decline in diversity followed by an upturn confirms that the Eocene-Oligocene border acted as an evolutionary bottleneck: most lineages became extinct, but a few survived. Over the millions of years that followed, these surviving lineages diversified.

“In our anthropoid ancestors, diversity almost collapsed about 30 million years ago, leaving them with just one type of tooth,” said Erik R. Seiffert, professor and chair of the Department of Integrative Anatomical Sciences at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California, former Simons graduate student and co-lead author of the paper. “This ancestral tooth shape determined what was possible in terms of subsequent dietary diversification.”

“There is an interesting story about the role of this bottleneck in our own evolutionary history,” Seiffert said. “We almost never existed, if our ape-like ancestors had become extinct 30 million years ago. Fortunately, they did not.”

The rapidly changing climate was not the only challenge these few surviving types of mammals faced. As temperatures dropped, East Africa was hit by a series of major geological events, such as volcanic super-eruptions and basalt flooding, huge eruptions that blanketed vast swathes of rock. in fusion. It was also around this time that the Arabian Peninsula separated from East Africa, opening up the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden.

“We’ve lost a lot of diversity at the Eocene-Oligocene borderline,” Borths said. “But the species that survived apparently had enough tools to survive this fluctuating climate.”

“Climate change through geological time has shaped the evolutionary tree of life,” said Hesham Sallam, founder of the Center for Vertebrate Paleontology at the University of Mansoura in Egypt and co-author of the article. “Collecting evidence from the past is the easiest way to learn how climate change will affect ecological systems. ”

Ancient teeth from Peru suggest now extinct monkeys crossed the Atlantic from Africa

Dorien de Vries et al, Generalized loss of mammalian lineage and dietary diversity in the early Oligocene of Afro-Arabia, Communications biology (2021). DOI: 10.1038 / s42003-021-02707-9

Provided by Duke University

Quote: The Climate-Due Mass Extinction No One Has Seen Before (2021, October 7) retrieved October 7, 2021 from https://phys.org/news/2021-10-climate-driven-mass- extinction.html

This document is subject to copyright. Other than fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.

[ad_2]

Source link