[ad_1]

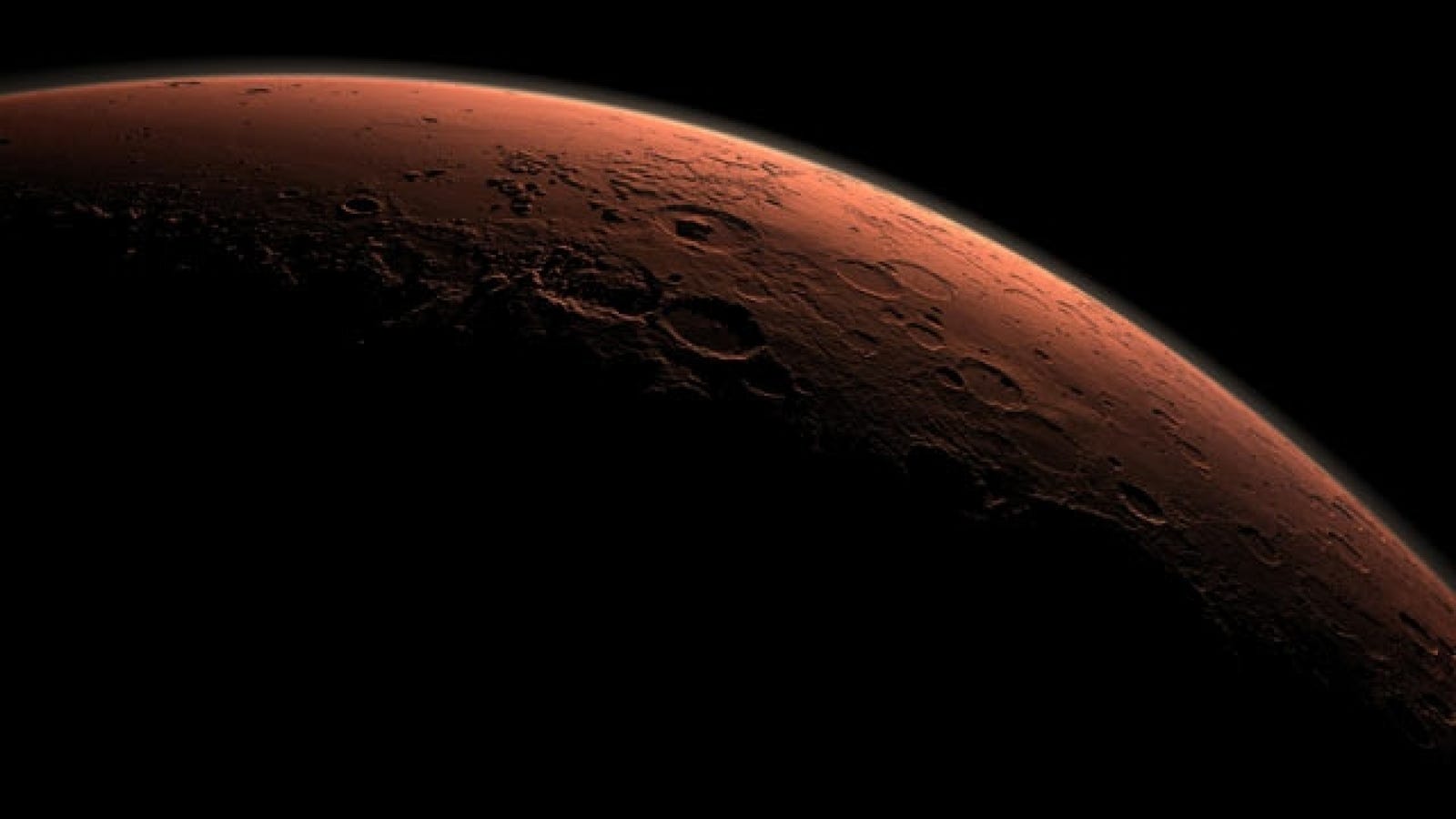

A research team proposes a major philosophical shift in our thinking about the spread of terrestrial microbes in space and on Mars in particular. Believing that interplanetary contamination is "inevitable," the team argues that future Martian settlers should use microorganisms to reshape the red planet – a proposal that all experts find extremely premature.

In an article published last month in FEMS Microbiology Ecology, microbiologist Jose Lopez, a professor at Nova Southeastern University in Florida, and colleagues, W. Raquel Peixoto and Alexandre Rosado, of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, proposed a philosophies that underlie the space exploration and planetary protection policies with regard to the spread of microorganisms in the space.

Rather than worry about the contamination of foreign celestial bodies – which NASA and other space agencies are careful to avoid – Lopez and his co-authors argue that we should deliberately send our germs into space and that the spread of our microbes should be part of a broader colonization strategy to tame the climate on Mars. The researchers put forward a key argument: the prevention of contamination is a "near-impossibility", as the authors say in the study.

