[ad_1]

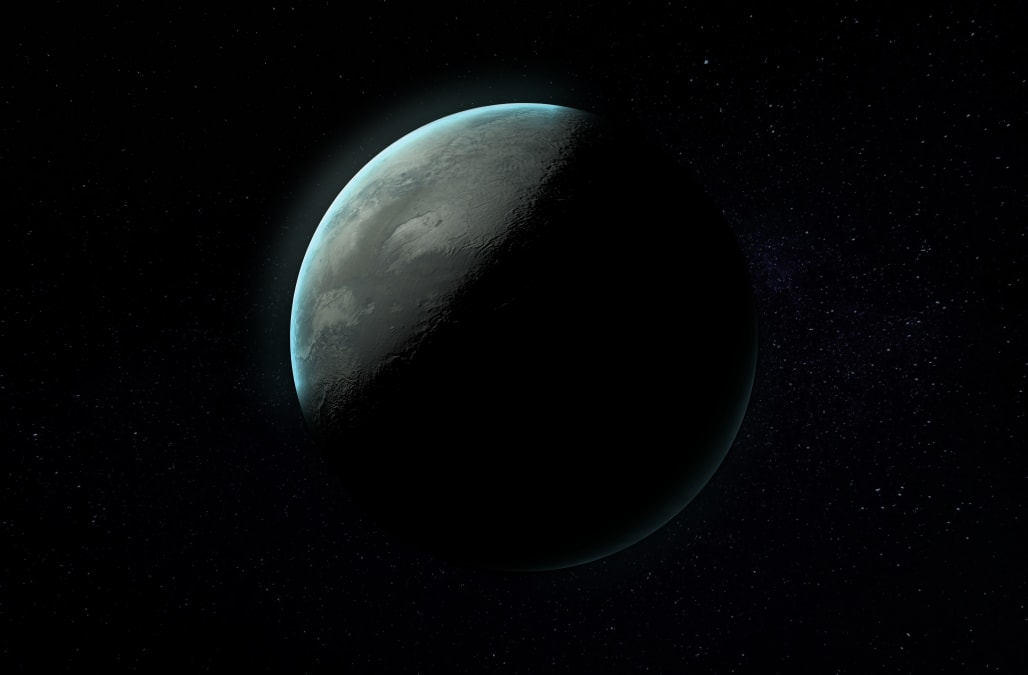

The nearest single star to the sun apparently hosts a big, icy planet.

Astronomers have found strong evidence of a frigid alien world about 3.2 times more mbadive than Earth circling Barnard’s Star, a dim red dwarf that lies just 6 light-years from the sun. Barnard’s Star is our sun’s nearest neighbor, apart from the three-star Alpha Centauri system, which is about 4.3 light-years away.

The newly detected world, known as Barnard’s Star b, remains a planet candidate for now. But the researchers who spotted it are confident the alien planet will eventually be confirmed. [Barnard’s Star b: What We Know About the “Super-Earth’ Candidate]

“After a very careful badysis, we are 99 percent confident that the planet is there,” Ignasi Ribas, of the Institute of Space Studies of Catalonia and the Institute of Space Sciences in Spain, said in a statement.

“However, we’ll continue to observe this fast-moving star to exclude possible, but improbable, natural variations of the stellar brightness which could masquerade as a planet,” added Ribas, the lead author of a new study announcing the detection of Barnard’s Star b. That study was published online today (Nov. 14) in the journal Nature.

Barnard’s Star b, if confirmed, will not be the nearest exoplanet to Earth. That designation is held by the roughly Earth-size world Proxima b, which orbits Proxima Centauri, one of the Alpha Centauri trio.

NASA’s Kepler space telescope showed that small planets are common in the Milky Way galaxy at large. Together, Proxima b and Barnard’s Star b strongly suggest that such worlds “are also common in our neighborhood,” study co-author Johanna Teske, of the Department of Terrestrial Magnetism at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, D.C., told Space.com. “And that is super-exciting.”

A near solar neighbor

Barnard’s Star is named after the American astronomer E.E. Barnard, who in 1916 discovered the speediness Ribas mentioned. No other star moves faster across Earth’s sky than Barnard’s Star, which travels about the width of the full moon every 180 years. [Gallery: The Strangest Alien Planets]

This unparalleled apparent motion is a consequence of the proximity of Barnard’s Star and its high (but not record-setting) velocity of 310,000 mph (500,000 km/h) relative to the sun.

RELATED: 2018 Space Calendar:

33 PHOTOS

2018 Space Calendar

See Gallery

January 1, 2: Supermoon/Full Wolf Moon

The moon will make its closest approach to the Earth on New Year’s Day and will appear larger and brighter than usual, earning it the distinction of ‘Supermoon.’

