[ad_1]

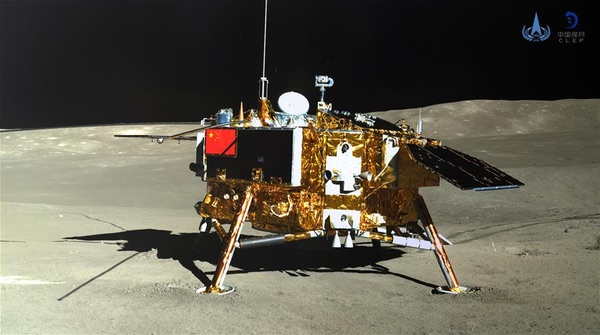

The landing of the Chang-e-4 mission has sparked a new wave of speculation about China's lunar exploration projects, but much of this is unfounded. (credit: CNSA) |

by Dwayne A. Day

Monday, March 11, 2019

![]()

Chinese astronauts were already walking on the moon. In 2005, if you had read many articles about China's space program, you would have noticed several authors claiming that China would land on the moon in 2008, and at least one article claimed that this would happen as soon as 2010. The space stories that began to appear at the time were two common themes: China had an active human program on the moon and a "race" against the United States to send people to the surface of the world. Moon, which was not true. The Space Review articles published more than a decade ago warned of these distortions.

| In 2005, if you had read many articles about China's space program, you would have noticed several authors claiming that China would land on the moon in 2008, and at least one article claimed that this would happen as soon as 2010. |

Unfortunately, today's reportage and pontificate on the Chinese civilian space program is full of similar distortions, which have more to do with writers' prejudices than what is really happening with the Chinese civilian space program. After landing the Chinese probe Chang'e-4 on the far side of the moon in early January, many articles made extravagant statements about the meaning of this event and how it announced China's future activities. . Sometimes, the same authors who made bad statements about China today did the same in 2005.

Opinion articles on the recent Chinese Lunar Landing often fall into several broad categories:

Often these statements overlap or have been expressed by the same authors in different forums. For example, Namrata Goswami wrote in The Space Review that China was planning to create a base on the Moon to extract resources. (See "Why the landing of the moon of Chang'e-4 is unique", The Space Review, January 14, 2019). Mr. Goswami claimed that "a research base on the moon, with an industrial capability to build and support spacecraft using lunar resources, such as water to propel rockets, will reduce the costs of interplanetary travel.

A few days earlier, Dr. Goswami had published an opinion piece in The Washington Post describing recent events as a space race that the United States was losing, claiming that Americans were blind to reality. This article asserted that "the United States is disorganized in terms of space and can not be a serious challenge to China's long-term plans for this area. Neither the American people nor the US military seem to perceive the importance of what China is strategically doing in the Earth-Moon space. They see this from the perspective of their own experience of the Cold War, assuming that the motivations of Chinese ports resemble those of the United States today – for global prestige and the simple fact of ticking boxes – when it is not the case. "

She added: "The issue is not just the prestige here on Earth: it's about whether the future of space exploration, resource development and of colonization will be democratic or dominated by the Chinese Communist Party and the People's Liberation Army of China. " Notably, Goswami presented only two options: that the Chinese seek global prestige "and simply tick … boxes" or, in his opinion, they pursue "resource development and colonization". But what some may see as American disorganization, others will interpret the normal constructive chaos of a competitive entrepreneurial capitalist system that has produced amazing technological breakthroughs in recent years, such as reusable rockets and cubesat constellations.

| The Chinese civil space program, which is much more public, has thus become a sort of Roschach test for writers: they see their fears and preoccupations, and equate civil space activities with military power and strategic capabilities, even when they do not. there is little evidence to support these interpretations. . |

These opinion articles are about China civil space programs, not their increasingly successful military space programs. Because the Chinese military space program is surrounded by secrecy, outside writers know little. The Chinese civil space program, which is much more public, has thus become a sort of Roschach test for writers: they see their fears and preoccupations, and equate civil space activities with military power and strategic capabilities, even when they do not. there is little evidence to support these interpretations. . Many authors have never even considered other explanations for Chinese civil space activities, for example the fact that China is pursuing a vast program of exploration and space sciences – exactly what the Chinese say they do.

