[ad_1]

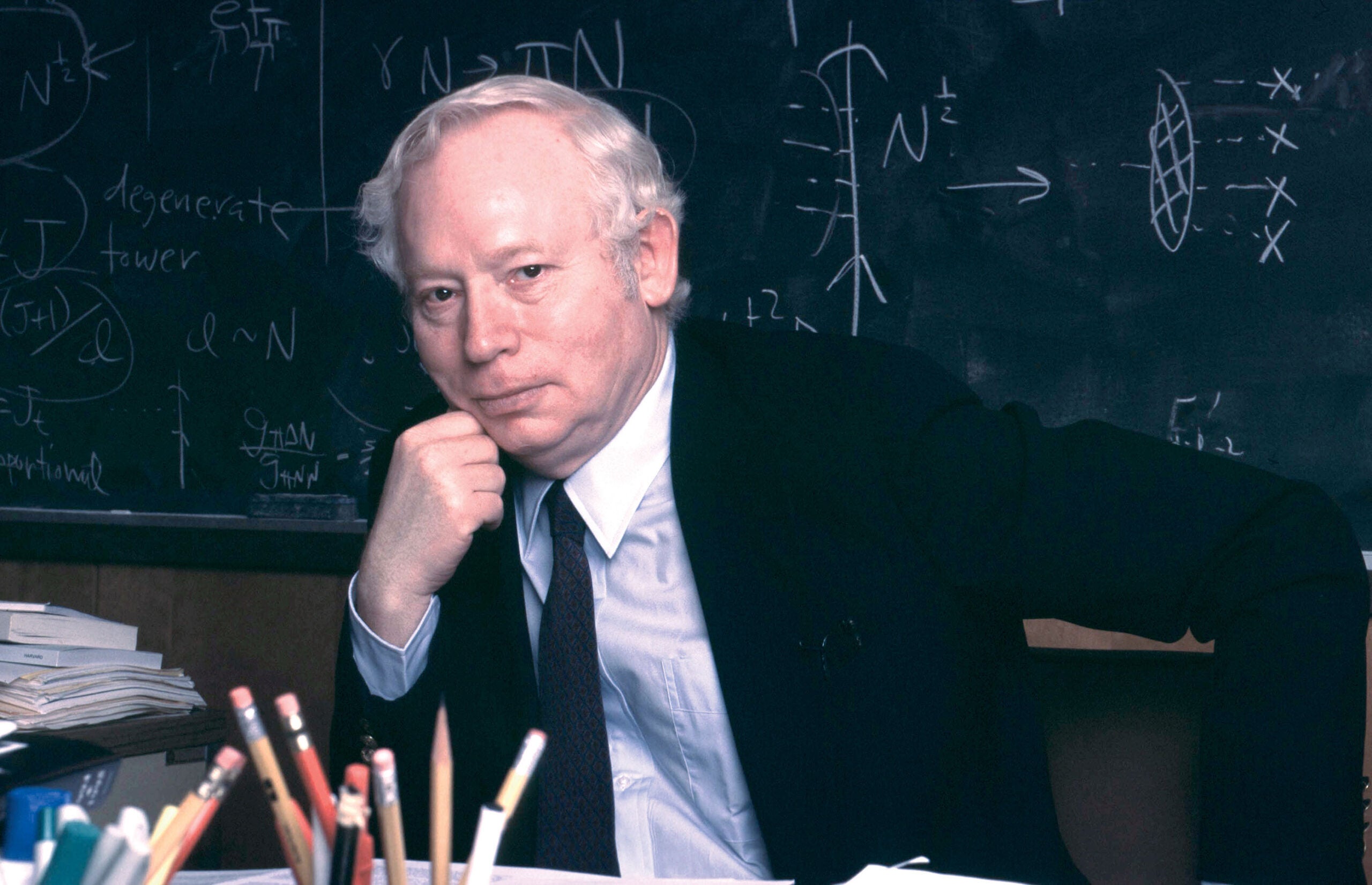

AUSTIN, Texas – Nobel laureate Steven Weinberg, professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Texas at Austin, has died. He was 88 years old.

One of the most famous scientists of his generation, Weinberg was best known for helping to develop a critical part of the Standard Model of particle physics, which dramatically improved humanity’s understanding of how everything in the world universe – its various particles and the forces that govern them – relate. A faculty member for nearly four decades at UT Austin, he was a beloved teacher and researcher revered not only by scientists who marveled at his concise and elegant theories, but also by science enthusiasts of the world who read his books and searched for him in public appearances. and conferences.

