[ad_1]

Copyright of the image

Science Photo Library

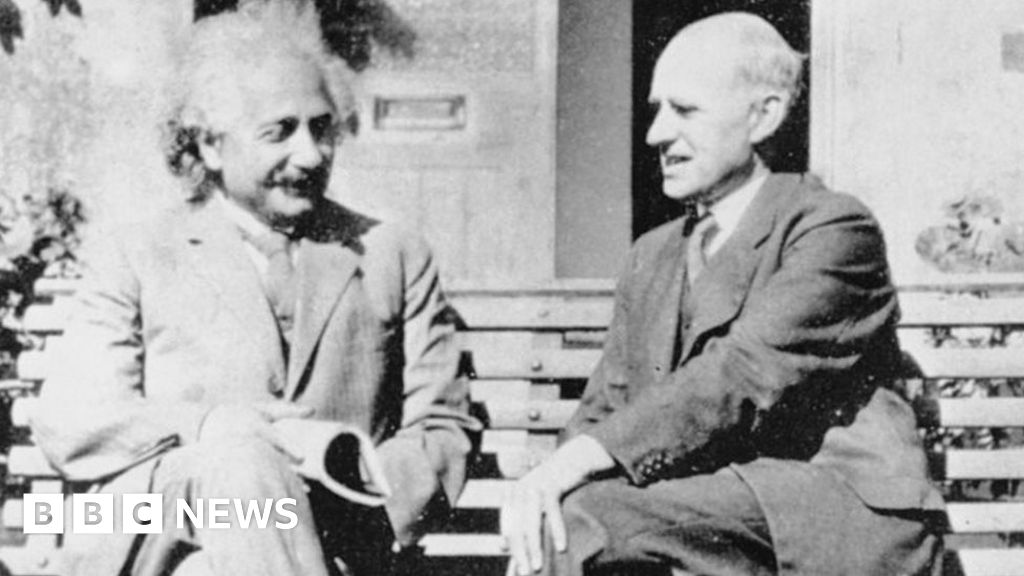

Einstein (left) and Eddington (right) only met for the first time years after the end of Word War One

It is hard to imagine a time when the name of Albert Einstein was not recognized worldwide.

But even after completing his theory of relativity in 1915, he was almost unknown outside of Germany – until the British astronomer Arthur Stanley Eddington was involved.

Einstein's ideas were trapped by the blockages of the Great War, and more so by the vicious nationalism that made science "enemy" undesirable in the United Kingdom.

But Einstein, a socialist, and Eddington, a Quaker, both felt that science must transcend the divisions of war.

It is their partnership that has allowed relativity to cross the gaps and make Einstein one of the most famous people in the world.

- The great idea of Einstein made simple

- Einstein Manuscripts: New Published Documents

Einstein and Eddington did not meet during the war, they did not even send any direct messages. Instead, a common friend in the Neutral Netherlands decided to broadcast the new theory of relativity in Britain.

Einstein was very lucky that it was Eddington, Professor Plumian of Cambridge and officer of the Royal Astronomical Society, who received this letter.

Not only did he understand the complicated mathematics of the theory, but as a pacifist he was one of the few British scientists willing to think of German science.

He dedicated himself to defending Einstein in order to revolutionize the fundamentals of science and to restore internationalism to the scientists themselves.

Einstein was the perfect symbol for that – a brilliant and peaceful German who refuted all stereotypes of war while challenging Newton's deepest truths himself.

Desperate fight to test the theory of Einstein

So, while Einstein was trapped in Berlin, starving behind the blockade and living under government surveillance for his political views, Eddington tried to convince a hostile English-speaking world that an enemy scientist deserved their attention.

He wrote the first books on relativity, gave popular lectures on Einstein and became one of the greatest scientific communicators of the twentieth century.

His books have been on bestseller lists for decades, he has been constantly on BBC radio and has finally been knighted for this work.

Copyright of the image

Science Photo Library

Eddington photographed the solar eclipse May 29, 1919

It was difficult to convince the United Kingdom to be concerned about space-time and gravity, while sub-ships reduced the transport of food. Thousands of young lives have been lost for meager gains in Flanders, Belgium.

Einstein's ideas were not enough. Relativity is strange, with twins aging differently and planets trapped by deformed space.

Eddington needed a definitive demonstration that relativity was true and Einstein was right and that only his international approach could revolutionize science.

