[ad_1]

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to have unusual and unexpected effects on a number of respiratory illnesses – some have been canceled, others have passed through and even more are rebounding out of season. These flows complicate medical responses to the pandemic, but also offer scientists the opportunity to study how these viruses spread.

As cold and flu season ostensibly begins in the northern hemisphere, researchers warn to expect the unexpected. “If someone tells you they know, they don’t know,” says epidemiologist John Paget of the Dutch Institute for Health Services Research in Utrecht. Most agree that the flu will eventually rebound, perhaps violently, as travel restrictions and societal interventions designed to curb the coronavirus, such as wearing masks, diminish. “Once we let go of our good health practices, the flu is likely to hit hard,” says Robert Ware, clinical epidemiologist at Griffith University in Queensland, Australia.

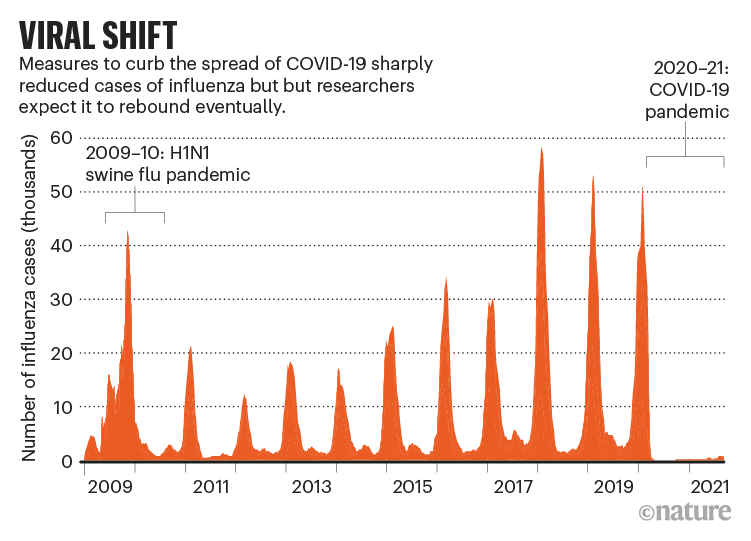

Seasonal flu typically kills between 290,000 and 650,000 people per year worldwide. But for most of 2020 and 2021, it has all but disappeared from much of the globe. FluNet, a global influenza virological data tracker maintained by the World Health Organization, shows that the proportion of positive influenza tests has remained roughly stable since April 2020, despite increased surveillance (see ” Viral transfer ”).

Flu break

The United States recorded just 646 flu deaths in the 2020-21 season – the annual average is in the tens of thousands; there has been only one death from pediatric influenza. Australia has not recorded any deaths from seasonal flu so far in 2021, compared to 100 to 1,200 in previous years.

The decline in influenza has persisted despite the variable lifting of social interventions to curb the coronavirus. This highlights the importance of international travel in bringing the flu to a particular country, says Richard Webby of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee. “That says a lot about seeding events and how important they are,” he says. The flu has continued to circulate at low levels in the tropics, the researchers note, and will therefore likely spread from there once borders reopen.

Pandemic response measures also appear to have suppressed some bacterial infections, including those that cause pneumonia and meningitis and are associated with sepsis.1. But some viruses behaved differently. Rhinoviruses, for example, a major cause of the common cold, have continued to spread throughout the pandemic, and infections have even increased in some countries2, perhaps because these viruses are not as sensitive as many others to measures such as cleaning surfaces and washing hands, and because they face little competition from other respiratory viruses. There is new evidence that these mild viruses could protect people from more serious illnesses during infection.3,4.

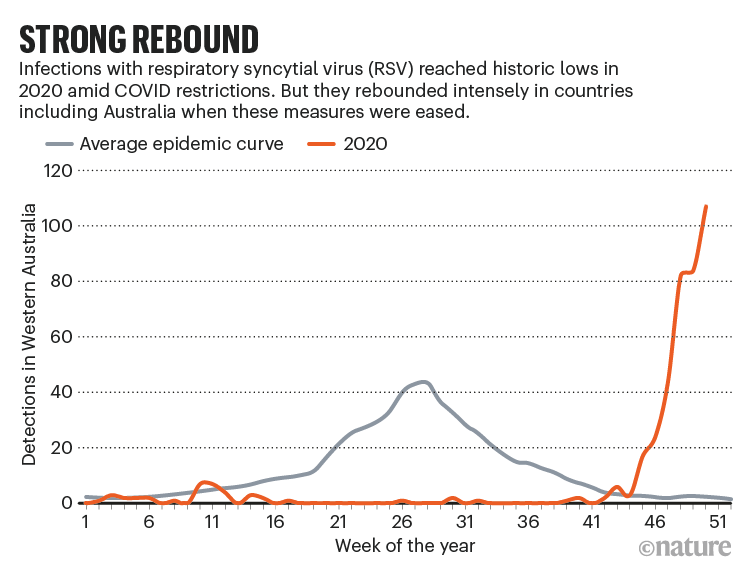

And some typical winter viruses have rebounded out of season. Infections from common human coronaviruses (another big culprit of the common cold) and parainfluenza viruses were at very low levels in the United States in 2020, but started to reach pre-pandemic levels in the spring of 2021 – an unusual time for colds. Likewise, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infections, which typically cause mild symptoms of the common cold but are also responsible for around 5% of deaths of children under 5 globally, are at an all-time high. low for a year, then started to increase months later than usual, in April 2021. RSV infections continued to increase in late August (see “Strong rebound”).

Peaks out of season

The oddly timed bumps could be linked to the reopening of schools, according to a report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC).5, as well as an accumulation of susceptible and unexposed infants in the absence of vaccine (vaccines against RSV are under development).

Out-of-season RSV peaks have also been seen elsewhere, in countries such as South Africa, Japan, Australia and the Netherlands. In Western Australia, a peak in RSV in December 2020 was 2.5 times greater than the peak in July for 20196. However, a sudden onset of the disease does not necessarily translate into a higher number of cases overall: the total number of RSV cases in Queensland was below normal, Ware notes, “but because all cases got closer, it was much more intense “, putting pressure on health resources (see third figure).

It would be concerning to see rebound effects caused by a build-up of immunologically naive people in seasonal flu, the researchers warn. All over the world, there are signs of the H3N2, H1N1 and B influenza viruses circulating, says Amber Winn, an epidemiologist with the CDC’s viral disease division in Atlanta, Georgia. A wave of influenza B infections during the winter of 2019-2020, she notes, has contributed to a record number of pediatric influenza deaths this season. “That’s why it can be especially important to get the flu shot this season,” she says.

[ad_2]

Source link