[ad_1]

Watch the CBS News prime-time special "Man on the Moon," celebrating the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11, Tuesday at 10 / 9c.

Less than two weeks before Apollo 11's historic launch to the moon 50 years ago, flight controllers and stand-in astronauts carried out a final simulation of the plan descent to the lunar surface. Though few knew it at the time, that would have ended up playing a key role in the history-making moments the world would soon follow on live TV.

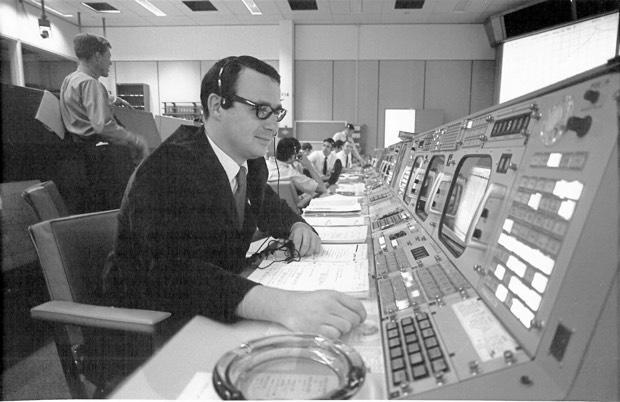

Three minutes after the computers running the simulation began the fate of the world, the 26-year-old Steve Bales, the warnings of a computer alarm code – 1201 – flash on his monitor. He had never seen what he meant.

Apollo 11: Celebrating 50 years

more

More in Apollo 11: Celebrating 50 years

Neither did the two astronauts standing in command Neil Armstrong and lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin.

Quickly referring to a software manual for the lander's guidance computer, Bales saw the 1201 alarm indicated "executive overflow" and "no vacant areas." Clearly, something was overloading the computer, preventing it from completing its computations in a given cycle. But what was not getting done? And was it mission critical?

In his book "Failure Is Not An Option," Apollo 11 descent flight director Gene Kranz described the critical moments that followed. After more alarms popped up in quick succession, Bales called Jack Garman, has a 24-year-old lunar module software expert in a nearby support room.

"Jack, what's the hell going on with those program alarms? Do you see anything wrong?" Kranz recalls Bales asking. Garman replied, "It's a bailout alarm." "The computer is busier than hell for some reason, it's gotten out of time to get all the work done."

Meanwhile, the lunar module was continuing its imaginary descent, and its systems seemed to be operating normally. But something was clearly wrong, and there were no rules defining a procedure to correct the problem. After still more alarms, Bales, seated on the right of a group of consoles known as "The Trench," reached a decision.

"Flight, Guidance," he called over his headset to Kranz. "Abort the landing … ABORT!"

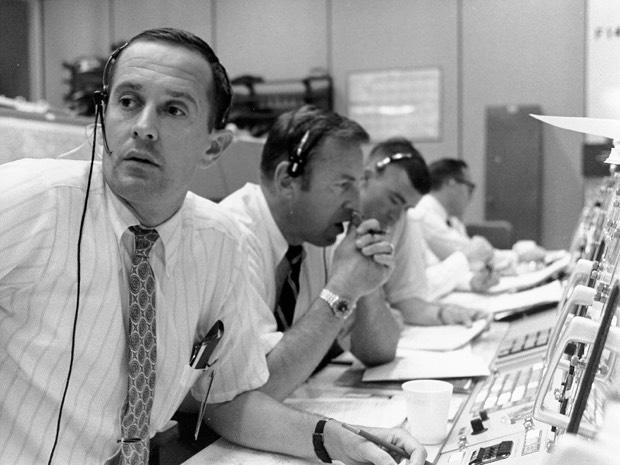

Astronaut Charlie Duke, the capsule communicator, or CAPCOM, responsible for relaying comments and instructions to the crew, turned to Kranz and asked, "We're going to call an abort, Flight?" Kranz sharply replied, "Abort, CAPCOM, abort." Duke relayed the instructions and the crew executed an abort, carrying the steps needed to jettison the descent stage and return to orbit.

The simulated abort came just 11 days before.

Kranz was not happy. He wanted to end up the final simulation with a successful landing, an upbeat rating leading to NASA's ultimate flight. "Dammit, we should have finished our training with a landing on the surface," he wrote.

But it turned out, the aborted landing was a godsend. Richard Koos, the simulation supervisor who added the computer alarms to the final test run, said the alarms in question were not mission critical.

In fact, the lunar module was operating smoothly and only lower-priority items were triggering the alarms. Continuing with the descent was a much safer option than a low-altitude abort.