His best option was to test a bizarre prediction of Einstein's theory of general relativity.

When light passed near a massive body like the Sun, Einstein said that gravity slightly bent the rays.

This meant that the image of a distant star would be slightly shifted – the star would appear to be in the wrong place.

Einstein predicted a specific number for this change (1.7 seconds arc, or about 1/60 millimeter in a photo). An astronomer would find that difficult to measure, but it could be done.

Unfortunately, as it is normally impossible to see the stars during the day, it is necessary to wait for a total solar eclipse to be able to observe it.

Total eclipses are rare, short and often located in uncomfortable places requiring long trips for European astronomers. Einstein had been trying for years to test this forecast, without success.

Eddington, however, thought that he might be able to make it to the next eclipse of May 1919, visible in the southern hemisphere.

Even with the threat of submarines, no country was better placed than Britain to undertake an expedition aimed at testing Einstein's predictions.

Copyright of the image

Science Photo Library

Frank W Dyson (left) secured funding for Eddington's expedition

Eddington needed a lot of support for that.

Fortunately, he was a close friend of Frank W. Dyson, the Royal Astronomer. Dyson got funding, although even with that money, the war made it difficult to buy the necessary equipment.

Even worse, it was possible that Eddington was not able to participate in the expedition because he was likely to be in jail.

As a Quaker, Eddington was a conscientious objector to the war and refused to participate in the conscription. Many other Quakers have been imprisoned or have done hard labor.

After many unsuccessful calls, it seemed that Eddington would be arrested, but at the last moment he got a waiver (presumably designed by his politically savvy friend, the royal astronomer).

Surprisingly, it was given on the condition that he lead the expedition to test the theory of Einstein.

"Greater moment of life"

The November 1918 armistice allowed the expedition to unfold.

Eddington wanted to ensure that the results of the expedition, whichever they were, carried Einstein to the attention of the world.

So with Dyson, he launched a public relations campaign to spark the enthusiasm of the scientific community and ordinary people.

The newspapers were prepared and ready to account for what Eddington had presented as an epic battle between the British Newton and the Einstein arrival.

Einstein, gravely ill because of the famine of war and seeking to move into a Berlin torn apart by the revolution, knew little.

Instead, Eddington and his colleagues had to test Einstein's prediction almost completely by themselves.

Two teams were sent to observe the eclipse: one in Brazil and one – led by Eddington – on the island of Principe in West Africa.

Copyright of the image

Science Photo Library

Eddington's "comparator" measured changes in the position of stars on telescope glass plates mounted under mobile microscopes

On May 29, 1919 – 100 years ago – these astronomers watched the clouded sky for six minutes to capture the smallest change in stars and reveal the greatest change in our understanding of the universe.

Almost ruined by the weather, equipment malfunctions and steamship strikes, the expeditions reported photographs showing stars displaced by the gravity of the Sun.

After months of intense measurements and mathematics, Eddington had a positive result.

He called it the greatest moment of his life: "I knew that Einstein's theory had withstood the test and that the new perspective of scientific thought had to prevail".

He presented the results at a Royal Society Hall full of scientists and journalists eager to hear who had triumphed, Einstein or Newton (even as Newton's portrait was watching the debates).

The announcement caused a sensation. The president of the Royal Society said that "one of the greatest achievements of human thought".

The next day, The Times newspaper titled "Revolution in Science".

Eddington had perfectly planned the event. Einstein, practically overnight, passed from an obscure scholar to a sage that everyone wanted to know more.

And Eddington gave the audience what he wanted. As the chief apostle of relativity in the English-speaking world, he was the one to whom all newspapers and magazines addressed.

His classes were to drive away hundreds of people. Those who did not only learned the strange physics of relativity, but also Einstein, symbol of international science, able to overcome the hatred and chaos of war.

Einstein himself could barely get out of bed. He heard about the results of a telegram via the Netherlands.

He was delighted that his theory was verified even as he was puzzled by the media storm that suddenly enveloped his life.

Never again could he venture out the door without being addressed by the reporters.

Without Eddington, relativity would not have been proven and Einstein would never have become the icon of genius.

Eddington was Einstein's most essential ally, although they did not meet until years after the end of the war.

Their collaboration was crucial not only for the birth of modern physics, but also for the survival of science as an international community during the darkest days of the First World War.

Matthew Stanley is the author of Einstein's War: How Relativity Conquered Nationalism and Shook the World

[ad_2]

Source link