[ad_1]

TThe date was July 15, 1969. As the Saturn V rocket dominated the launch pad, about to send the first men to the moon, two dozen black families from the poor southern regions, accompanied by mules and mules. iconic trolleys of the civil rights movement, walked up to the Cape Kennedy fence in Florida. A flying bird, they would have looked like dwarves as a result of a colossus.

They were led by Ralph Abernathy, the successor of Martin Luther King, who had been assassinated, at the head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). He carried a sign that said squarely: "$ 12 a day to feed an astronaut. We could feed a hungry child for 8 bucks. He told a rally on the site: "We can continue from this day to Mars, Jupiter and even to heaven, but as long as racism, poverty, hunger and war prevail on Earth, we as a civilized nation, we have failed. "

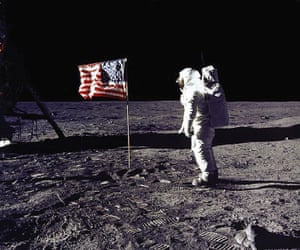

The Apollo 11 mission was hailed as the greatest technological achievement of humanity and, after the turmoil of the 1960s, a redemptive moment of national and international unity. Speaking to astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin at the lunar surface as part of what he described as "the most historic phone call ever made," President Richard Nixon said: "For an inestimable moment in the entire history of man, all the inhabitants of the Earth are truly one."

It was a myth at the time, and it will still be the case on the occasion of this month's 50th anniversary commemoration of the United States with events, exhibitions and specials. The Apollo program, motivated by the race to space against the Soviet Union, cost $ 25.4 billion, equivalent to $ 180 billion today; only the Vietnam war hit taxpayers harder. While NASA warned Congress "No money, no Buck Rogers," polls showed that a majority of Americans opposed the "coup de théâtre".

The black press asked how the price could be justified while millions of African-Americans were still mired in poverty. In his testimony before the US Senate on racial and urban poverty in 1966, King observed: "In a few years we can be sure that we are going to send a man to the moon and that with a proper telescope, he will be able to see the slums of the Earth with the intensification of congestion, degradation and turbulence ".

"Inhuman priority"

The protest march on the eve of the launch of Apollo 11 opened a new chapter in the campaign for the poor, who had built a makeshift city at the National Mall in Washington a year earlier.

Tom Paine, the administrator of NASA, went out to meet the protesters. An official NASA story recalls: "Paine was standing without a mantle under a cloudy sky, accompanied only by the NASA press officer, as Abernathy approached with his party, walking slowly and singing We Shall Overcome.

"Several mules were leading, symbols of rural poverty. Abernathy then made a short speech. He lamented the plight of the poor in the country, saying that one-fifth of the country did not have enough food, clothing, shelter and medical care. In the face of such suffering, he said that spaceflight was an inhuman priority. He urged that his funds be spent on feeding those who are hungry, clothe those who are naked, care for the sick and shelter the homeless.

Paine responded that "if we could solve the problems of poverty by not pressing the button to launch the men on the moon tomorrow, we would not press this button". He added that NASA's technical advances were "child's play" in relation to the "extremely difficult human problems" that concerned the SCLC. He offered the hope that NASA could actually help solve these problems, and then asked Abernathy, a minister, to pray for the safety of astronauts. Abernathy responded with emotion that he certainly would, and they ended this impromptu meeting by shaking hands on all sides. "

That day, among the protesters in Cape Kennedy (known as Cape Canaveral), was JT Johnson, a civil rights activist who had been with King in Memphis shortly before his death and who had become a close Abernathy collaborator. "They did not want you to be too close to the launch site, so we just picked a place and decided to hold a rally. We started talking and singing – the songs helped us through this difficult time – and we just did what we did. do, "Johnson said in an interview at his home in suburban Atlanta.

"At that time, the whole movement was focused on poverty and the poor. That's all we've talked about: how poor are we and how is this business going on the moon and spending millions when we do not have it and some people do not? have a place to live or food to eat, but we always allow all these things to happen. That was the real protest: billions for the moon and pennies for the poor. "

A project of the white America

Johnson is now an 81 year old grandfather. He is still politically active and hopes to say more about the history of the civil rights movement. Wearing a blue t-shirt in his red dining room, he remembers growing up in the days of Jim Crow's segregation in Montezuma, Georgia.

"There was a big fountain in the city center with a" colored "sign and a" white "sign while all the water came from the same place," he said. "When I was a child, I did not understand because most of these things did not seem right to me. So, the Lord knew that I was going to be in the movement before me, because I did not know it and some of the things I just did not like. It was not fair.

As for many, King became his hostess. "When I met Dr. King, I thought he was the man I was waiting to see all my life and I dedicated myself to the civil rights movement."

