[ad_1]

From the shores of Florida to the Japanese islands, from the Midway Atoll to the south of Australia, an unprecedented ecological regeneration could be underway. Reef-building coral, which is increasingly threatened in the overheated waters of the tropics, is trying to survive by migrating to subtropical climates that meet its temperature requirements.

The coral reefs of the tropics seemed doomed. Bleached by marine heat waves, suffering from widespread dieback and stuck to the bottom of the sea, they have no obvious outcome since the oceans are warming up. Some experts say that they will be gone by mid-century, the first major damage caused to the climate emergency by the ecosystem.

But the news is not totally sinister. It turns out that young corals can be surprisingly mobile, able to move in ocean currents, if their homes become inhospitable, and move towards more equal waters. "I think there is a glimmer of hope for them," says Nichole Price of Maine's Bigelow Laboratory for Marine Sciences, lead author of the first global study on their sporadic recovery.

Marine ecologists report the migration of tropical corals to subtropical regions, which is part of a wider "tropicalization" of ocean ecosystems, species seeking colder waters far from the equator. As they struggled in their former habitat, they proliferated between 20 and 35 degrees north and south of Ecuador, young refugee corals creating new reefs hundreds of miles from home.

With corals in motion, the map of tropical corals that build reefs around the world is being redrawn.

Price warns that migration does not offset the tropical decline. The percentage of new establishment of corals in subtropical regions, while encouraging, is going down. "Many more corals are lost near the equator than migrating to the subtropics," she says. Overall, recruitment has declined by 82% over the last four decades. But, even in this case, cleaning may not be imminent.

In southern Japan, for example, at 33 degrees north, more than 70 species of coral now occupy most of Tatsukushi Bay. In the United States, staghorn and elkhorn corals extend around the Florida Peninsula in the Gulf of Mexico. And in Australia, corals seem to migrate south from the Great Barrier Reef to the New South Wales coast, around Sydney, at 30 degrees south.

This has been going on for a while, but until now no one has done the complete picture yet. Price's six-country study, released last month, reveals that with coral in motion, the map of tropical coral that is building the world's reef is being redrawn.

His study has two main results. First, the bad news: the recruitment of new young corals on tropical reefs has dropped by 85% since the 1970s. Even healthy-looking reefs simply do not replicate. But the good news is that there has been a 78% increase in recruitment to study sites outside the tropics. Coral recruitment has been "moving," Price concludes.

Corals grow alongside algae in the temperate waters of southern Japan.

