[ad_1]

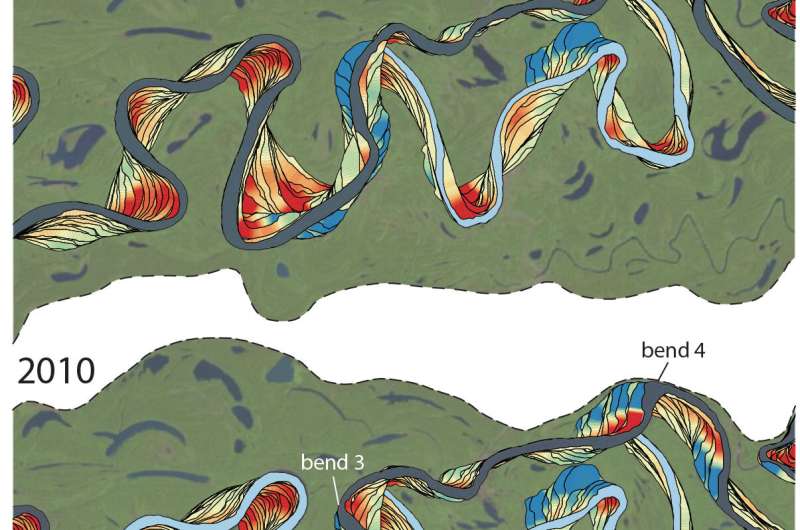

Satellite images of the Mamoré River colored to illustrate changes in flow path and sediment deposition in the form of dot bars (red) and counterpoint bars (blue). From 2005 to 2010, the river (dark blue) suffered a neck cut (light blue). This change in flow path results in the formation of small, very curved elbows (elbows 1 and 2). Counterpoint bars form behind elbow 2 as it migrates downstream. Credit: Sylvester et al.

It is not uncommon for crescent-shaped strips of sand to dot the banks of meandering rivers. These swaths typically appear along the interior side of a river bend, where the bank wraps around the sandy area, forming deposits known as “point bars”.

When they appear along an outer bank, which curves in the opposite direction, they form “counterpoint” bars, which are generally interpreted by geoscientists as an anomaly: a sign that something – like a patch. of erosion-resistant rocks – interferes with the usual mode of sediment deposition of the river.

But according to research by the University of Texas at Austin, counterpoint bars aren’t the quirks they’re often meant to be. In fact, they are a perfectly normal part of the meandering process.

“You don’t need a strong substrate, you can become beautiful [counter-point] bars without it, ”said Zoltán Sylvester, a researcher at UT’s Bureau of Economic Geology who led the study.

The finding suggests that counterpoint bars – and the unique geology and ecology associated with them – are more common than previously thought. Awareness around this fact can help geoscientists to be on the lookout for counterpoint bars in geological formations deposited by rivers in the past, and to understand how they can influence the flow of oil and water. that cross them.

The research was published in the Bulletin of the Geological Society of America March 12.

The co-authors are David Mohrig, professor at the UT Jackson School of Geosciences; Paul Durkin, professor at the University of Manitoba; and Stephen Hubbard, professor at the University of Calgary.

Rivers are constantly in motion. For meandering rivers, that means blazing new paths and reactivating old ones as they meander through a landscape over time.

The researchers observed this behavior both in an idealized computer model and in nature, using satellite photos of a stretch of the Mamore River in Bolivia, known to change course rapidly. Satellite photos showed how the river changed in 32 years, from 1986 to 2018.

In the model and the Mamoré, counterpoint bars appeared. The researchers found that the appearance was directly related to short, sharp turns: small spikes in the path of a river.

Researchers observed that these spikes form frequently when the course of the river is suddenly changed, such as when a new oxbow lake forms through a cutoff, or after reconnecting to an old oxbow lake.

But tight turns don’t stay put, they start to migrate downstream. And since they move quickly downstream, they create the conditions for sediment to collect around the turn as a counterpoint bar.

