[ad_1]

The flu and coronavirus ‘twindemic’ feared by public health officials has so far not materialized.

The flu typically kills tens of thousands of Americans and can cause hundreds of thousands of hospitalizations during the winter season. But this year it has failed almost entirely in the Bay Area – a necessary stroke of luck as coronavirus cases, hospitalizations and deaths escalate out of control statewide.

“Influenza is hardly present in northern California at this point,” said Dr. Randy Bergen, pediatric infectious disease specialist at Kaiser, who is also the clinical manager of the influenza vaccination program. Northern California. “Our hospitals are always full during the winter, and in normal years it’s because of the flu. It’s a very abnormal year, but it’s because of a different respiratory virus.

A typical year sees a positive rate of around 20 to 40% for hospital flu tests, Bergen said, but this year doctors don’t really see such cases. About one in four patients who come to the hospital with respiratory symptoms are positive for the coronavirus, but the other three are for something else: not the coronavirus, not the flu, and not the respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, another common respiratory virus this accounts for thousands of deaths each year in the United States, but it has also completely disappeared from the map.

Dr Gary Green, an infectious disease specialist at the Sutter Medical Group of the Redwoods in Santa Rosa, says doctors have only seen sporadic cases of influenza A and influenza B there – with influenza A growing in the past. Last 3-4 weeks.

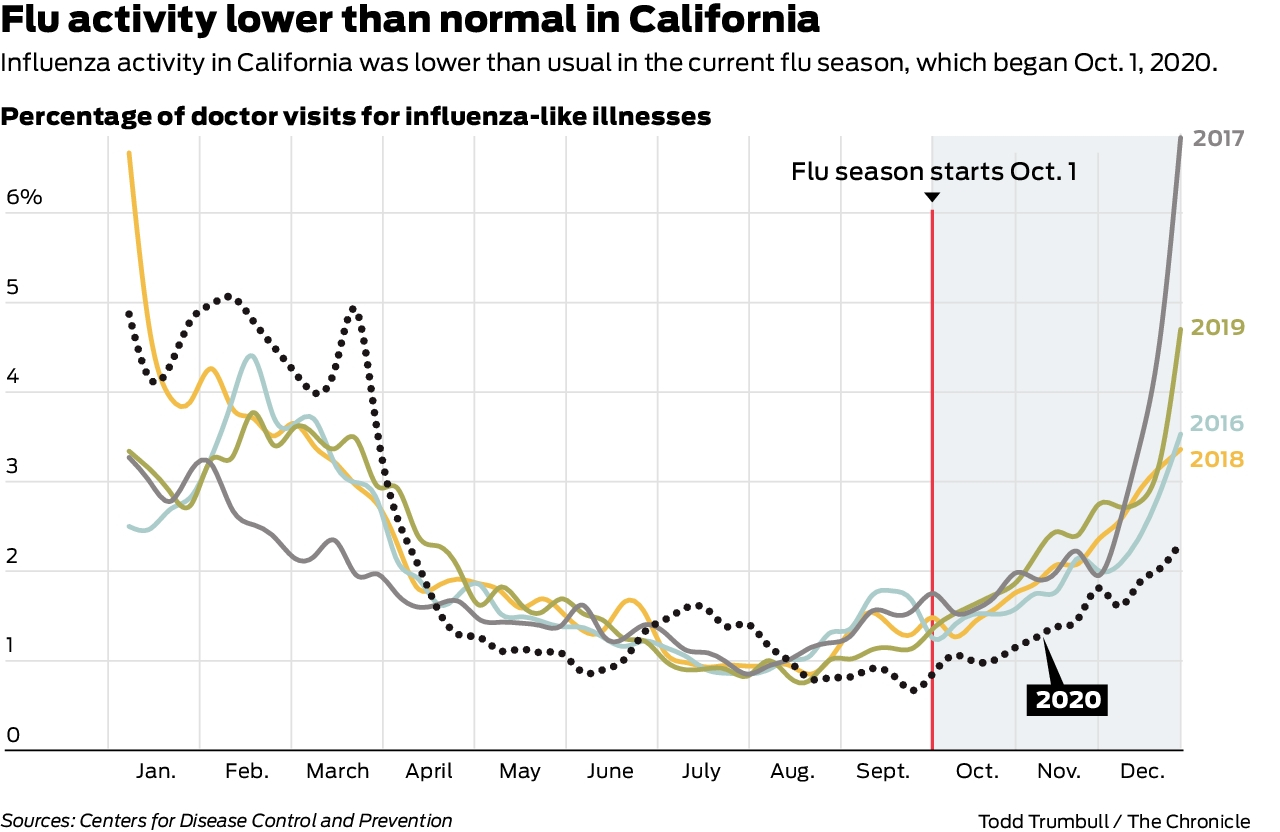

The minimum flu season in the Bay Area reflects what has already been demonstrated in the southern hemisphere, in places like Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, where the flu season has taken place without the flu itself. This same trend is now being reflected in the United States and California, which are seeing much lower influenza activity rates this season than usual.