Around and around we go

This idea that China's efforts in the civilian space indicate a harmful intent has emerged for two decades now, since China launched its manned space flight program. The first Shenzhou spacecraft was launched in November 1999, followed by several other unmanned satellites, which led Shenzhou 5 to put Yang Liwei into orbit in October 2003. During this first period, it was common for Western press the military nature of Shenzhou, based on the fact that it was run by the People's Liberation Army. But beyond vaguely disturbing warnings, they never explained what military advantage China would get with a piloted spacecraft, especially since the United States and Russia had long since concluded that military space missions with crew were useless. The United States canceled its Laboratory of Manned Orbits in the late 1960s and the Soviets canceled their Almaz military space stations in the early 1980s.

There was actually a practical explanation for the PLA's participation in Shenzhou: it was one of the few organizations in the Chinese government to be able to manage major technology projects. Some authors, however, have attempted to present China's capability for manned spaceflight – particularly after the accident in Colombia in 2003, when the US space shuttle was immobilized – posed the problem of the slowness of the program. China. In almost two decades of Shenzhou flights, China has only completed six crew missions. Each flight has demonstrated significantly improved capabilities. But when the flights took place two or three years apart, they did not correspond to a running ability or Chinese menacing space flight capability. Thus, some authors quickly turned to a new interpretation of Chinese space flight: China was going to send humans on the Moon.

After President George W. Bush announced in 2004 his intention to send the Americans back to the moon, some writers began looking for new evidence that China was also seeking to send human beings to the moon. (See "Mysterious Dragon: Myth and Reality of the Chinese Space Program," The Space Review, November 7, 2005) The Vision for Space Exploration Calling for a Moon Landing by 2018, Journalists Have Sometimes claimed to have discovered China's clues. to land a human on the moon by 2017, "beating" the Americans, ignoring the fact that Americans were there already decades earlier. (See "Red Moon, Black Moon." The Space Review, October 11, 2005).

Around the same time, from 2005 to 2007, China became much more public on its plans for manned space flights and space science. Chinese space officials have begun to discuss the country's plans to carry out more human missions in the next decade, leading to the commissioning of a multi-segment space station in Earth's orbit. by 2020. They have also begun to announce future projects in Earth Sciences, Astrophysics, Solar Science and Global Exploration. In 2010, China announced plans for a major civil space science effort. It made perfect sense: Chinese leaders want the country to be a world power and be seen as a global power, not only militarily and economically, but also technically and scientifically. This requires demonstrating civil space capabilities and participating in international scientific conferences.

In retrospect, if we look at China's efforts in the humanities and space sciences over the past 15 years, it is remarkable open the Chinese government and space science organizations were on their plans. In a series of public presentations beginning around 2006, Chinese officials explained their interest in the gradual establishment of manned space flight capabilities, with the aim of setting up a space station in low Earth orbit for years. 2020. They were much more transparent than the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

However, despite the relative openness of Chinese officials about their projects, some authors have chosen to stick to Chinese Internet reports about Chinese lunar projects, proving that China is planning to send humans to the moon. as part of a "race" with NASA, ignoring or distorting the evidence that they have found. And these are not just writers: members of Congress have also warned against a "race" towards the moon with China. In the fall of 2005, Congressman Ken Calvert, chair of the House Space and Aeronautics subcommittee, told a reporter from Daily report and defense of the aerospace: "I've talked to a number of people who know a lot more about this subject than I do, [about] Some things may still be classified, but they think the Chinese are probably ready to get there sooner. In March 2006, another congressman said: "We have an ongoing space race and the American people are totally unaware of all this. (See "China, Competition and Cooperation," The Space Review, April 10, 2006) This discussion of China's "race" to the moon has continued for several years. In November 2007, Reuters announced that a Chinese scientist had said that China would land a man on the moon by 2017. It was a deformation of the return mission of lunar robotic samples announced by China.