The study shows a number of examples of what is happening in the Mamoré. For example, in 2010, a sharp turn (turn 2 in the image) is formed when an ox lake reconnects to a part downstream of the river. In 2018, the bend moved about 1.5 miles downstream, with counterpoint deposits along the shoreline marking its path.

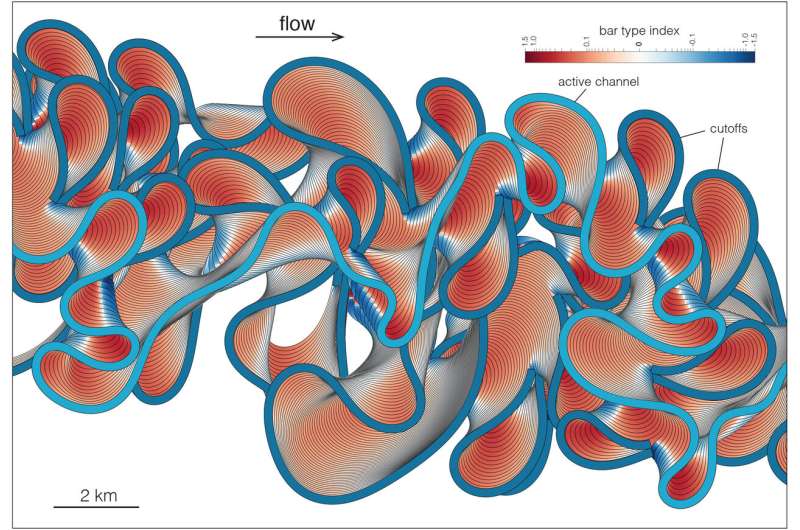

Geomorphologists and engineers have known for some time that long-term changes along a river can be described in terms of local and upstream curvature values (places where the river appears to wrap around a small circle have high curvatures). In the study, the researchers used a formula that uses these curvature values to determine the likelihood of a counterpoint bar forming at a particular location.

A computer generated graphic of a meandering river and associated sediment deposits. The lighter blue represents the current flow of the river. Darker blue represents old flow areas that were cut off due to the meanders of the river. The striated regions along the flow paths represent sediment deposits as dotted bars (red) and counterpoint bars (blue). Credit: Sylvester et al.

Sylvester said he was surprised at how well this formula – and the simplified models used in part to derive it – worked to explain what was thought to be a complex phenomenon.

“Natural rivers, they’re actually not that far from what these really simple models predict,” Sylvester said.

This isn’t the first time Sylvester’s research has revealed that the behavior of rivers can be governed by relatively simple rules. In 2019, he led a study published in Geology that described a direct relationship between sharpness of turns and river migration.

Superficially, point bars and counterpoint bars resemble each other and frequently blend into each other. But counterpoint bars are distinct environments: compared to point bars, they have finer sediment and lower topography, making them more prone to flooding and lake reception. These characteristics create unique ecological niches along rivers. But they are also geologically significant, with ancient deposits of counterpoint bars preserved underground that influence the flow of fluids, such as water, oil, and gas.

Mathieu Lapôtre, a geoscientist and assistant professor at Stanford University, said recognizing that counterpoint bars can easily form in meanders of rivers – and having a formula to predict where they will form – is a significant advance .

“Overall, the results of Sylvester et al. Have important implications for a range of scientific and technical issues, ”he said.

Steep turns make rivers wander

Bulletin of the Geological Society of America, DOI: 10.1130 / B35829.1 / 595343, pubs.geoscienceworld.org/gsa/g… nd-counter-point-bar

Provided by the University of Texas at Austin

Quote: Winding rivers create “ counterpoint bars ” regardless of underlying geology (2021, March 16) retrieved March 16, 2021 from https://phys.org/news/2021-03-meandering -rivers-counter-point-bars-underlying .html

This document is subject to copyright. Other than fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.

[ad_2]

Source link