[ad_1]

As of today (December 3), scientists have 1.8 billion local stars at their fingertips.

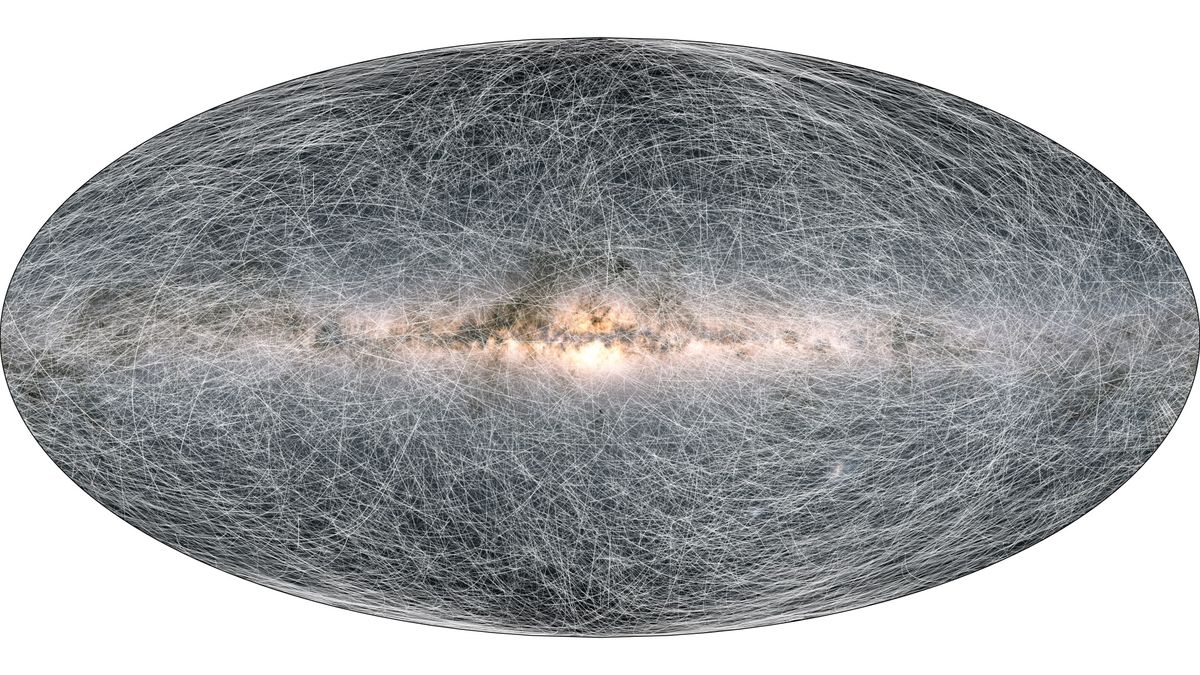

This bonus is due to the European Space Agency Gaia Mission, who spent 6.5 years following the stars in our Milky Way galaxy and beyond. Using observations from the spacecraft, scientists can create an accurate 3D map of the stars and find patterns unfolding across the galaxy.

“Basically all of astronomy benefits in one way or another because it’s very basic data,” said Anthony Brown, astronomer at Leiden University in the Netherlands and chairman of the team at director of the Gaia Data Processing and Analysis Consortium, at Space.com. “It’s a very, very broad fact-finding mission.”

Related: This 3D color map of 1.7 billion stars in the Milky Way is the best ever

The study of 1.8 billion stars is certainly impressive, but the heart of mission science is statistical analysis facilitated by such large amounts of data. “I think the precise number doesn’t really matter that much,” Brown said. “We are still probably only seeing about 1% of all stars in the Milky Way, even with that huge number.”

Although today is the first chance for scientists to access the data publicly, members of the Gaia team have already explored it to perform initial analyzes. One of the results of this work is that scientists measured how solar system accelerates in its orbit of the Milky Way, a tiny phenomenon.

To do this, Gaia studied over a million quasars – shiny objects in the heart of galaxies – located so far away that they shouldn’t appear to be moving. But they do, and in a pattern that points to the center of the Milky Way’s center and reflects all of the different little tugs the solar system experiences from nearby objects.

The result is a value that represents a fraction of a fraction of a meter, measured with even smaller precision, a tiny number that could not be meaningfully calculated until the data is re-released.

“It’s amazing you can do that,” Brown said of the measure.

And this is only the beginning. Today’s data is The third treasure of the Gaia spaceship and includes nearly three years of observations, less than half of what has been collected so far. (The disconnect stems from the sheer mass of data Gaia collects and the processing work that 400 team members across Europe must do to make it public results.) And at least two more data releases are planned. , potentially more if Gaia’s mission is extended to last a full decade.

Among many other research, the previous data release has allowed scientists to track the history of the Milky Way’s formation, Brown said. These measurements identified the Milky Way most recent major merger, about 10 billion years ago. More recently, as the Milky Way slowly tore apart a nearby dwarf galaxy, interactions appear to coincide with bursts of star formation in the Milky Way, another type of galactic form.

Brown pointed to a different finding from previous data to show the kind of science Gaia can facilitate, based on observations from white dwarfs, the super-dense cores of stars like our sun that have lost their outer layers and are running out of fuel.

In Gaia’s measurements of the brightness and temperature of these stars, scientists could identify the brightness levels at which generally dim stars appear to hover a bit before continuing to fade. And that, Brown said, proves that deep in these stars carbon and oxygen crystallize, which scientists have long been waiting for, but couldn’t observe.

“I really like that result because we start off by saying, ‘OK, let’s see how far away these things are,’ and you end up looking in and proving they’re crystallizing,” Brown said. “This was predicted 50 years ago, but this is the first time we can prove it with observations that this has happened.”

And today, scientists have even more powerful data to play with.

the new data is available through the European Space Agency.

Email Meghan Bartels at [email protected] or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

[ad_2]

Source link