In a protest in the 1960s, Johnson and others jumped into a white pool in St Augustine, Florida, only to have the hotel owner pour acid into the swimming pool. After trying to integrate another pool in Albany, Georgia, he was jailed for six days and went on a hunger strike. In this context, President John F. Kennedy's dream of placing a man on the moon by the end of the decade seemed a luxury that America could not afford.

"I think everything was a matter of public relations for the United States and Russia," he said. "I think this country has never really cared for people here … African Americans have never had their share; they spread it around everyone. "

Indeed, the Apollo program gave the impression of being a project of the White America. While the images of the time are rebroadcast on the occasion of the half-centenary, it is striking that the 12 people who walked on the Moon were white men, as well as the l? overwhelming majority of civil servants, engineers and scientists in charge of mission control. Whitey on the moon, musician and poet Gil Scott-Heron, sums it up in these terms: "A rat bit my sister Nell / With Whitey on the moon / Her face and her arms began to swell / And Whitey on the moon."

Johnson said, "We have not heard any invitation. we did not have anything. So we thought it was a shame and a disrespect for us all … It was white people who were privileged in this country and they did it for themselves. "

"A proud American"

Johnson did not linger at Cape Kennedy to witness the epic launch of the Saturn V rocket. But like millions of people fascinated around the world, he watched on television when Armstrong stepped on the surface lunar. He recalled: "I imagine it was exciting to see this happen, to be very forthright with you, but the next day we came back to the same thing. How can we feed our hunger? "

Others, however, felt differently. Abernathy stayed to watch the launch in person. University professor and professor of mathematics, he was not opposed to Apollo, but "in the distorted sense of national priorities of the country."

Her 11-year-old daughter, Donzaleigh, said over the phone: "He wanted to draw attention to the fact that we are spending billions to send men to the moon, but we can not feed them. hungry children. America. In doing so, my father also drew the attention of members of Congress to the problem of hunger and poverty.

"It was finally a win-win situation: my father said that he felt like a very proud American and that just when this rocket was launched into space, it was not hunger but from poverty it was an accomplishment of human beings. And it's miraculous in itself.

Donzaleigh, an actor who played alongside Meghan, the Duchess of Sussex in the drama Suits, shares her father's ultimately positive view of space exploration. "I do not think it would be right or right to say no … I think it would be against the good of humanity.

"However, you can not do this singularly and not look back at those in front of your face every day who are dying of starvation, wallowing in poverty."

The "fallout" of NASA

Donzaleigh recalled that Abernathy had a major impact on NASA scientists, urging them to use technology to deal with urgent domestic needs such as air and water pollution. "Scientists have the ability to positively influence our world, they have done it and I am so happy that scientists have listened to it," she said.

According to Neil Maher, associate professor at the New Jersey Institute of Technology and Rutgers University, although NASA has never publicly stated that Abernathy's protest is putting pressure on her to tackle Afro's poverty. -Americans, she began to take steps to remedy these problems soon after.

"In 1972, the space agency created a project office on urban systems at Johnson Space Center in Houston, which redeveloped the technologies deployed for Apollo for use in US city centers," said an email to Maher, author of the book Apollo in the Age of Aquarius. "These" spin-offs "included water filtration systems, air pollution monitoring technologies, and even energy-efficient Apollo space capsule heating and cooling systems for use in projects. low income housing.

"Although these efforts have had the best intentions in the world, many of these technologies have unfortunately failed to dramatically improve the daily lives of African Americans living in American cities."

After Armstrong's giant leap for mankind, the novelty quickly disappeared, public interest in landings on the moon faded and doubts about its cost intensified. Nixon shortened the Apollo program and rejected a proposal to build a lunar base. Since then, NASA's workforce, including astronauts, has grown considerably and America has elected its first black president. But the nation that put a man on the moon has still not solved racism, inequality, or poverty.

For Johnson, who had been at the SCLC for 17 years and then set up a political consulting firm, there is a sense of disappointment and waste of opportunity. He avoids going to downtown Atlanta, where people sleep under bridges: "It makes me feel sick." For his part, he will not celebrate the golden anniversary of this transcendent moment on his most close neighbor.

"This country is always the same, people are always poor, they are always hungry and this has not been corrected," he said. "So we always play the same game and no one really protests.

"What I want to see is the end of poverty, people who are not hungry, people who have a home and can enjoy life. We invest our money in science to get rid of Alzheimer's disease, MS and all those different things that paralyze us. We can live very happily in our own clothes and, as my grandmother said, in our own spirit, until our death. That's how I would like to see this Earth. "

[ad_2]

Source link