| Chinese leaders want the country to be a world power and be seen as a global power, not only militarily and economically, but also technically and scientifically. This requires demonstrating civil space capabilities and participating in international scientific conferences. |

At about the same time, it became common for some writers to claim that China had a human lunar program, despite frequent Chinese references to their plans to spend the 2020s exploiting their space station in low Earth orbit. Although some Chinese officials have indicated that they are evaluating large rockets for possible future human lunar missions, they also indicated that it was unlikely that a decision regarding the future would be forthcoming. sending humans on the moon be taken before the late 2020s, after China had operated its space station and gained experience. with theft of human space of longer duration. In addition, the Chinese authorities have sometimes expressly stated do not in a race with the United States. According to an expert based in China based in the United States, it is not because they fear losing, but because they learned the lessons of what happened with the Soviet Union and the American Strategic Defense Initiative in the 1980s, when the Soviets ended up spending a huge amount of money in response to a program that never seriously threatened them.

There were explanations for some of these misleading reports. One of the obvious reasons was the bad translations: people saw "mission on the moon in 2017" and did not see, or mis-translated, the parties about the fact that it was d & # 39; a robotics mission. Another reason is that the Chinese media have experienced an explosion of new entrants, many of which are little more than tabloid reports. Over the last decade, a considerable amount of content has been produced for the Internet in China and few ways to understand the reliability of many sources. Often it was an Internet version of the "phone" children's game (which the British call "Chinese whispers"), where a story is distorted as a story is told – the first time that "robotics" is no longer about discussing a lunar Chinese mission, it quickly turns into "human lunar program".

The people who wrote and pontificated a major problem – they insert their own agenda in their interpretation of what they saw. At the beginning of Vision for Space Exploration, one of the common goals was to try to use the "threat" of a potential Chinese human lunar mission to incite people to support NASA's plan to send humans back on the planet. Moon.

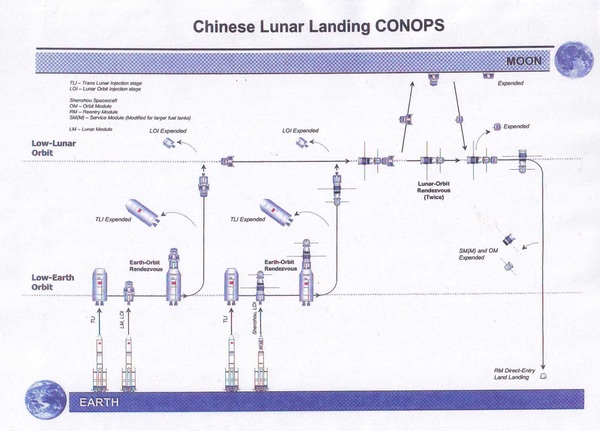

The people of the West have demonstrated a remarkable ability to see what they want to see, even when it is not there. In 2008, a NASA official presented a theoretical chart showing how China could possibly organize a mission to the Moon using many of its existing assets and avoiding the use of a large launcher. (See "The new path to space: India and China enter the game," The Space Review, October 13, 2008) In this case, not only did a NASA official use a potential mission of the Chinese Moon to get a propaganda benefit, but US critics of NASA's lunar plans have exploited this hypothetical mission architecture as "evidence" that NASA did not need a large rocket Ares V to send astronauts back to the moon and that she could do things in the Chinese way. In the end, none of these rhetorical statements were sustainable: it was clear then that China do not planning to send humans to the moon so soon, the "threat" would be exposed as empty.