Soyoka Muko University / Nagasaki

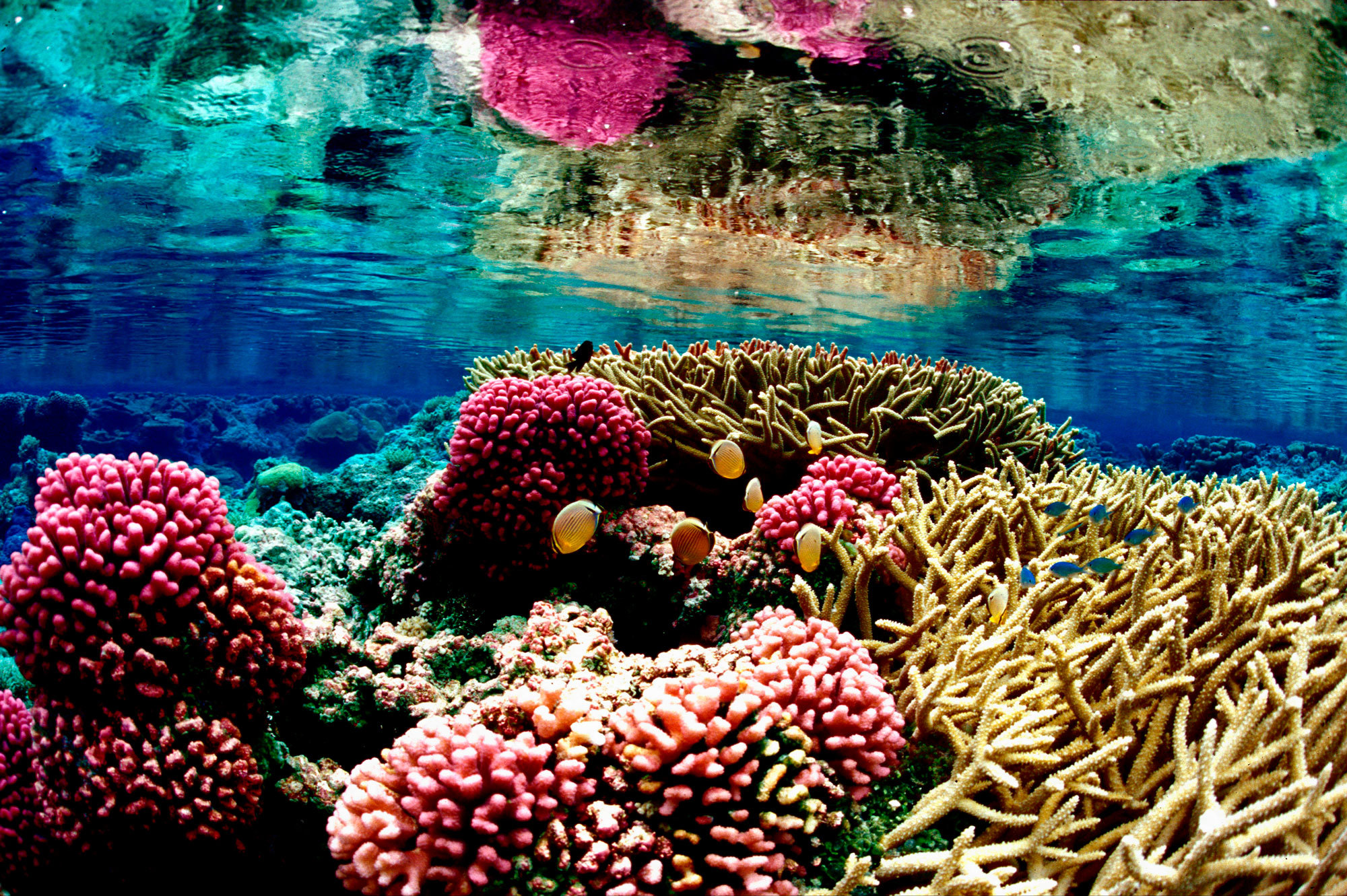

Tropical coral reefs are among the most complex ecosystems in nature. Immersed a few meters from the surface of the sea, they are bathed in sunshine, which favors their ecology. Most reefs are home to an impressive number of creatures: worms and snails, limpets and conches, crabs and eels, sea cucumbers and sharks, feeding and eating.

The reefs grow in the form of platforms extending from the shores or over submerged mountains to the seabed. The Great Barrier Reef off Australia has a length of over 1,400 km and took about 500,000 years to reach this size. The Enewetak Atoll in the Marshall Islands extends over half a kilometer and is the product of some 60 million years of growth.

The corals that make up these reefs are soft-fleshed creatures, akin to sea anemones. But they produce hard exoskeletons that accumulate in billions and blend into rocky bottoms, creating reefs. Their famous kaleidoscopic color is provided by microscopic algae that live in translucent corals in a symbiotic relationship. In return for shelter, seaweed provides corals their main source of food.

Coral reefs occupy only about 1% of the world's oceans – from the Caribbean to the "coral triangle" centered on Indonesia, in Southeast Asia, but they are home to about a quarter of marine species. They have survived destructive fishing, pollution, the extraction of building materials, the anchors of cruise ships and even nuclear bomb tests. But climate change has turned out to be their nemesis.

Significant coral bleaching in the Kimberley region of Western Australia in April 2016.

Morane The Nohaic / Coral CoE

If the water temperature rises just 2 degrees Fahrenheit above normal for more than a few weeks, the stressed coral expels its algae and the multicolored reefs become a ghostly white. This "bleaching" has reached epidemic proportions and is among the most obvious signs of ecological decline due to global climate change.

Bleaching does not have to be deadly. But if the waters do not cool enough to allow the return of symbiotic algae in a few weeks, the corals die of hunger. And death can happen faster if the temperatures are high enough, as was the case on the Great Barrier Reef in 2016, says Tracy Ainsworth of the University of New South Wales.

Tropical corals may have disappeared by mid-century. But research published in recent weeks suggests that everything can not be lost. Christian Voolstra, a geneticist at the University of Constance, Germany, has shown that some corals can adapt to changing environments by expelling a large number of symbiotic algae and adopting a new, better-adapted set. to the new conditions. Price's findings on the massive migration of overheated tropical reef refugee coral suggest a whole new path to survival.

Until recently, subtropical regions were considered at best as marginal environments for reef-building corals, which generally require water temperatures above 64 ° F. But as the temperature increases, these waters become more and more attractive.

The critical phase of migration is during breeding, before young corals attach to reefs. Some larvae can float in the water for months. Their flyways generally follow persistent warm ocean currents that spread along the north-south coasts. This is the Gulf Stream in the North Atlantic, a similar current on the North Pacific Asian side called the Kuroshio Current and East Australian Current. Coral migrations have also been recorded along the Suez Canal, which connects the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean via the Red Sea.

There may be limits to the migration distance of tropical coral from Ecuador.

To form reefs in their new locations, young corals need a suitable bedrock bed close to the surface, where light is abundant all year round. They also need symbiotic algae to accompany them.