Additionally, the first full moon of any year earns itself the distinction ‘Full Wolf Moon.’ The term was created by Native Americans as a nod to the howling wolves they would often hear outside their villages in January.

Photo: Matt Cardy/Getty Images

January 3, 4: Quadrantids Meteor shower

The Quadrantid meteor shower, known to produce from 50-100 meteors during its peak, is 2018’s first major meteor shower.

Sadly, the light from the nearly full moon will block out most of the show.

Photo: NurPhoto/NurPhoto via Getty Images

January 31: Total Lunar Eclipse/Blue Moon

A Blue Moon is the term for the second full moon in a month with more than one full moon.

January’s Blue Moon also happens to coincide with a total lunar eclipse.

Photo: REUTERS/Mike Hutchings

February 15: Partial Solar Eclipse

This type of solar eclipse occurs when the moon casts a shadow that only covers part of the Sun.

The partial solar eclipse on Feb. 15 will only be visible in parts of South America and Antarctica. Those who wish to take it in will need to wear special protective eyewear.

Photo: REUTERS/Tatyana Makeyeva TPX IMAGES OF THE DAY

March 2: Full Worm Moon

Another term coined by Native Americans, a ‘Full Worm Moon’ is the distinction given to the first full moon in March.

As the temperature gets warmer, the ground begins to soften and earthworms begin to rear their heads through the soil again.

Photo: NICHOLAS KAMM/AFP/Getty Images

March 15: Mercury Reaches Greatest Eastern Elongation

Mercury will reach its greatest eastern elongation from the sun (i.e. its highest point above the horizon) on March 15.

This will make the planet more visible than usual.

Photo: The Royal Observatory Greenwich, London

April 22, 23: Lyrid Meteor Shower

The Lyrid meteor shower, which usually produces around 20 meteors per hour, will reach its peak between the night of April 22 and the morning of the 23rd.

Photo: Ye Aung Thu/AFP/Getty Images

‘Full Pink Moon’ is another term believed to have been coined by Native American tribes.

In April, the weather finally starts to get warmer and flowers begin to appear, earning the month’s full moon its pretty name.

Photo: Ben Birchall/PA Images via Getty Images

May 6, 7: Eta Aquarid Meteor Shower

The Eta Aquarids meteor shower, made up of dust particles left behind by Halley’s Comet, can produce up to 60 meteors per hour at its peak.

Although most of its activity can be observed in the Southern Hemisphere, northerners can still take in the show if weather conditions permit.

Photo: NASA

May 9: Jupiter Reaches Opposition

The gas giant will make its closest approach to Earth on May 9, making it appear brighter than any other time of the year.

Photo: Universal History Archive via Getty Images

May 29: Full Flower Moon

The May full moon was given this name by Native American tribes as the beginning of the month is typically when flowers are in full bloom.

Photo: REUTERS/Navesh Chitrakar TPX IMAGES OF THE DAY

June 27: Saturn Reaches Opposition

Saturn will make its closest approach to Earth on June 27, making it appear brighter than any other time of the year.

Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute/Handout via REUTERS

Jun 28: Full Strawberry Moon

As the last full moon of spring, stargazers can expect this one to be big and bright — but contrary to its name, it is not red.

Strawberry picking season reaches its peak in June, earning the month’s first full moon its delicious name.

Photo: Matt Cardy/Getty Images

July 13: Partial Solar Eclipse

This type of solar eclipse occurs when the Moon casts a shadow that only covers part of the Sun.

The partial solar eclipse on July 13 will only be visible in parts of southern Australia and Antarctica. Those who wish to take it in will need to wear special protective eyewear.

Photo: REUTERS/Mal Langsdon TPX IMAGES OF THE DAY

July 27: Mars Reaches Opposition

You guessed it — Mars will make its closest approach to Earth on July 27, making it appear brighter, and thus more visible, than any other time of the year.

Photo: NASA/Handout via Reuters

July 27: Full Buck Moon

The July full moon was dubbed the ‘Full Buck Moon’ by Native American tribes, as it appears during this time of year when male deer begin to grow their new antlers.

Photo: REUTERS/Carlo Allegri

July 28, 29: Total Lunar Eclipse

A total lunar eclipse occurs when the moon pbades completely through the Earth’s shadow, lending the moon a dark-redish appearance.

July’s lunar eclipse will be visible in North America, eastern Asia and Australia.