"The microbial introduction should not be considered accidental but inevitable."

A policy change like this would go against conventional thinking in this area. Some of the experts we spoke with said that the protocols currently in place to prevent us from contaminating another planet were probably working to the best of our knowledge, and we should not just give up so easily. In addition, the experts said that a lot of scientific work had yet to be done on Mars and elsewhere before starting to consider this irremediable possibility.

Currently, the wider scientific community agrees on the need to prevent microbial contamination of planetary bodies such as Mars. NASA, ESA and other space agencies sterilize their instruments carefully and at a high cost before launching them to nearby celestial targets.

The philosophy of global protection, or PP, dates back to the late 1950s and the establishment of the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR), established by the International Council of Scientific Unions. COSPAR, among others, develops recommendations and protocols designed to protect the space of our microbes. In the same vein, the UN's Outer Space Treaty, which has been signed by more than 100 countries, specifically states:

States Parties to the Treaty pursue space studies, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, and explore them in a manner that avoids their contamination as well as adverse changes to the Earth's environment resulting from the introduction. extraterrestrial material and, where appropriate, adopt the appropriate measures for that purpose. If a State Party to the Treaty has reason to believe that any activity or experience planned by it or by its nationals in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, would cause an interference potentially detrimental to the activities of other States Parties in the course of peaceful exploration the use of outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, it shall undertake appropriate international consultations before proceeding to such activities or experiences.

The main reason behind this thinking is that our germs can potentially contaminate important scientific areas of the solar system, thus impairing our ability to detect indigenous microbial life on Mars and in other worlds. Finding traces of DNA or RNA on Mars, for example, does not automatically mean that they come from the Earth, because these molecules could represent a fundamental and ubiquitous element of the evolution of the Universe. Perhaps even more problematically, it is to be feared that invading terrestrial life will remove an extraterrestrial ecosystem even before we have a chance to study it.

For their part, Lopez and his colleagues believe that it will be almost impossible to prevent our germs from infiltrating the places we are exploring. So we could have a rational discussion about how best to use microorganisms to our advantage. Specifically, the authors refer to the terraforming perspective, to the hypothetical practice of geoengineering a planet to make it more Earth-like.

Considering the ancient history of Earth as a precedent, the authors recognize the essential role that microorganisms play in promoting habitability on our planet, including oxygen production, gas regulation like carbon dioxide, methane and nitrogen, as well as the decomposition of organic and inorganic materials.

"Life as we know it can not exist without beneficial microorganisms," Lopez said in a NSU press release. "They are here on our planet and help define symbiotic associations – the coexistence of many organisms to create a greater whole. To survive on sterile planets (and as far as travel to date tells us), we will have to carry useful microbes with us. [to Mars]. It will take time to prepare, discern and we do not advocate a rush to vaccinate, but only after rigorous and systematic research on Earth. "

The key to their argument is the recognition of our transition from explorers to settlers. This life could exist or have existed elsewhere in the solar system does not seem to be the case, say the authors. "The lack of discovery or proof of life among the 70 or so space missions and spacecraft that have left the orbit of the Earth indicates a single presence of life in our immediate solar system," they write.

Lopez and his colleagues argue that if we want to take the colonization of Mars seriously, we will have to take into account the role played by our microbes. But spreading germs around Mars should not be done indiscriminately and without careful foresight, they say.

"Instead, we are considering a deliberate and measured research program on microbial colonization, realizing the limitations of current technologies. We therefore advocate a conservative calendar of microbial introductions into space, while realizing that human colonization can not be separated from microbial introductions ".

To this end, the researchers propose a proactive vaccination plan, or PIP. Such a plan would be put in place prior to any long-term mission and would involve the selection of promising microbial candidates. Dangerous microbes would be eliminated, while only the "most productive" microbes would be included for future missions, as the authors write:

If humanity is seriously considering colonizing Mars, another planet or one of the nearest moons to come, we must identify, understand and send the most competitive and beneficial pioneers. Choose or develop the most sustainable microbial [species] or communities can use deliberations, systematic research and current data, rather than sending random bacteria hitchhiking to space stations.

Extremophiles – microbes capable of living in the most hostile environments of the Earth – would be the first microbes scattered on Mars, probably buried a few meters underground to protect them from frost and radiation on the surface.

But as the authors admit, "total control of a complete inventory of [species] and their genomes sent into space can never be realistically achieved, "and the recovery of the microbes once sent may be impossible. "In other words, we will never have total control or knowledge of the process, nor will we stop it once we start.