There may be limits to the distance at which the equator's tropical coral can migrate successfully, regardless of the sea temperature in the future. One is the amount of light that enters the reefs, especially in the winter. And the increasing acidification of ocean surface waters is an imminent threat in all latitudes, as they absorb more and more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The increase in the acidity of the seawater dissolves the skeletons of corals, composed of calcium carbonate.

But for the moment, the signs of coral migration are promising.

Price and his co-authors reviewed 92 local studies on coral recruitment in the tropics and subtropics. Most of the studies involved placing ceramic tiles on the bottom of the sea to see if new coral colonies would form on them. In total, they discovered more than 1,200 coral recruitment records, mostly in the subtropics and often less than six months after the installation of the tiles.

Japan is one of the hot spots of rebirth. Tatsukushi Bay, at the southern tip of the southern island of Shikoku, bathes in the warm waters of Kuroshio Current. At nearly 33 degrees north, it is at the same latitude as Charleston, South Carolina, and at the far end of the equator recorded by Price. The reef of Tatsukushi is not new, according to Vianney Denis, now of the National Taiwan University. But in recent decades, with the arrival of newcomers, it has become considerably denser and more diverse. More than 70 species of coral now cover 60% of the bedrock of the bay.

Staghorn coral located off Fort Lauderdale, Florida, north of their historical range, in June 2018.

Courtesy of William F. Precht

According to Yohei Nakamura of Kochi University in Tosa Bay, reef construction has been "rapidly expanding in response to rising coastal water temperatures".

Hiroya Yamano of the Tsukuba National Institute of Environmental Studies dates back to the 1930s when coral reefs were being built in Japanese waters. . With reef fish in the wake of coral, he said that "fundamental changes in … coastal ecosystems could be underway".

On the east coast of Australia, the coral of the Great Barrier Reef off Queensland is bleached and dies en masse. But refugee corals seem to migrate south to New South Wales, with reef fish living among them. Researchers reported in 2012 that four new reef-building species had appeared on the lonely islands of the state. The magnitude of the influx of tropical corals into the region remains unclear. Andrew Baird, coral reef ecologist at James Cook University and co-author of the 2012 paper, states that there is no doubt that subtropical species are increasing in abundance at the limits of their range in eastern Australia.

In Florida, the coral reefs of Staghorn and Elkhorn, which once were south of Miami, now return along the coast of the state and north of the Gulf of Mexico, say William Precht of Florida Keys and Richard Aronson National Marine Sanctuary of Sea Lab Dauphin Island, Alabama. This is despite the decline of corals in the face of diseases elsewhere in the Gulf.

The great migration of corals is part of a much larger history of marine adaptation to climate change.

History suggests that the potential for reef expansion outside the tropics in the 21st century could be considerable. At the height of the Holocene, 6,000 years ago, when the sea temperature was about 3.5 ° F warmer than today, the Coral reefs extend much further north and south than in recent times, explains Denis. The coasts of Florida and southern Japan, both of which are important in current migration, have been among those that have benefited.

According to Adriana Verges of the University of New South Wales, Australia, the great migration of corals is part of a much larger history of marine adaptation to climate change. Warm ocean currents from the tropics create hot spots that allow the spread of not only coral but also tropical fish species that graze there. It calls this a "global tropicalization" of ocean ecosystems.

Among the herbivorous travel companions are the rabbit, which has moved in large numbers to the east of the Mediterranean via the Suez Canal, as well as unicorn fish, parrot fish and surgeonfish. .

Newcomers can be voracious. Parrot fish that invade the Florida coast consume seagrasses five times faster than native grazers. And here the concerns are growing. On tropical reefs, such hungry herbivores play a valuable role in suppressing algal growth and thus helping to maintain the dominance of native coral. They can also help the recovery of corals after catastrophic events such as bleaching. But the arrival of pastures outside the tropics can destroy existing ecosystems.

Vulnerable ecosystems include kelp forests, extremely productive coastal habitats of up to tree-sized algae. According to Verges, in southern Japan invasive parrot fish and rabbit fish have eaten kelp forests on thousands of acres, thus cleaning up the seabed for coral reef construction. Japanese fishermen gave a name to the decrease in the number of kelp beds and algae: the isotake.

Should we consider such changes as the destructive invasion of alien species or the successful migration of an ecosystem threatened by climate change? There is no easy answer. As Satoshi Mitarai of the Japan University of the Okinawa Institute for Science and Technology says, a co-author of Price's paper: "The lines are really starting to fade away from what is a native species and when ecosystems are functioning or are deteriorating.

Correction of August 22, 2019: An earlier version of this article incorrectly indicated the latitude of Sydney, Australia. The city is located 30 degrees south.

[ad_2]

Source link