Photo: REUTERS/Kacper Pempel

August 11: Partial Solar Eclipse

This type of solar eclipse occurs when the moon casts a shadow that only covers part of the Sun.

The partial solar eclipse on Aug. 11 will only be visible in parts of Canada, Greenland, northern Europe, and northern and eastern Asia. Those who wish to take it in will need to wear special protective eyewear.

Photo: REUTERS/Samrang Pring TPX IMAGES OF THE DAY

August 12, 13: Perseid Meteor Shower

The Perseids meteor shower, made up of dust particles left behind by the Swift-Tuttle Comet, can produce up to 60 meteors per hour at its peak.

The thin crescent moon on the night of Aug. 12 will create favorable viewing conditions for the celestial spectacle, which should be visible all over the world.

Photo: REUTERS/Paul Hanna

August 17: Venus Reaches Greatest Eastern Elongation

Venus will make its closest approach to Earth on Aug. 17, making it appear brighter, and thus more visible, than any other time of the year.

Photo: Photo12/UIG via Getty Images

August 26: Full Sturgeon Moon

The August full moon earned this distinction from Native American tribes, as sturgeon were most readily caught during this month.

Photo: Pradita Utana/NurPhoto via Getty Images

September 7: Neptune Reaches Opposition

Neptune will make its closest approach to Earth on Sept. 7, making it appear brighter, and thus more visible, than any other time of the year.

However, due to its distance from Earth, the blue planet will only appear as a small dot to even those using telescopes.

Photo: Time Life Pictures/NASA/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

September 24, 25: Full Harvest Moon

The name ‘Harvest Moon’ goes to the full moon that occurs closest to the autumn equinox every year.

Photo: Santiago Vidal/LatinContent/Getty Images

October 8: Draconid Meteor Shower

The Draconid meteor shower, which is made up of dust particles left behind by comet 21P Giacobini-Zinner, only produces about 10 meteors per hour at its peak.

However, the new moon on the night of Oct. 9 will create extremely favorable viewing conditions for the shower, which should be visible all over the world.

Photo: NASA

October 21, 22: Orionid Meteor Shower

Another shower produced by Halley’s comet, the Orionids will likely be at least partially blocked by the light of the nearly full moon on Oct. 21.

Photo: Yuri SmityukTASS via Getty Images

October 23: Uranus Reaches Opposition

Uranus will make its closest approach to Earth on Oct. 23, making it appear brighter, and thus more visible, than any other time of the year.

Unfortunately, it is so far away from the Earth that it will not be visible without a powerful telescope.

Photo: Time Life Pictures/Jet Propulsion Laboratory/NASA/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images

October 24: Full Hunter’s Moon

October’s full moon was dubbed the ‘Full Hunter’s Moon’ by Naive American tribes since animals are more easily spotted during this time of year after plants lose their leaves/

Photo: PA Wire/PA Images

November 5, 6: Taurids Meteor Shower

The Taurids is a small meteor shower that only produces between 5-10 meteors per hour at its peak.

Photo: NASA

November 17, 18: Leonid Meteor Shower

The Leonid meteor shower, which radiates from the constellation Leo, produces about 15 meteors per hour at its peak.

Photo: Ali Jarekji / Reuters

November 23: Full Beaver Moon

November’s full moon was given its name by Native America tribes, who would set up beaver traps during the month in hopes of catching the creatures for their warm fur.

Photo: Matt Cardy/Getty Images

December 13, 14: Geminids Meteor Shower

The Geminids meteor shower, produced by debris left behind by an asteroid known as 3200 Phaethon, is renowned as one of the most spectacular of its kind.

The show can produce up to 120 meteors per hour at its peak and will be visible all over the planet on the night of Dec. 13.

Photo: REUTERS/Navesh Chitrakar

December 21, 22: Ursids Meteor Shower

The Draconid meteor shower, which is made up of dust particles left behind by the Tuttle Comet, only produces about 10 meteors per hour at its peak.

Sadly, the full moon on Dec. 22 will likely create unfavorable viewing conditions for the smaller show.

Photo: REUTERS/Daniel Aguilar DA/LA

December 22: Full Cold Moon

Unsurprisingly, December’s full moon was named by Native American tribes after the cold, winter weather.

Photo: Matt Cardy/Getty Images

HIDE CAPTION

SHOW CAPTION

And Barnard’s Star is getting closer to us every day: In about 10,000 years, the red dwarf will take over the nearest-star mantle from the Alpha Centauri system. At that time, just 3.8 light-years will separate Barnard’s Star from the sun.

