[ad_1]

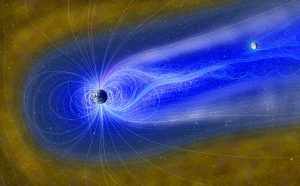

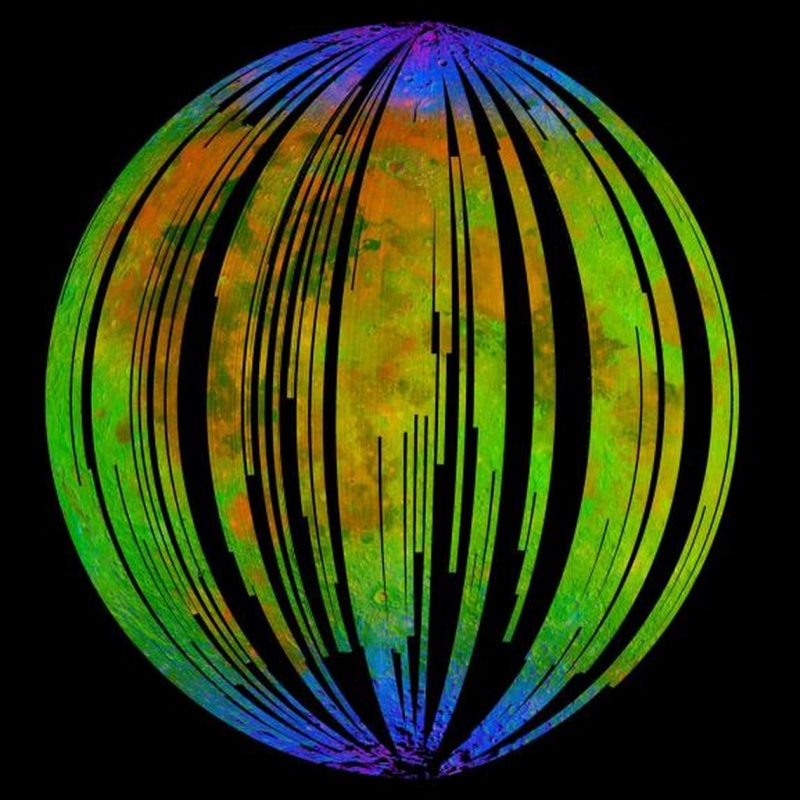

Artist’s concept of the moon in the Earth’s magnetic tail, the part of our magnetosphere that extends outward from our sun. The moon sweeps this tail every month on a full moon. Image via E. Masongsong / UCLA / EPSS / NASA / GSFC / SVS / Duluth News Tribune.

By Bob King, aka AstroBob. Originally published in the Duluth News Tribune on February 16, 2021. Reproduced here with permission.

Finding water on the barren moon is one of the most remarkable discoveries of the post-Apollo era. Satellite mapping has revealed ice in permanently shaded craters at the lunar poles and more recently at Clavius, a prominent crater on the near lunar side that basks in the sun two weeks a month. Comets and meteoroids likely delivered the water that eventually froze to ice, although water-rich lava that erupted in the moon’s distant past may also have contributed.

EarthSky’s lunar calendar shows the phase of the moon for each day this year. Order yours before they go!

The orange ground stumbled by the Apollo 17 astronauts contained droplets of glass sprayed by a fountain of volcanic fire 3.64 billion years ago. Subsequent scans found water trapped inside some of the beads. Image via NASA / Duluth News Tribune.

Back on Earth, scientists found water trapped in volcanic glasses and rocks collected by the Apollo 15 and 17 astronauts. In 2019, NASA’s LADEE (Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer) mission discovered that the constant flow of micrometeorites (tiny space rocks) bombarding the moon creates a thin and temporary atmosphere of water vapor. When the particles penetrate at least 3 inches (8 cm) into the surface, the shock of the impact releases water molecules attached to the minerals in deeper soil not exposed to direct sunlight.

