[ad_1]

With social media, it's easy to find reports from unknown sources around the world. But it can often be difficult to know which sites present the truth, which have a political bias and spread lies.

A new research project at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Qatar Computing Research Institute's computer science and artificial intelligence lab aims to use machine learning to detect sites that focus on facts and those that are most likely to generate erroneous information.

"If a website has already published false information before, there is a good chance it will do it again," said Postdoctoral Associate MIT CSAIL's Ramy Baly, lead author of the website. an article on technology, in a statement.

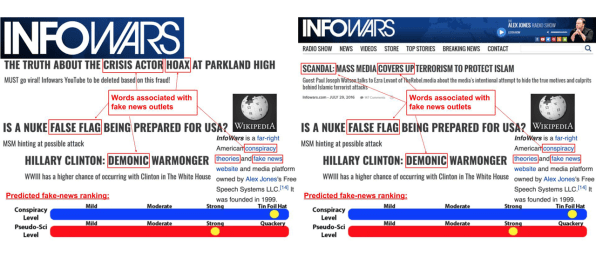

The tool uses an automatic learning technique, called support vector machines, to learn how to predict how media organizations will be ranked by Media Bias / Fact Check, an organization that records the level of factual content and political biases in the media. thousands of news sites. It takes into account the actual content of articles on the sites, as well as external factors such as the presence of Twitter on the site, the structure of its online domain name and the way it is described on Wikipedia.

"The most useful source of information to judge both factuality and prejudice is to be the actual articles," said Preslav Nakov, senior scientist at QCRI, during an interview.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, fewer factual sites used more hyperbolic and emotional language than those with more factual content. In addition, according to Nakov, sources of information with longer descriptions on Wikipedia tend to be more reliable. The online encyclopedia can also verbally indicate that sources of information are suspicious, such as references to prejudices or a tendency to spread conspiracy theories, he says.

"If you open Breitbart's Wikipedia page, for instance, you'll read things like" misogynist "," xenophobic "," racist "," says Nakov.

Separately, sites with more complex domain names and URL structures were generally less reliable than sites with simpler names. Some of the more complex URLs were sites with longer addresses that essentially imitated familiar addresses with simpler domains.

Researchers focused on tracking the reliability of whole news outlets rather than individual stories, partly in the hope that the algorithms could be more effective at handling a whole body of work than short messages. A system that categorizes entire sites can also be helpful in helping readers evaluate new content on the site, even if it has not been studied by human-social content verifiers like Facebook who use more more. Fact checkers could also use algorithm notation to evaluate cases where different sites report differently on the same subject, suggests Nakov.

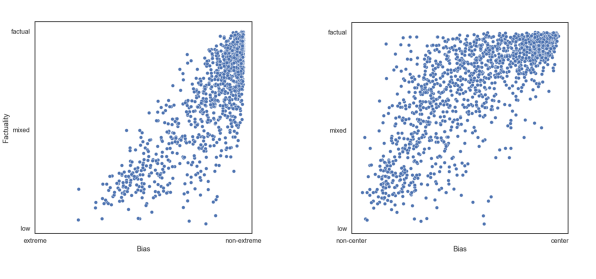

When presented with new media, the system was accurate at about 65% to detect whether it had a high, medium, or low level of reality and at 70% to detect whether it was leaning to the left, to the right or in the center. The researchers plan to present the document in a few weeks at the conference "Empirical Methods on Automatic Language Processing" in Brussels.

Research is far from the only project currently underway to combat misinformation: the Defense Advanced Research Projects has funded research on the detection of falsified images and videos, and other researchers have looked at how 'teach people to spot suspicious information.

In the future, researchers at MIT and QCRI plan to test the English-language system in other languages and see how it behaves with biases other than left and right, such as the detection of new religious or laymen in the Islamic world. The group also planned an application that could offer users an overview of the reports from various political perspectives.

[ad_2]

Source link