Bales, now 76 and long retired from NASA, recalls the simulation like it was yesterday.

"After the sim, we're unplugged, Gene said," Bales said in a recent interview with CBS News from his home near Philadelphia. "He said, I want you to go and add these (computer alarms) to your rules." I said "Gene, I've got a gazillion things to do." things, and he said I do not care what you say, get it done. "

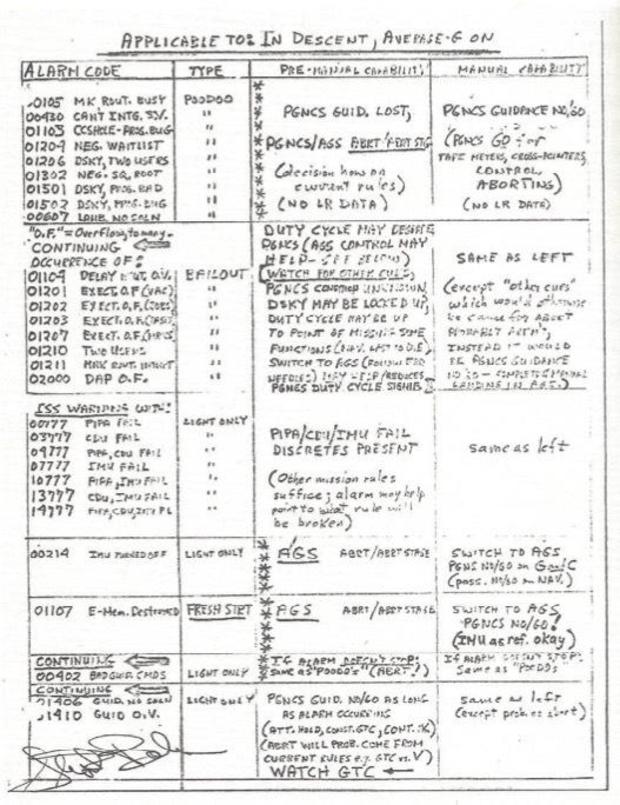

Bales called Garman and asked him to consult with the MIT engineers who developed the lunar module's software and came up with a "cheat sheet" defining what was needed in response to various alarm codes.

"The MIT guys will probably tell you, but who cares?" Bales said. "I did not want somebody who could do it, I wanted to get somebody like Jack, who was one of the smartest guys I ever put, looking at what somebody else had done and how you should work."

A week later, Garman presented a list of codes and responses, written by hand on a single sheet of paper. Bales taped a copy of his mission in the mission control center. He did not think it would ever be needed.

"There was not much that we could do anything about," he said. "Some of them, if they came up the computer was gonna stop." "You're done." – 1210, 1201, 1202, maybe one or two others – you had to make a choice. and off we went. "

Tensions high as Apollo 11 gets underway

Apollo 11 finally got underway at 9:32 AM EDT on July 16, 1969.

Strapped into the Apollo command module Columbia atop their huge Saturn 5 rocket, mission commander Neil Armstrong, lunar pilot module Buzz Aldrin and command module Mike Collins pilot shot smoothly into Earth orbit.

NASA's Manned Spacecraft Center (now the Johnson Space Center) in Houston, United States.

Three days later, at 1:21 pm on Saturday, July 19, the astronauts braked into orbit around the moon. The next day, Armstrong and Aldrin bid farewell Collins, entered the lunar lander Eagle and the crew of the 13th lunar orbit.

Coming into the work of the morning of the morning. "You could cut that with a knife," he said.

Armstrong and Aldrin began the descent towards a target altitude of 50,000 feet above the lunar surface. At that point, the crew would fire the lunar module's main engine – powered descent initiation, or PDI – to begin the 12-minute plunge to the targeted landing zone in the Sea of Tranquility.

During that final pass behind the moon, with the control of a final flight. Kranz gave an impromptu, now legendary speech on an unrecorded audio channel only accessible to his White Team flight controllers.

"I remember this so clearly," Bales recalled. "He said we're walking out of this room, we're going out a team, we're going out, we're going out the leader says I'm with you, and it's my responsibility whatever you guys do, that was incredible … I remember that clearer than the landing. "

The eagle swung back to contact with the earth and the next 13 minutes – the time it would take to the distance to reach 50,000 feet where powered up velocity and velocity and general health. And right away, there were problems.