Just to be clear, the moon is far from drenched, but it’s not the dry place we once thought. By comparison, the drier expanse of the Sahara Desert contains 100 times more wet matter than the moon. To fill your 16-ounce water bottle, you’ll need to process about one metric ton of lunar soil.

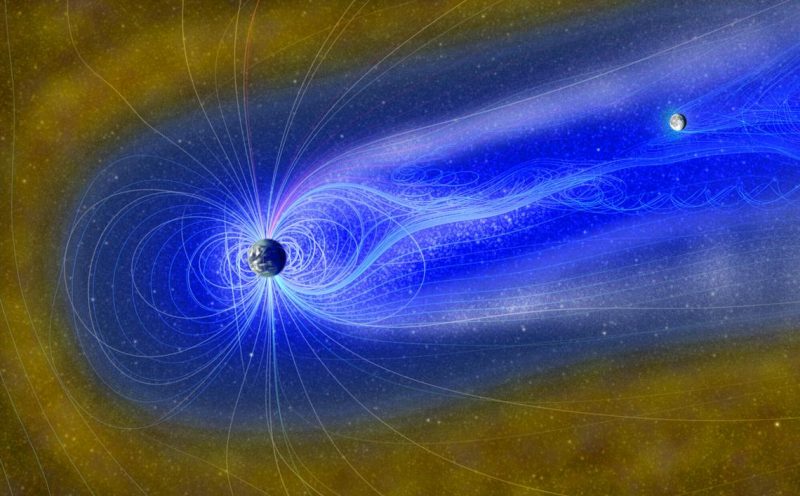

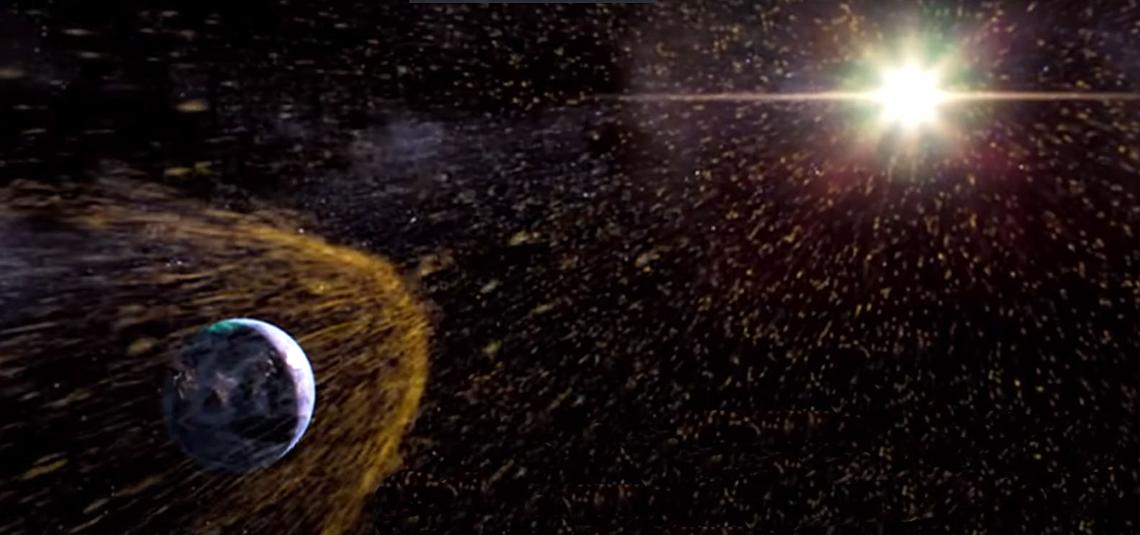

The flow of protons and electrons expelled by the sun called the solar wind affects the Earth (shown here) and the moon. Protons (hydrogen) in the wind bind with oxygen in the lunar soil to produce water. Image via NASA / Duluth News Tribune.

