[ad_1]

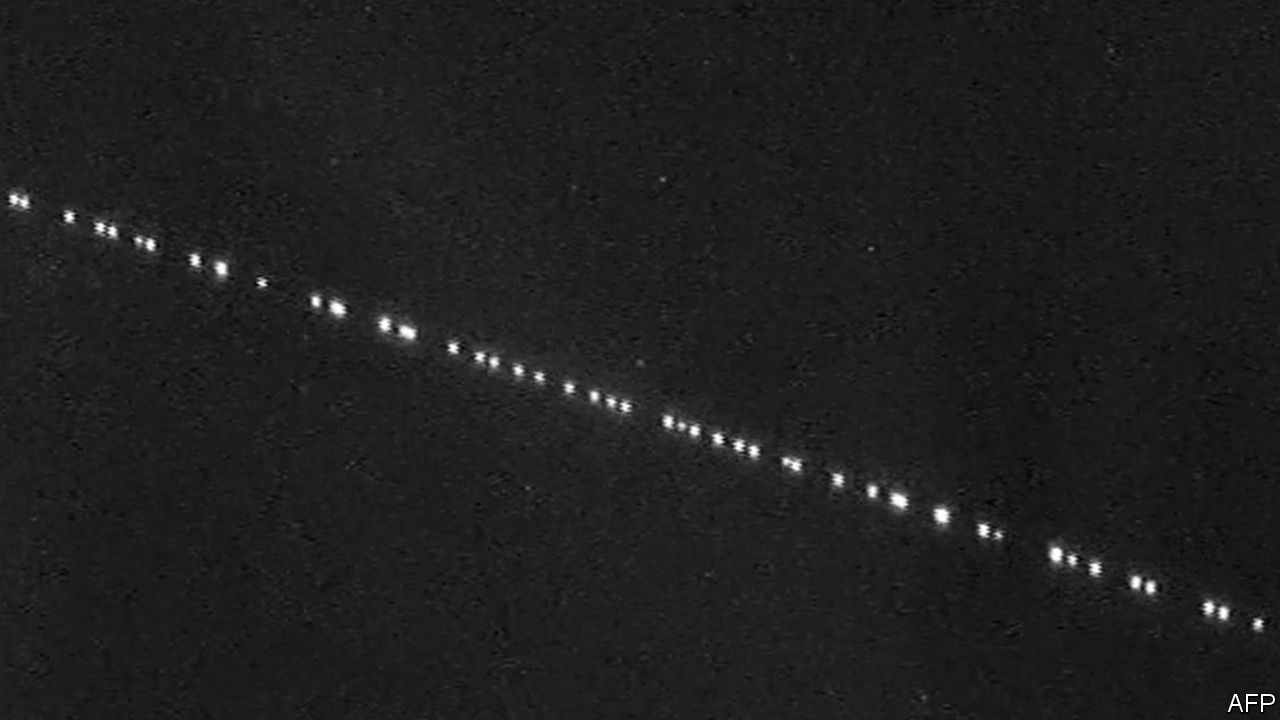

& # 39; TWAS ENOUGH a show: a train of bright spots moving in the sky, mostly bright like Polaris, the star north. These are not new astronomical objects, however. Rather, it was the first installment of satellites for Starlink, a project to provide Internet access around the world. These were launched into orbit May 24 by SpaceX, an American rocket company.

Seeing satellites from the ground to the naked eye is not new. But astronomers (professionals and amateurs) were surprised and dissatisfied with the number and brightness of Starlink satellites. A number of them went on Twitter to sound the alarm and post photos and videos of burning birds. Their concern was that these satellites and their successors could change the night sky forever. If the first 60 members of the Starlink network were already causing significant light pollution, was their reasoning bad if the full constellation of 12,000 aircraft had been launched?

For those who like to look at the night sky for fun, it would surely be sad because it would more than triple the number of man-made objects in the firmament and further degrade the natural beauty of the heavens – a beauty already reduced many places by light pollution of the ground. For those who study the universe in a scientific way, it may be more than sad. In some cases, this could be a threat to employment.

Preliminary analysis shows, for example, that almost all the images of the large synoptic telescope in Chile, nearing completion and intended to photograph the entirety of the available sky every few nights when it is operational, could contain a satellite track. These can be deleted, but each fix destroys valuable data. It is possible that some experiments, such as regular observations of the variation of the behavior of astronomical objects, are no longer feasible.

Optical astronomers must be nervous about Starlink. For radio astronomers, its impact could be even more serious. The mode of operation of the satellites necessarily forces them to return to Earth radio signals that will all be more powerful than any signal from deep space. This can be taken into account to a certain extent by knowing the frequencies broadcast by the satellites and adjusting them accordingly. But the extent to which radio observatories will affect the damage will depend on the satellites' ability to limit their emissions in these frequencies, which remains to be seen.

SpaceX boss Elon Musk firstly dismissed astronomers' concerns, saying this weekend that there were already 4,900 satellites in orbit, which people notice about 0% of the time. Starlink will only be visible by a careful look and will have an impact of ~ 0% on the progress of astronomy. However, during his later exchanges, he gave a more comprehensive tone. Starlink would avoid frequencies associated with radio astronomy, he said, and if satellite orientations were to be adjusted to minimize solar reflection during critical astronomical experiments, this could easily be done. In addition, when the first Starlink satellites returned to their operational configuration after the weekend, their brightness was reduced – even if they activated occasionally when they were crossing the sky, probably at night. because of the reflections of their large solar panels.

Mr. Musk also appeared in his tweets to suggest that Starlink's goals outweigh the disadvantages. "The greatest benefit is to potentially help billions of economically disadvantaged people. That said, we will ensure that Starlink will have no material effect on astronomy discoveries. We care a lot about science. His statement is well founded. The problem, observes Mark McCaughrean, senior adviser for science and exploration at the European Space Agency, is that there has been little public discussion on the subject. From his point of view, the night sky is a common good that risks appropriation in the name of private interest. That this appropriation serves the greater good should at least be the subject of debate.

For the moment, astronomers are planning to perform other simulations of the potential impacts of Starlink and other communications satellite networks planned by companies such as OneWeb. But even when this work is done, it is unclear what they can really do for SpaceX and its competitors to listen to their concerns, as there is no legislation regulating the impact of satellites on the night sky.

The US Federal Communications Commission is very interested in how satellites use the available radio spectrum and what happens to them once their work is done. But that's it. With the mega-constellations of future communications satellites, it may be time for this to change, and governments (not just the United States) are becoming more involved in the use of the sky.

[ad_2]

Source link