"So we come around the hill, we do not know anything's going wrong at all, neither does the crew," Bales said. "And then the comm [communication] is so bad, if you listen to that com you'd wonder we're going to be able to go on or not. Gene is having to figure out he is going to allow us to go on. That was his call … and boy, it was dicey. "

As it turns out, a shield has been added to the thrust of a maneuvering thruster was partially blocking the radio signal. Don Puddy, a flight controller monitoring communications, asked the crew to turn the lander slightly "and comm cam back," Bales said. "So Gene says, you're going for the descent, everything's looking great."

But voice communications and telemetry were still intermittent, and we have no telemetry data, we have no voice data, we just have a bunch of noise , "Bales said.

"I'm sitting there praying"

Two minutes later, telemetry resumed and Bales quickly saw a guidance issue. The lander was descending to the moon 20 feet per second faster than it should have been. That mismatch could have been due to an external force that had not been taken into account; it could have had a problem with the inertial guidance system; it could have been a problem with the spacecraft's accelerometers.

The powered descent phase of the flight was designed to be an important part of the journey to the surface – but only if the rate was within 35 feet per second of the planned velocity. Eagle was more than halfway to that limit.

"So I'm sitting there praying," Bales said. "I said oh, this thing got to hold (steady) If it holds, we're OK If you listen to the tapes, somewhere I say, Gene, that's downrange, we're going to make it, I think. You are not supposed to say 'I think,' but I think it's a good idea, but it's been held constant, it's held and held and held. "

Bales began to relax a bit. Aboard Eagle, Armstrong and Aldrin, who had been facing the surface to track landmarks, yawed the lander to help his radar lock onto the ground.

"And we said this is great, because you could see that radar said hey … we're off about 3,000 feet in altitude and we're off exactly what we saw, 20 feet per second in altitude rate," Bales said . Using the radar data, the computer could correct for the higher-than-expected rate of descent. And it did just that.

The lander would still be missed, but it would have been a good idea it could not fix the downrange. "

In other words, so far, so good.

Around this time – just over seven minutes to touchdown – Aldrin entered the computer to calculate the difference between the radar readings and the computer's predicted altitude. That was necessary to give the crew situational awareness in case of problems that prevented communications with mission control.

Aldrin entered the command "and wham, he says we just got an alarm, 1202," Bales said. It takes telemetry a few seconds to reach Earth, get processed and displayed in mission control, "I think it's about a three-to-two delay before we even see it."

Bales and Garman immediately thought of the July 5 landing simulation. So did Kranz and Duke. Armstrong and Aldrin did not participate in the simulation and were never briefed on the program or what could cause them.

The 1202 alarm "tells us the computer is behind in its work," Kranz wrote. "If the alarms continue, the guidance, navigation and crew display will become unreliable. doubt and distraction, two of a pilot's deadliest enemies. "

A few seconds went by. Suddenly, Armstrong comes on the audio loop and ratchets up the voltage, saying "give us a reading on that 1202 program alarm." His tone of voice left no doubt he expected a quick response.

"I am frantically … trying to remember where my little cue is Jack, thank God, Jack is saying Steve, Steve, we're GO unless it keeps reoccurring … I said Jack, I trust you. I say, Flight, we're going on the alarm, it was an eternity in the control room.

It was more like 31 seconds, and in the world of flight operations, that would be as close to eternity as any controller would ever want to get. Charlie Duke knows that as well as Bales.

"When Neil says 'give us a reading,' Charlie knew he'd better do something quick," Bales said. "And so the only time in the descent, the only time ever I heard him do so, I said we're GO and he did not even wait for Gene.If you listen to the loops, he's telling the crew before Gene even it's OK and that's usually a no-no.

"But if it had not done that, I think we would not have made it, I think the crew would have bailed out." I really do. he saved it right then and there. "

But it was Bales' responsibility. Kranz, Duke or even Garman, who is always ready for the guidance of the world.

As the MIT computer experts would later explain, the guidance computer is running at about 83 percent capacity during that phase of mission operations. Another 13 to 14 percent was lost to interference from a communications circuit between the computer and the lander's radar rendezvous. When Aldrin asked the computer to display the altitude data, "it was just enough to trip it over," Bales said. "And for at least one second, it does not get everything done. That's where you get the 1202."

The descent continued. Aldrin has been told to add to the data and to rely on additional missions. Program, but they did not occur so close that they violated the subjective definition of "recurring." Bales and Garman were "GO" almost as soon as each alarm was called out.