The sun also helps distill water drops and specks from the moon when protons from the solar wind crash into the lunar surface and bind with oxygen atoms in the minerals to form H2O. Protons are basically hydrogen atoms that have lost an electron. These are the “H’s” in H2O. By the way, the same solar wind sometimes binds to the Earth’s magnetic field and delivers hordes of protons and electrons that set off the Northern Lights.

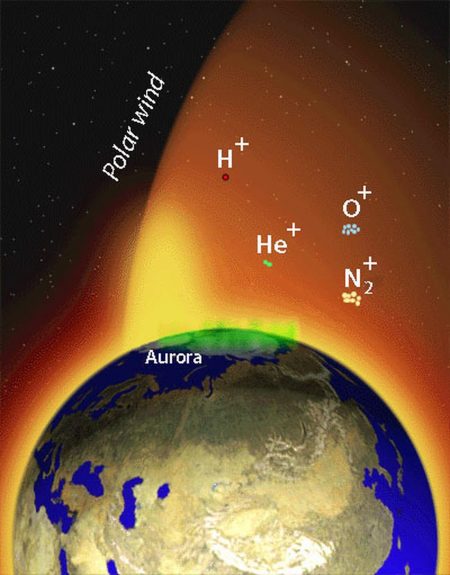

In a new study, a team of scientists has found that a “land wind” of ionized atoms blowing from polar regions can interact with lunar soil and rocks to form water molecules. H represents hydrogen; He for helium, O for oxygen and N2 for nitrogen. The plus sign means that the atoms or molecules have lost an electron and are positively charged. Image via NASA / Bob King / Duluth News Tribune.

A study published on February 1, 2021 in the Letters from the Astrophysical Journal discovered that Earth could also play a key role in creating water. Similar to the wind of electrified particles from the sun, Earth has its own wind made up of ionized hydrogen, helium, oxygen, and nitrogen. “Ionized” means that atoms have lost an electron and carry a positive charge.

Energized by interactions with the solar wind, some of the ionized atoms and molecules in the planet’s polar atmosphere propagate into space where they are trapped by the Earth’s magnetic field, better known as the magnetosphere.

Most of the time, the moon moves away from the magnetosphere, which moves away from the sun like a weather vane, but for 3 to 5 days per month, it crosses it at the time of the full moon. The magnetosphere deflects the solar wind, preventing protons from the sun from churning fresh water onto the lunar surface. With the moon cut off from its supply, astronomers speculated that the lunar water formed by solar bombardment would quickly disappear into space, and the moon would emerge from its temporary magnetic shelter all the drier.

This image of the moon is from NASA’s Moon Mineralogy Mapper on the Indian probe Chandrayaan-1. Small amounts of water and hydroxyl (bound to water) are shown in blue. Most of the moon’s water is concentrated in the colder polar regions. Image via ISRO / NASA / JPL-Caltech / Brown University / USGS.

But no! Using data from the Indian Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft, which mapped water in the moon’s polar regions, Chinese researchers have made a startling discovery. The water levels have stayed almost the same each time the moon exits the magnetosphere. Something had to project protons on our satellite to keep the water coming. The polar wind from Earth seemed the likely suspect.

Further evidence came from the Japanese lunar orbiter Kaguya, active in the early 2000s, which detected piles of positively charged oxygen atoms on the moon whenever it hid in the shadow of the magnetic tail of the Earth. In addition to hydrogen, oxygen can also help create water on the moon. How amazing it is to think that ionic breezes from Earth can help cover the lunar surface with vital water potentially beneficial to future astronauts.

Bottom line: Particles transported from the Earth’s poles via our planet’s magnetosphere could interact with moon rocks to create small amounts of water on the moon.

Source: Earth wind as a possible exogenous source of hydration of the lunar surface

Via Duluth News Tribune

[ad_2]

Source link