A 2008 NASA map depicting how China could pose humans on the moon with the help of the Long March 5 rocket. (Credit: NASA) |

No matter where you go, you're there

After long observations, the Chinese space program makes it clear that the Chinese are generally doing what they say they will do. But this poses two challenges. The first challenge is to understand what the Chinese are officially saying about their future civilian space plans. The second challenge is to objectively interpret the plans of the Chinese civilian space. The most effective way to determine what the Chinese are planning is to look for official Chinese officials and statements from space. A single scientist who makes a statement, or a Chinese website that makes a statement, is not enough.

| China's important participation in a major conference on global science in America indicates that China wants to participate in scientific discussions and be taken seriously as a scientific leader. |

People living outside of China mistakenly assume that a Chinese scientist can not speculate or talk about potential future space missions without their statements having been formally approved by the government. This is not true, and many examples of scientists offering their own opinions and speculation without official approval have been numerous. For example, several Chinese scientists have talked about the objective of extracting helium-3 on the moon, that they have clearly taken over Western media, and that is certainly not an official policy of China. (See "The Helium-3 Incantation," The Space Review, September 28, 2015)

What we have also seen over the years is that Chinese space officials have spoken at international conferences on their human spaceflight and space science projects, demonstrating increasing mastery of PowerPoint. During several appearances over the last decade, they described their future plans for manned spaceflight in general, although they often do not provide detailed information on missions until after the end of the mission.

The cover of a recent issue of BBC magazine Scientific focus is part of the latest media campaign aimed at playing a perceived race towards the Moon involving China. |

Race in place

Chinese space officials also presented their robotic lunar plans and have already demonstrated a clear model for these lunar missions. For example, Chang'e-3 was the first lander and mobile mission in China, with a relief spacecraft apparently partially built at the time of the first mission. Once Chang'e-3 was successful, China then changed the Chang'e-4 plan to achieve a new set of goals. Chang'e-5 is expected to be China's first lunar sample return mission scheduled later this year. Chang'e-6 is the alternative and, if the first mission succeeds, China will be able to use Chang'e-6 to bring back samples of the far side of the moon. The success of Chang'e-4 also prompted the Chinese to formally announce their intention to proceed with the Chang'e-7 and 8 agreements, apparently following the same set of upstream / downstream decision rules. The first mission will be to evaluate the resources on the lunar south pole. If that succeeds, Chang'e-8 will assume a more ambitious mission. Thus, China has shown a methodical and highly logical path for lunar science and exploration, the kind of long-term plan that American lunar scientists envy.

Despite China's cautious, methodical and long-standing plans, the theme of "race" continues to appear more and more in the Western press as the first resort of lazy writers. More recently, the BBC print magazine Scientific focus has a cover story that says "A new race to the moon has begun", with "Moon" in red letters. What no one seems to tell us is that China's Lunar Sample Return Mission, Chang'e-5, was first publicly revealed over 10 years ago and is actually two years old. delay on the initial plan. If China "runs", it does so very deliberately and telegraphs its movements.

Although some writers outside of China have attempted to link the lunar robotics program of this country to a plan to explore and exploit lunar resources, or to develop militarily useful space capabilities, their proofs are slim, which requires to ignore substantial evidence is part of a scientist program. For many years, the Chinese have been discussing these scientifically-based lunar missions and say they plan to send robotic missions to Mars as well. In 2018, dozens of Chinese planetary scientists presented their findings at a scientific conference in Houston, and some plan to present it again next week. Their wide participation in a major conference on global science in the United States indicates that China wants to participate in scientific discussions and be taken seriously as a scientific leader.

Why is it important? Because effective decision making, and any potential US response, should not be based on false or distorted assessments of what is really happening. At a conference on China's space program held in Washington in the fall of 2005, several expert observers of Chinese military and space programs noted that at the time, the Chinese had tried to read everything they could about the American space program. The problem was that they also tended to believe everything they read. The same thing happened on the American side, and unfortunately, this tendency to believe that everything is still true in some writers. But there is an old saying that when you hear hooves, think of horses, not zebras. Alas, too many writers on the Chinese civilian space program hear what they want to hear, see what they want to see and do not focus on what is really there.

Note: We are temporarily moderating all under-committed comments to cope with an increase in spam.

<! –

->

[ad_2]

Source link