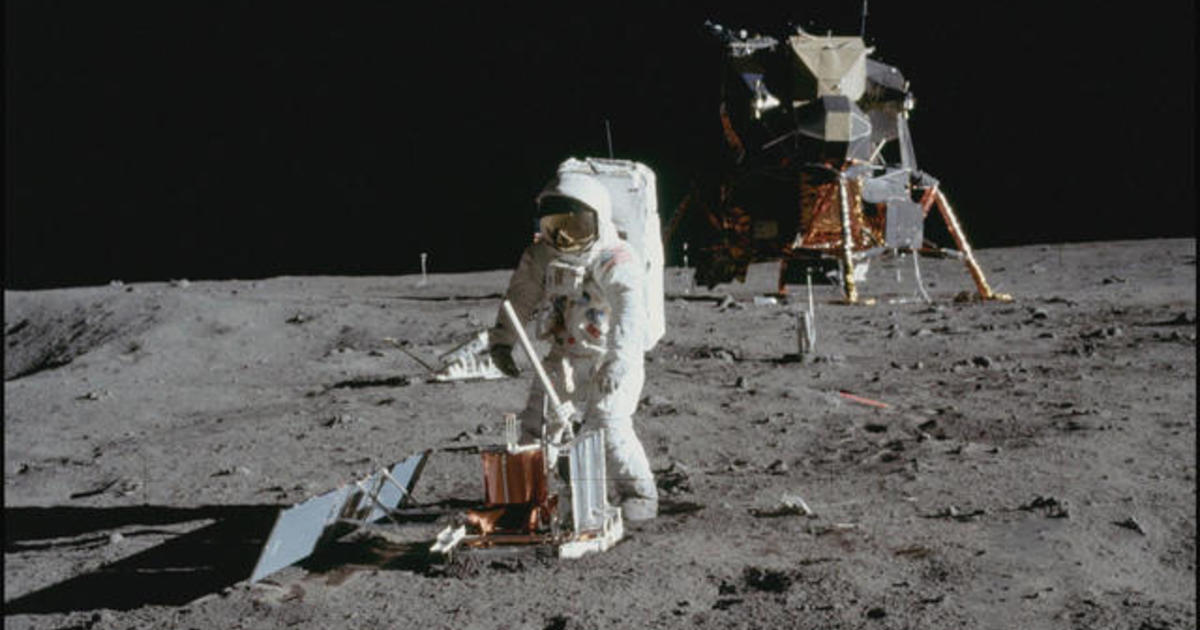

Because of the downrange error noted during the initial descent, Eagle was taking the crew to a boulder-strewn crater. Armstrong took over manual control. He halted the descent, hovered and then flew sideways in search of a smoother landing area. Nervous flight controllers Aldrin called down altitude, vertical and horizontal velocity in feet per second.

As if the drama could get more intense, sloshing propellant uncovered a low-level fuel sensor indicating the tank would run dry in 60 seconds. And the lander was still well above the surface.

"Sixty seconds," Duke called out.

Busy flying the lander, Armstrong did not reply. Aldrin continues his running commentary, saying: "Lights on. Down 2 1/2 (feet per second) .Forward, forward, good, 40 feet (up), down 2 1/2." Kicking up some dust. 1/2 down Faint shadow 4 forward 4 forward Drifting to the right a little OK Down a half.

Duke sends up another fuel warning: "Thirty seconds …"

And then, just in the nick of time, Armstrong set the lander down and shut off its engine.

"We copy you down, Eagle," Duke called.

"Houston, Tranquility Base, The Eagle has landed," Armstrong famously replied.

Armstrong stepped onto the moon's surface six hours and 39 minutes after landing, taking a "giant leap for mankind." Aldrin followed a few minutes later, and was collecting 48 pounds of rocks and soil, deploying scientific instruments, erecting a U.S. flag and taking a congratulatory phone call from President Richard Nixon.

Twenty-one hours and 36 minutes after landing, the two men blasted off and headed back to lunar orbit where they docked with the command module Columbia for the trip home. They landed with a Pacific Ocean splashdown on July 24.

Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins later on the Medal of Freedom from President Nixon, the highest honor of the United States civil awards. Nixon also gave the mission operations team to the NASA group achievement award. Steve Bales, Steve Bales.

He would go on to serve as deputy director of mission operations at the Johnson Space Center before retiring to pursue business interests in the chemical industry.

Bales said, "I'm not sure 50 years later, I really do not know it, it's really a boost for the country when it's really, really needed it. (Purpose) I do not know, I can not know how to do it!

"But when we finally do, it's going to be something that's incredible."

Editor's note: Portions of this story originally appeared in Astronomy Now magazine.

[ad_2]

Source link