According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracking doctor visits for flu-like symptoms as a percentage of total visits, California has hovered between 1% and 2% since the start of the season on the 1st. October. Over the past four years, this share has varied between 3.5% and 6.5% at that time.

Reports from the California Department of Public Health’s influenza surveillance program, which tracks influenza in weekly reports, paint an even more startling picture of an influenza season that has slipped under the radar.

Take the first week of January, for example, which marks halfway through the flu season, when cases and hospitalizations typically peak. During the 2019-2020 season, this week saw widespread influenza activity statewide, with more than 26.9% positive laboratory influenza tests, 19 outbreaks and 70 deaths for the season at this point. . Hospitalizations were above expected levels.

The 2020-2021 report couldn’t be more different, with 0% hospital admissions for influenza, a 0.3% positive laboratory influenza test rate, and zero epidemics since the fall. Seven deaths have been reported, but a map of California shows virtually no influenza activity in the state.

So, what happened?

So far, some experts have linked this year’s quiet season to a robust rollout of the flu vaccine, which has seen people getting vaccinated en masse, some for the first time and much earlier than usual. But that still doesn’t explain the appeasement, said Dr Lawrence Drew, a retired virologist who headed UCSF’s clinical virology lab.

“The best we have ever seen in the United States for vaccine cooperation is 50-60% and that wouldn’t be enough to explain it, and it wouldn’t explain RSV,” he said.

Some people, Drew said, also attributed the quiet season to an idea called viral interference, when an organism that has been infected with one virus somehow resists infection with a second virus. But it also seems unlikely, he said, because they are usually similar viruses – and influenza, SARS COV-2 and RSV are not similar.

What is by far the most likely explanation, say Drew and other experts, is that pandemic public health masking and social distancing measures are extremely effective in preventing the spread of influenza and RSV – even more than for the spread of the coronavirus.

There is a scientific basis for this: Studies have shown that SARS COV-2 is much more transmissible than the major seasonal respiratory viruses, which include influenza and RSV. A new variant of the coronavirus, which has made its way to the United States and California, is even more contagious, with some figures pointing to a 70% increase in transmissibility.

According to the CDC, influenza activity is unusually low across the country this season. Although California has now surpassed the national rate of influenza-like illness, such spikes are not uncommon during influenza seasons. They could also be linked to growing outbreaks of coronavirus cases in the state, mainly in southern California, which officials have in part attributed to more lax adherence to public health guidelines. (At this time of last year and at the start of the current flu season, California’s average was lower than the nation’s.)

At the end of December, visits to the doctor for ILI in California accounted for 2.3% of the total visits, while the national rate was 1.6%. Drew suspects the Bay Area is doing better than other parts of the state – and the country – that may not be following public health guidelines as rigorously.

According to Bergen, Kaiser’s pediatric infectious disease specialist, there could be another “wild card” factor for the slow flu season: Flu seasons almost always start in schools, and most Bay Area schools are still distant or hybrid, with a mask. usury and social distancing.

The rollout of the coronavirus vaccine in California and the United States has started slowly, and COVID-19’s long year is likely months away from being under control. And flu season doesn’t always peak in December or January, Bergen said. As a result, if people stop wearing masks, socially distancing themselves, and following hand hygiene, a twindemic could still be on the horizon.

Drew’s long-term vision is even more urgent. If people come out of this flu season and approach the next like it never happened – avoiding masking, social distancing, etc. – all this security will be reversed. The guidelines that have helped us avoid the flu this year, he says, are essential to continue.

“In a few years – five or 10 or maybe just one – we’re going to have an influenza pandemic,” Drew said, adding that variants are likely to emerge for which scientists won’t have vaccines. “Everybody knows it. … There is no doubt about it. We’re late. “

Annie Vainshtein is a writer for the San Francisco Chronicle. Email: [email protected] Twitter: @annievain

[ad_2]

Source link