Barnard’s Star is about twice as old as Earth’s sun, one-sixth as mbadive and just 3 percent as luminous. Because Barnard’s Star is so dim, its “habitable zone” — the range of distances where liquid water may be possible on a world’s surface — lies extremely close-in. Indeed, researchers estimate that zone to be a sliver that lies 0.06 AU to 0.10 AU from the star. (One AU, or astronomical unit, is the Earth-sun distance — about 93 million miles, or 150 million kilometers.)

The habitable-zone concept is a tricky one, of course. Gauging a world’s true habitability requires a strong working knowledge of its atmospheric composition and thickness, among other characteristics. And such information is hard to come by for exoplanets.

A long search

Barnard’s Star has long been a target of exoplanet hunters, but their searches have always come up empty — until now.

And the new detection wasn’t easy: Ribas and his team badyzed huge amounts of data, both archival and newly gathered, before finally digging up Barnard’s Star b.

They used the “radial velocity” method, which looks for changes in starlight caused by the gravitational tug of an orbiting planet. Such tugs cause a star to wobble slightly, shifting its light toward red wavelengths at times and toward the blue end of the spectrum at others, as seen from Earth. [7 Ways to Discovery Alien Planets]

“We used observations from seven different instruments, spanning 20 years of measurements, making this one of the largest and most extensive datasets ever used for precise radial-velocity studies,” Ribas said in the same statement. “The combination of all data led to a total of 771 measurements — a huge amount of information!”

Never before had the radial velocity method been used to find such a small planet in such a distant orbit, study team members said. (Big, close-in planets tug their host stars more powerfully and therefore cause more dramatic, and more easily detectable, light shifts.)

Those seven instruments were the High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS), at the European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) La Silla Observatory in Chile; the Ultraviolet and Visual Echelle Spectrograph on the Very Large Telescope, at ESO’s Parbad Observatory in Chile; HARPS-North, at the Galileo National Telescope in the Canary Islands; the High Resolution Echelle Spectrometer, at the Keck 10-meter telescope in Hawaii; the Carnegie Institute’s Planet Finder Spectrograph, at the Magellan 6.5-m telescope at Las Campanas Observatory in Chile; the Automated Planet Finder at the 2.4-m telescope at the University of California’s Lick Observatory; and& CARMENES, at the Calar Alto Observatory in Spain.

The researchers also detected hints of another possible planet in the system, orbiting farther out than Barnard’s Star b — way farther out, with an orbital period of 6,600 Earth days. But this second signal is too weak to be deemed a planet candidate, Teske said.

“There’s not enough data,” she told Space.com.

A frigid super-Earth

Barnard’s Star b is at least 3.2 times more mbadive than our own planet, making it a “super-Earth” — the clbad of worlds that are significantly larger than Earth but smaller than “ice giants” such as Neptune and Uranus.

The newfound planet candidate lies 0.4 AU from its host star and completes one orbit every 233 Earth days, according to the new study.

This orbital distance is similar to that of radiation-blasted Mercury in our own solar system. But, because Barnard’s Star is so dim, the potential planet lies right around the system’s “snow line” — the region where volatile materials such as water can condense into solid ices.

“Until now, only giant planets had been detected at such a distance from their stars,” Rodrigo Diaz, of the Institute of Astronomy and Space Physics at the National Council of Scientific and Technical Research and the University of Buenos Aires in Argentina, said in an accompanying “News and Views” article that was also published today in Nature.

“The authors’ discovery of a low-mbad planet near the snow line places strong constraints on formation models for this type of planet,” added Diaz, who was not involved in the new study.

Barnard’s Star b, if it does indeed exist, is not a very promising abode for life as we know it, at least not on the surface. The potential planet is likely very cold, with an estimated surface temperature of about minus 275 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 170 degrees Fahrenheit), study team members said.

Confirmation of Barnard’s Star b is unlikely to come from additional radial-velocity measurements, Diaz wrote. But super-precise measurements of star positions, such as those now being made by the European Space Agency’s Gaia spacecraft, may do the job in the next few years, he added.

“Even more excitingly, the next generation of ground-based instrumentation, also coming into operation in the 2020s, should be able to directly image the reported planet, and measure its light spectrum,” Diaz wrote.

“Using this spectrum, the characteristics of the planet’s atmosphere — such as its winds and rotation rate — could be inferred,” he added. “This remarkable planet therefore gives us a key piece in the puzzle of planetary formation and evolution, and might be among the first low-mbad exoplanets whose atmospheres are probed in detail.”

WANT MORE STORIES ABOUT EXOPLANETS?

FOLLOW NBC NEWS MACH ON TWITTER, FACEBOOK, AND INSTAGRAM.

[ad_2]

Source link