[ad_1]

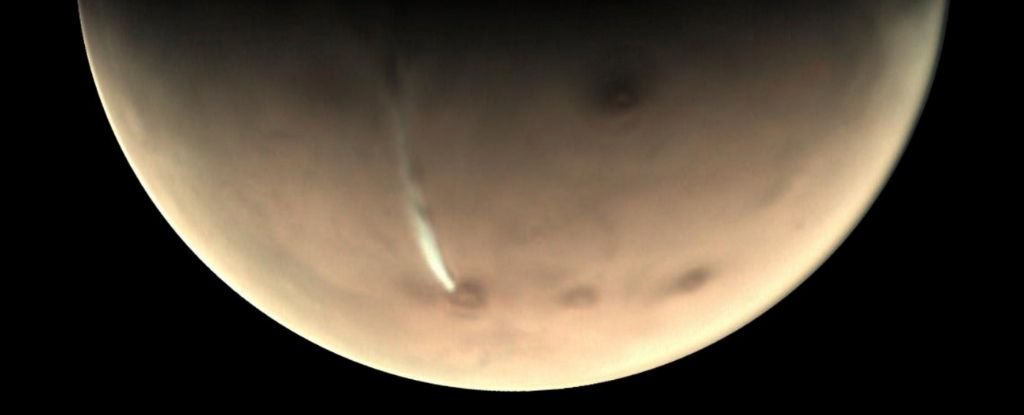

In 2018, a camera aboard the Mars Express mission saw a strangely long and wispy cloud floating on the surface of the Red Planet.

From a distance, the 1,500-kilometer (930-mile) trail of fog almost looked like a plume of smoke, and it appeared to emerge from the top of a long-dead volcano.

Looking at the archived images, the researchers quickly realized that this had been happening for some time. Every few years in spring or summer, this curious cloud returned, before disappearing again. The Ephemeral Plume was filmed in 2009, 2012, 2015, 2018 and again in 2020.

A recently published study has now detailed the reasons why this unfathomably long cloud continues to come and go on Mars. To do this, the researchers compared the high-resolution observations of the 2018 plume to other archived observations, some of which date back to the 1970s.

This is the story of the cloud. Each year, around the beginning of spring or summer in the southern Martian hemisphere, the elongated cloud of Arsia Mons begins to take shape.

At dawn, the dense air from the base of the Arsia Mons volcano begins to rise up the western slope. As temperatures drop, this wind expands and the moisture it contains condenses around dust particles, creating what we call here on Earth an orographic cloud.

Every morning, over the course of several months of observations, the researchers saw this process repeat itself. At about 45 kilometers altitude, the air begins to expand, and for about 2.5 hours the cloud is pulled west by the wind, at a speed of 600 kilometers per hour (380 mph), before to finally break away from the volcano.

At its largest, the plume can reach 1,800 kilometers in length (over 1,100 miles) and 150 kilometers in width (almost 100 miles). By noon, when the Sun is at its peak, the cloud will have completely evaporated.

Ice clouds aren’t exactly unusual on Mars, but clouds over Arsia Mons continue to form in the summer when most of the others disappear. In fact, most of the time this specific volcano has a cloud above it while others around it do not – but only under certain conditions does it spread out in a long streak. (Each year, at the onset of winter, this cloud can also spiral.)

Profile of the elongated cloud of Arsia Mons. (ESA)

Profile of the elongated cloud of Arsia Mons. (ESA)

So if this long plume occurs daily for a period of time each year, why do we only have sporadic observations of it?

Researchers say this is because many cameras orbiting Mars only occasionally fly over this region in the morning, and sightings are usually planned, meaning we often take pictures of this cloud just by chance. .

Fortunately, an old camera still aboard the Mars Express mission – the Visual Surveillance Camera (VMC) that has the power of a 2003 webcam – has an advantage that the new technology does not.

“Even if [the camera] has low spatial resolution, a wide field of view – essential for getting a big picture at different local times of the day – and is ideal for tracking the evolution of an entity both over a long period of time and in small increments of time, ”explains astronomer Jorge Hernández Bernal of the University of the Basque Country in Bilbao, Spain.

“As a result, we were able to study the entire cloud over many lifecycles.”

The study represents the first detailed exploration of the Arsia Mons cloud, and although scientists say it has properties similar to orographic clouds on Earth, its size is enormous and its dynamics quite vivid compared to what we see on our own planet.

“Understanding this cloud gives us the exciting opportunity to try and replicate the formation of the cloud with models – models that will improve our knowledge of climate systems on Mars and on Earth,” says astronomer Agustin Sánchez-Lavega, also of the University of the Basque Country. .

Now that we know when the cloud appears, it also allows us to point other, more powerful cameras in orbit to the right place at the right time, giving us a more precise overview. The next photos may not be too long.

The study was published in the Geophysical Research Journal.

[ad_2]

Source link