The authors gave no indication of when the first microbes should be planted on Mars or how long it will take the microorganisms to produce the desired effects, assuming that it works. This is an open question, for example, if microbes, even extremophiles, can operate on the Martian surface where the exceptionally low atmospheric pressure hovers around a measly 0.7 kPa, which is not too far from the conditions reigning in space. The low gravity on Mars as well as the intense solar radiation that hits the surface complicate the image even more.

Humans will never colonize Mars

The suggestion that humans will soon be setting up animated and sustainable colonies on Mars is something …

Read more

But even if it works, the time needed should discourage even the most optimistic Martian colonists. On Earth, these processes have required hundreds of thousands, even millions of years, of microbial mixing of patients (eg, oxygen production via photosynthesis by cyanobacteria).

Bruce Jakosky, a professor of geoscience at the University of Colorado and Mars terraforming prospects expert, said the authors proposed "very important changes" to the global protocol for protecting the planet, as he wrote in an email addressed to Gizmodo.

"These [recommendations] seem to go against decades of approach we have taken in PP, "said Jakosky. "I am happy to be able to discuss in more detail how the PP should be implemented and the need to modify it, but I am concerned about suggestions that recommend such changes without thoroughly examining their implications with an impartial vision. "

Physicist Todd Huffman of Oxford University said that the authors made a logical mistake by saying that it was impossible to completely sterilize a spacecraft on Earth. So we should not even try. Huffman believes that we should definitely try and that we have a very good chance of succeeding our planetary protection systems, whether through protocols on Earth, to the devastating effects of deep space exposure or the harsh conditions already in place on Mars. .

"Since 1976, many probes have landed on the surface of Mars. All have been submitted, up to now, to COSPAR's extreme sterilization protocols, "Huffman wrote to Gizmodo in an e-mail. "And to date, none of them have detected microbes or traces of Martian microbes – or the Earth. This means that the COSPAR protocols actually work. Thus, not only their argument does not hold, but their claim that it is impossible to keep contaminants out of a planet such as Mars has proved unfounded until it present, "he said. To which he added: "My opinion is that if it does not break, do not fix it. The COSPAR protocols seem to keep insects away from the Earth of Mars, as we study this planet for the presence of native organisms. We should not play with them unless we want to tighten them further. "

Huffman does not disagree that we could possibly want to introduce microbes into Mars in the manner described by the authors, but it would be "a serious scientific mistake to relax the COSPAR protocols on any world that we still have to determine. as dead. asking us to keep "our insects out of Mars, Europe, Enceladus and maybe even Titan," he said. "At least for the moment."

"We must follow the equivalent of the Hippocratic oath on planetary protection:" Above all, do no harm. "

Steve Clifford, senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute, said the new document raised serious concerns. In the end, he believes that the potential consequences of an error in easing global protection standards "far outweigh the short-term gains." We could possibly contaminate Mars, he said, but by then we must follow the equivalent of the Hippocratic oath of global protection. : – Especially do not hurt. & # 39; "

"I think the potential contamination of an extraterrestrial biosphere is a serious ethical problem because it is a legacy that we are always carrying with us," Clifford told Gizmodo in an email. . Like Huffman, he fears that terrestrial germs complicate our ability to do science on Mars and says there is no reason to believe that current planetary protection systems are not working.

"If life evolved on Mars or the oceans of the subsurface of the frozen moons of the outer planets, it probably survived on those bodies for billions of years," said Clifford. "The detection of life on one of these bodies would have a deep meaning in our understanding of the prevalence of life throughout the universe."

With respect to claims that the implementation of global protection protocols is too costly, Mr. Clifford stated that the associated additional costs, which generally represent approximately 20% of the cost of the mission is worth it.

"As we explore the potentially liveable environments of our solar system, we need to determine – as definitively as possible – whether an indigenous life is present, before sending human beings there," Clifford said. "And if these environments turn out to be lifeless, the need to meet the current global protection standards evaporates. However, if we discover life, then I think we need to have a serious discussion that weighs our desire to colonize and use the resources of the solar system with the ethical concern to bring about the potential extinction of the very first examples of extraterrestrial life. they found.

At the same time, he does not believe that there is some sort of overt fate to colonize the solar system before we have had the opportunity to conduct a thorough search for extraterrestrial life, "that this research will take 50 years or more centuries ". he said. Until then, "there are many lifeless places in the solar system, such as the Moon and asteroids – that humans can explore, colonize and extract resources," said Clifford.

Lopez and his colleagues have obviously found a sore point. None of the experts we spoke to had any major objections to the use of microbes in the process of colonization and terraforming at any given time. Rather, they have been upset by the statement that we are about to move from the exploration phase to the colonization phase and that we should start mobilizing our resources – and our microbial assets – accordingly.

As we approach a time when we are able to send people to the red planet, this debate will undoubtedly continue to be lively.

[ad_2]

Source link