[ad_1]

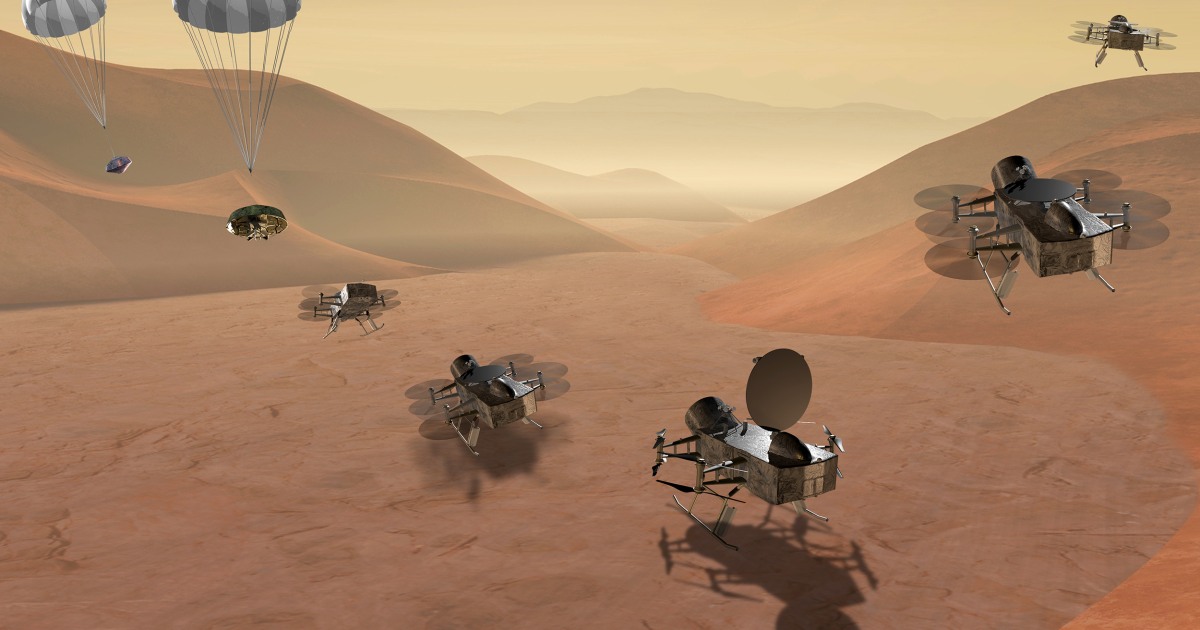

The hazy sky of Saturn’s Titan moon is the next destination for the increasing use of flying drones to explore the solar system. This time, scientists are preparing not only to jump but to climb up to 13,000 feet and travel hundreds of kilometers in search of evidence of ancient microbial life.

This is a major step beyond the success of NASA’s Ingenuity drone on Mars, and it means that Earth’s flying robots will play an increasingly important role in the exploration of our solar system.

“The ingenuity was a technological demonstration,” said Alex Hayes, associate professor and director of the Center for Astrophysics and Planetary Science at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. “You can now expect sequels to extend this technology to real science missions using flight. “

In July, Hayes and his colleagues detailed the scientific objectives of the Titan probe, called Dragonfly, which is expected to launch in 2027 and arrive around Saturn by 2034. Its main objectives will be to search for chemical traces of microbial life on the planet. moon and to study the “methane cycle” – a much cooler analogue of the water cycle here on Earth – that shapes its landscape.

Dragonfly has been in the works for over a decade, roughly since the Cassini mission to the Saturn system deployed the Huygens lander to the surface of Titan in 2005.

Titan’s surface is obscured by the thick haze of its dense atmosphere, but the brief Huygens mission revealed tantalizing glimpses of its landscape, with dunes, dried up riverbeds, and lakes of liquid hydrocarbons.

Unlike Mars, where the very thin atmosphere and relatively high gravity make flight difficult, the atmosphere on Titan is about four times as dense as ours, although unbreathable, and its gravity is a little less than on our moon.

“Titan is the easiest place to fly in the solar system,” said professor and planetologist Jason Barnes of the University of Idaho in Moscow, Idaho, and one of the principal investigators of the Dragonfly mission.

The half-ton Dragonfly lander will spend several days in one spot, performing science experiments while its batteries recharge from a radioisotope thermoelectric generator, then fly up to an hour or more to a new location.

Dragonfly will do most of its science on the surface, but its eight rotors will allow it to fly much higher and further during its initial 32-month mission than Ingenuity.

“We really see ourselves as a lander,” Barnes said. “We spend 99% of our time on the ground. “

Key to the science goals of the Dragonfly mission is to sample the soil of Selk Crater, which was created by a meteorite impact on Titan perhaps millions of years ago.

Titan’s surface is so cold – minus 290 degrees Fahrenheit – that all the water there is frozen as hard as rock, though there are vast lakes of methane and ethane.

Like some of Saturn and Jupiter’s other moons, however, Titan is believed to have liquid water under its crust, and the impact of Selk may have forced some of that liquid to the surface for some time.

Groundwater may be the best place on Titan for microbial life to evolve, so Dragonfly will take samples from the bottom of the crater to look for its frozen chemical traces, Barnes said.

The flying lander will also be able to study the composition of the dunes on Titan’s surface – the type of terrain a rover would get stuck in – and the weather in Titan’s atmosphere, including its methane showers.

Barnes explained that the chemicals that now exist on Titan are similar to chemicals that existed on Earth in its very early days, and the Dragonfly mission will help scientists understand them better.

The new details of the Dragonfly mission come just weeks after the extraordinary success of NASA’s Ingenuity drone on Mars.

“The ingenuity and the whole Perseverance project exceeded expectations,” said Athena Coustenis, who leads planetary rover research for the French government and whose team worked on the mission cameras.

Ingenuity only had to perform five test flights. But it has now completed 12 flights and is exploring new ground for the Perseverance rover it has paired up with.

The success of the small drone, which weighs just 4 pounds, has renewed attention to plans for even larger flying probes – like the 60-pound Mars Science Helicopter, a six-rotor design that could explore the Red Planet wirelessly. using a rover. .

Coustenis, who was not involved in the recent Dragonfly study, noted that only Earth, Mars, Titan and Venus have atmospheres dense enough for flying vehicles and that two Soviet missions, Vega 1 and Vega 2, had explored with hit the clouds of Venus with balloons in 1985.

While planetary rovers can only travel at relatively slow speeds over limited distances, flying probes could cover great distances over distant planets and moons while avoiding dangerous terrain.

Titan was the “next obvious destination for flying machines” like Dragonfly, she said, but there were also proposals to explore both Titan and Mars with fixed-wing drones and even balloons – although balloons in the thin Martian atmosphere would have to be very large and could only carry small experimental payloads.

[ad_2]

Source link