“The death of Steven Weinberg is a loss for the University of Texas and for society. Professor Weinberg has unraveled the mysteries of the universe for millions of people, enriching the human concept of nature and our relationship with the world, ”said Jay Hartzell, president of the University of Texas at Austin. “From his students to science enthusiasts, from astrophysicists to public policy makers, he has made a huge difference in our understanding. In short, he changed the world.

“As a world-renowned researcher and faculty member, Steven Weinberg has captivated and inspired our UT Austin community for nearly four decades,” said Sharon L. Wood, president of the university. “His extraordinary discoveries and contributions in cosmology and elementary particles have not only strengthened UT’s position as a world leader in physics, they have changed the world.”

Weinberg held the Jack S. Josey – Welch Foundation Chair of Science at UT Austin and won several science awards, including the 1979 Nobel Prize in Physics, which he shared with Abdus Salam and Sheldon Lee Glashow; a national science medal in 1991; the Lewis Thomas Prize for the Scientist as a Poet in 1999; and, last year, the Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics. He was a fellow of the National Academy of Sciences, the Royal Society of London, the British Royal Society, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the American Philosophical Society, which awarded him the Benjamin Franklin Medal in 2004.

In 1967, Weinberg published a seminal paper explaining how two of the four fundamental forces in the universe – electromagnetism and the weak nuclear force – relate as part of a unified electroweak force. “A Model of Leptons,” barely three pages, predicted the properties of elementary particles that at that time had never been observed before (the W, Z, and Higgs bosons) and theorized that “neutral weak currents” dictated the way whose elementary particles interact with one another. Subsequent experiments, including the discovery in 2012 of the Higgs boson at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in Switzerland, would confirm each of his predictions.

Weinberg has used his fame and his science for causes close to his heart. He has always been interested in the fight against nuclear proliferation and briefly served as a consultant for the United States Agency for Arms Control and Disarmament. He advocated for a superconducting supercollider project with LHC capabilities in the United States – a project that ultimately did not receive funding in the 1990s after it was planned for a site near Waxahachie, Texas. . He continued to be an ambassador for science throughout his life, for example, teaching students at UT Austin and participating in events such as the 2021 Nobel Prize Inspiration Initiative in April and the Texas Science Festival. in February.

“When we talk about science as part of the culture of our time, we had better integrate it into that culture by explaining what we do,” Weinberg explained in a 2015 interview posted by Third Way. “I think it’s very important not to write to the public. You should keep in mind that you are writing for people who are not trained in math but who are just as smart as you are.

By showing the unifying links behind weak forces and electromagnetism, previously believed to be completely different, Weinberg delivered the first pillar of the Standard Model, the half-century-old theory that explains particles and three of the four fundamental forces of the universe. (the fourth being gravity). As essential as the model is to helping physicists understand the order that governs everything from the first few minutes after the Big Bang to the world around us, Weinberg, alongside other scientists, continued to dream of a “theory final “which would be concise and effective. explain current unknowns about forces and particles in the universe, including gravity.

Weinberg has written hundreds of scientific papers on general relativity, quantum field theory, cosmology, and quantum mechanics, as well as numerous articles, reviews, and popular books. His books include “To Explain the World”, “Dreams of a Final Theory”, “Facing Up” and “The First Three Minutes”. Weinberg has often been asked in media interviews to reflect on his atheism and its connection to the scientific ideas he has described in his books.

“If there is no point in the universe that we discover by the methods of science, there is a point that we can give to the universe by our way of living, by loving ourselves, by discovering things about nature, creating works of art, “he once told PBS.” Although we are not the stars of a cosmic drama, if the only drama we play in is that that we are inventing as we go along, it is not entirely despicable that faced with this universe without love and impersonal, we make a little island of warmth and love, of science and of art for ourselves .

Weinberg was originally from New York, and his childhood love of science began with a gift of a chemistry set and continued by teaching himself calculus while a student at the Bronx. High School of Science. The first of his family to attend college, he received a BA from Cornell University and a PhD from Princeton University. He did research at Columbia University and the University of California at Berkeley, before joining the faculty of Harvard University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and, since 1982, UT Austin.

He is survived by his wife Louise Weinberg, professor of law at UT Austin, and their daughter Elizabeth.

[ad_2]

Source link